Hotel companies are service professionals and complex organizations comprising members of an organization (Agag & Eid, 2019). Hotel employees often have poor working conditions, such as insufficient education, training, compensation, long working hours, and excessive workloads, as well as limited career and promotion opportunities (Karatepe et al., 2009; Kusluvan et al., 2010). In other words, hotel companies have limited resources and few positions available within the organization. Therefore, members of this type of organization understand political action as a naturally occurring phenomenon and an option to influence decision making (Poon, 2003).

In the case of hotels, the political behavior of employees is natural and routine, despite causing uncertainty, disagreement, and conflicts among employees (Chen et al., 2022). Hotel managers pursuing the integration of the entire organization and political behavior within a dysfunctional organization are significant obstacles to achieving goals (Yang, 2017). In the context of hotel organizational politics, members of the organization directly or indirectly affect other members through their actions or through informal, unapproved norms that sit outside formal standardized procedures to achieve individual or group purposes (Witt et al., 2000). Employees recognize this as a job-stress factor (Karatepe, 2013). Organizational politics within a company or hotel team can decrease trust in the organization and one’s position, and leads to mutual contempt and conflict among members, along with poor job performance (Aryee et al., 2004).

Organizational politics may result in critical attitudes, such as indifference, negative feelings, or distrust of the organization’s policies, systems, changes, and innovation (Aryee et al., 2004). For sustainable growth of hotels, fair organizational management is needed to make employees feel satisfied as members of social exchange relationships; this will help to stimulate a desire to contribute to improving the organization’s performance (Nadiri & Tanova, 2010). As a participant in an exchange relationship who invests personal effort in the work of a hotel organization with an expectation of reward, employees are constantly evaluating and responding to whether the process of deriving results is fair and whether the compensation or responsibility they deserve is higher or lower than what they have been given (Turner, 2007). As such, employees in unfair arrangements within hotel organizations may refrain from expressing their opinions to protect and maintain their own safety and express their dissatisfaction (Lee et al., 2023; Morrison & Milliken, 2000).

In the situation of organizational silence, where there is an environment of insufficient trust, accurate information and opinions about the problems of hotel companies’ organizations are not revealed, which can be a major obstacle to achieving organizational goals (Dimitris & Vakola, 2007). The actions of a hotel employee are crucial in maintaining internal cooperation. Uncooperative performance while carrying out work duties can lead to knowledge concealment (Chen et al., 2022). Knowledge-hiding behavior represents an individual’s intention to conceal or withhold information requested by others (Chiu et al., 2006; Collins & Smith, 2006; Connelly et al., 2012). Intentionally concealing knowledge that is not shared in time due to indifference to customer service and cynical behavior of hotel organizations leads to employee turnover, as well as denying organizational innovation, creativity, interdependent collaboration, and mutual trust among colleagues (Shi et al., 2021; Zibenberg, 2021). The perception of unfairness in hotel organizations is related to the entire organization, meaning it is not simply a problem of performance decline and motivation at the individual level (Howard & Cordes, 2010).

Despite the importance of the perception of organizational politics, organizational injustice, organizational silence, and hotel knowledge-hiding behavior, studies of the relationships between these variables are few in number. This study sought to verify the relationships between these variables in the hotel setting. Our goal was to clarify the importance of organizational and political perceptions that can positively affect hotel jobs and organizations, thus providing academic and practical implications for maximizing the efficiency of hotel human resource management.

Organizational politics perception is the perception of political tendencies in an organization made up of individuals (Lee et al., 2023). This perception is subjective, reflecting the personal experience of an individual in terms of conflict avoidance and promotion compensation policy. Conflict avoidance refers to the perception of the degree to which members of an organization refrain from engaging in intentional behavior for private interests (Lee et al., 2023). Promotion compensation policy refers to the degree to which individual members of the organization perceive that the results of promotion or compensation are determined by political influence (Kacmar & Carlson, 1997).

The greater the perception of organizational politics by members of the organization, the more they perceive that the distribution of results, such as promotions and wages, is due to organizational politics and is made unfair by the political structure (Andrews & Kacmar, 2001). Conflicts between employees are also natural phenomena that exist in all organizations, and they may arise due to inconsistencies in values and goals, such as employees’ differing interests, preferences, and opinions on how to achieve goals (Rahim, 2002). Many studies have found that the perception of organizational politics affects distributive and procedural injustice (Kaya et al., 2016; Miller & Nicols, 2008). An atmosphere of conflict avoidance and the promotion of compensation policies, which are perceptions of organizational politics, directly affect distributive, procedural, and interaction fairness (Andrews & Kacmar, 2001; Kaya et al., 2016; Miller & Nicols, 2008; Rahim, 2002). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The perception of organizational politics will have a positive relationship with organizational injustice.

Organizational injustice comprises distributive, procedural, and interactional injustice types, which are opposing concepts of organizational justice (Colquitt et al., 2005). Distributive justice refers to the degree to which members of an organization expect corresponding compensation based on their efforts. When employees experience unfair treatment, they may respond with negative behaviors like theft or destruction in an effort to restore fairness (Colquitt et al., 2005; Homans, 1961). Procedural justice refers to the perceived fairness of an organization by employees regarding the right to speak, which may require rules, procedures, and opportunities to participate, in order to determine compensation allocations. Repeated unfair treatment has been shown to cause a decrease in creative ability (Alexander & Ruderman, 1987; Streicher et al., 2012). Interactional justice refers to the quality of personal treatment shown by decision makers in the process of implementing procedures, such as respect for rights, exclusion of prejudice, displays of kindness, respect for opinions, explanations of the decision-making process, and the fairness of personal treatment perceived by employees (Akhbari et al., 2013; Bies, 1986).

The silence of employees can be said to be a continuous behavior that responds to various personal and situational factors under unfair circumstances (Pinder & Harlos, 2001). Organizational silence by employees reflects the realization that there will be no change even if an improvement plan is presented owing to unfair organizational situations, or that there will be disadvantages in threatening organizational situations (Van Dyne et al., 2003). Among the components of organizational silence are acquiescent silence and defensive silence (Milliken & Morrison, 2003). Acquiescent silence refers to silence caused by a lack of willingness to engage in the current situation due to submission and acquiescence (Van Dyne et al., 2003). In contrast, defensive silence refers to self-protective silence used to avoid negative experiences due to expressing opinions (Van Dyne et al., 2003). It has been posited that the silence of employees has a negative relationship with the individual’s perception of organizational fairness (Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008). Organizational silence among employees can result from negative feedback from superiors and it negatively affects organizational decision making and the change process (Ghasemi et al., 2016). Distributive fairness, procedural fairness, and interactive fairness directly affect acquiescent silence and defensive silence, which employees perceive as organizational injustice (Ghasemi et al., 2016; Morrison & Milliken, 2000; Pinder & Harlos, 2001; Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008; Van Dyne et al., 2003). Therefore, this study established the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Organizational injustice will have a positive relationship with organizational silence.

Organizational injustice represents the mechanisms of the perception of unjust treatment of members of the organization, hostile behavior of individuals, and unfair distribution, procedures, and information that lead to negative behaviors such as noncompliance, avoidance of participation, and risk taking (Hystad et al., 2014). Employees have reported that an unfair environment of knowledge management increases individual knowledge concealment (Abubakar et al., 2019). Organizational support to strengthen knowledge-management fairness among employees lowers knowledge concealment (Oubrich et al., 2021). The relational conflict between groups within the organization and employees is linked to a competition-based atmosphere, which increases individuals’ knowledge concealment (Peng et al., 2021). When their relationship with the exchange target is hostile, individuals curb knowledge sharing (Peng et al., 2021). In the end, the organizational injustices of distributive, procedural, and interactional injustice affect knowledge-hiding behaviors (Abubakar et al., 2019; Hystad et al., 2014; Oubrich et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021). Therefore, this study established the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Organizational injustice will have a positive relationship with knowledge-hiding behavior.

Knowledge-hiding behavior comprises staying silent, evasive hiding, and rationalized hiding (Connelly et al., 2012). Playing dumb and evasive hiding are intentional hiding behaviors of information providers, and rationalized hiding refers to the intention to deceive. This includes cases where it is difficult to provide information. Playing dumb refers to intentionally pretending not to know information when asked for expertise from other members (Connelly et al., 2012). Evasive hiding refers to intentionally providing inaccurate information or providing information that may lead to incorrect results (Connelly et al., 2012). Rationalized hiding refers to not providing information for confidentiality reasons or when it is difficult to provide information due to requests from superiors or other organizations as it may disadvantage the employee, for example, from being promoted (Connelly et al., 2012).

Organizational silence and knowledge concealment by members of an organization can be explained using conservation of resources theory. Silence behavior is the strategic and intentional act of choosing a defensive attitude to prevent more loss or preserve remaining resources (Ng & Feldman, 2012). When threats occur, which may cause a loss of resources (Ng & Feldman, 2012), the silence of employees prevents the transfer of essential source knowledge to other members because silencing hinders knowledge transfer (Bogosian & Stefanchin, 2018). Distrust and lack of reciprocity in organizations promotes knowledge concealment (Jha & Varkley, 2018). Similarly, organizational silence and knowledge are influenced by behaviors because they begin with the motivation to maintain the competitive advantage and value of existence within an organization by maintaining the knowledge of its employees (Bartol & Srivastava, 2002). Acquiescent and defensive silence directly affect knowledge-hiding behaviors such as playing dumb, evasive hiding, and rationalized hiding (Bartol & Srivastava, 2002; Bogosian & Stefanchin, 2018; Jha & Varkley, 2018; Ng & Feldman, 2012). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Organizational silence will have a positive relationship with knowledge-hiding behavior.

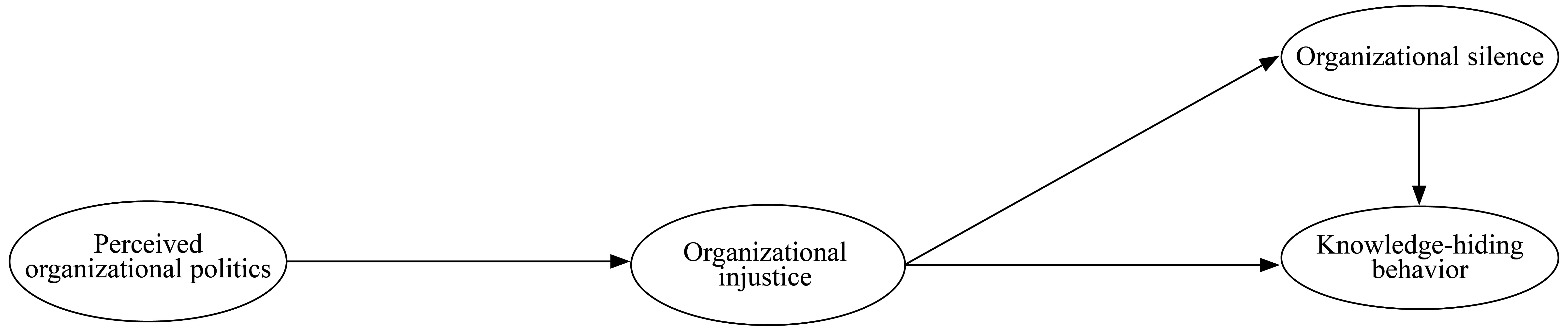

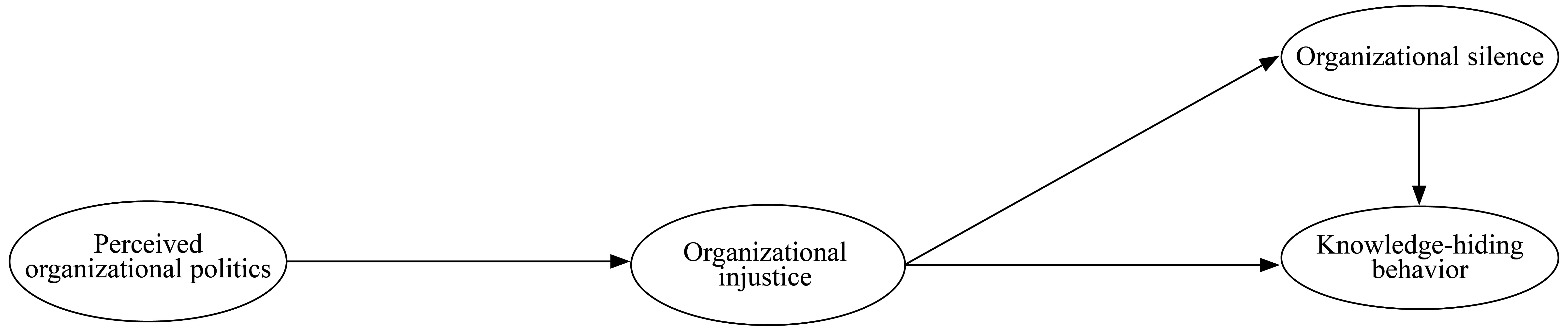

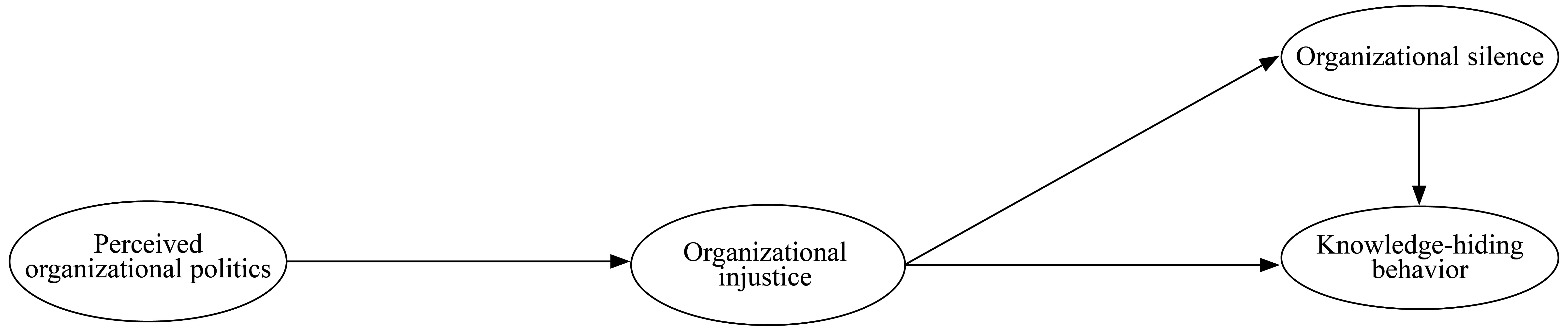

The research model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical Model

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample of this study comprised 344 employees working at hotels in South Korea in 2023. We collected data using a snowball sampling approach during July 2023. Ethical approval was not required, as we conducted an anonymous online survey. Data were collected with the voluntary participation and informed consent of respondents.

Measures

We adopted items from previous organizational and human resource management studies. We translated all items into Korean then back to English and verified the comprehensibility of the content in consultation with hoteliers. Items were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

We measured the perception of organizational politics by measuring conflict avoidance atmosphere (four items, e.g., “There is a powerful group in our hotel that exerts absolute influence”) and promotion compensation policy (four items, e.g., “In our hotel, there have been political decisions related to promotions, compensation, and positioning”) from Kacmar and Carlson (1997).

We measured organizational injustice by five items from Colquitt (2001) assessing distributive injustice (e.g., “The level at which I am being compensated with wages is not fair”), four items from Niehoff and Moorman (1993) assessing procedural injustice (e.g., “The procedure that the hotel uses for decision making is not fair”), and four items from Rupp and Cropanzano (2002) assessing interactional injustice (e.g., “My boss does not consider my opinion”).

Organizational silence was assessed with eight items from Van Dyne et al. (2003), four of which measured acquiescent silence (e.g., “I don’t want to be very involved in the hotel, so I don’t present ideas that can change things”), and four of which measured defensive silence (e.g., “I don’t talk about my thoughts to others because I’m worried that the results will be bad”).

We measured knowledge-hiding behavior with 10 items from Connelly et al. (2012). The dimension of evasive hiding comprised three items (e.g., “I said I would let you know about the knowledge and information requested by my colleague”), playing dumb comprised three items (e.g., “I pretended not to know about the knowledge and information requested by my colleague”), and rationalized hiding comprised four items (e.g., “I explained that I wanted to provide information, but I couldn’t because of the situation”).

Data Analysis

We analyzed the collected data using SPSS 27.0 and Amos 27.0. We used a two-step approach, conducting confirmatory factor and reliability analyses to verify the validity and reliability of the measured variables. Subsequently, we conducted structural equation modeling to verify the hypotheses.

Results

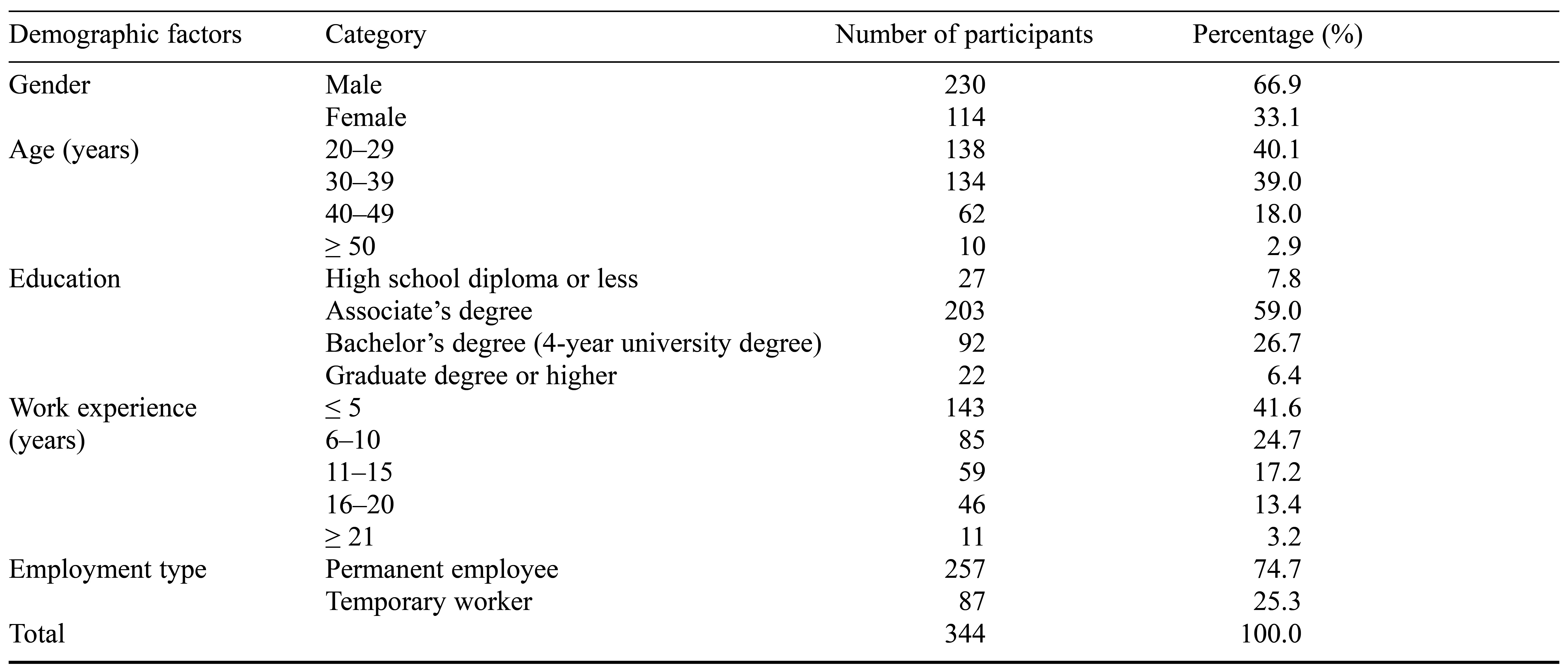

Demographic Details of the Respondents

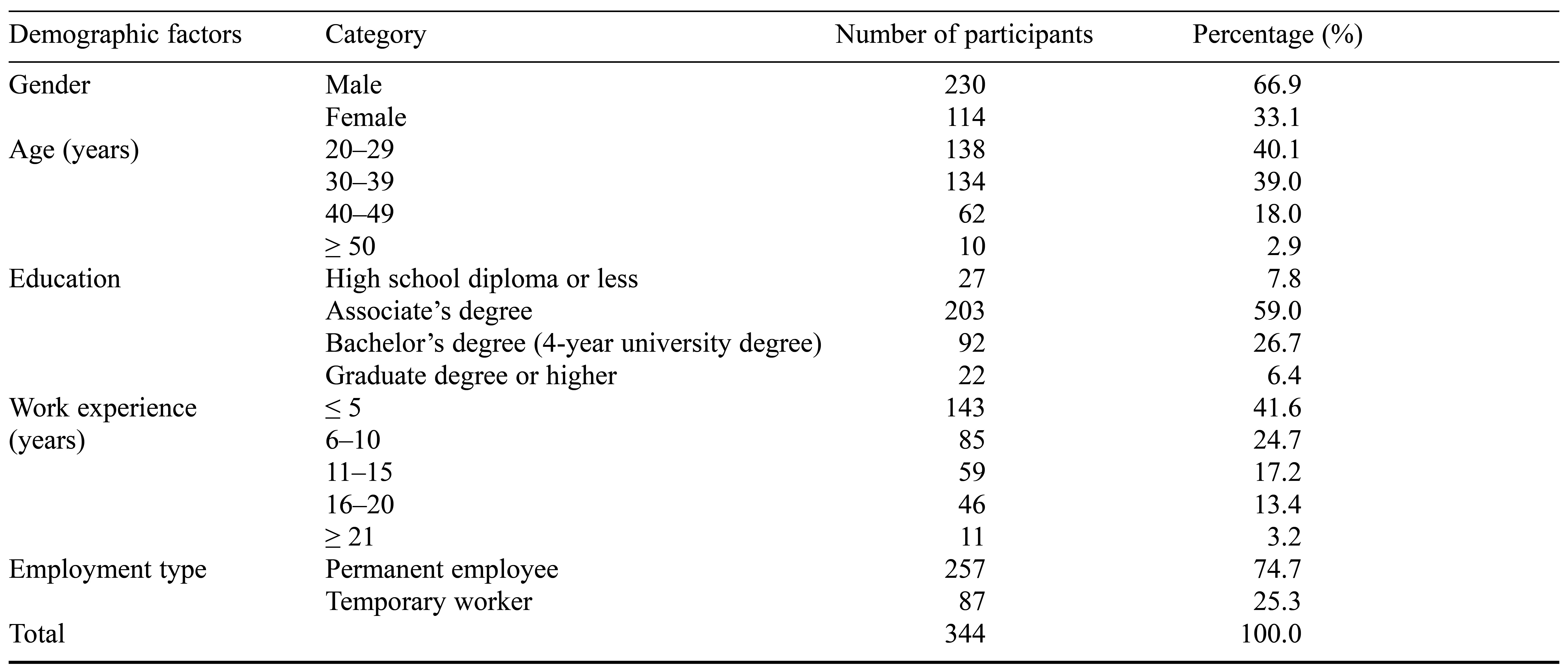

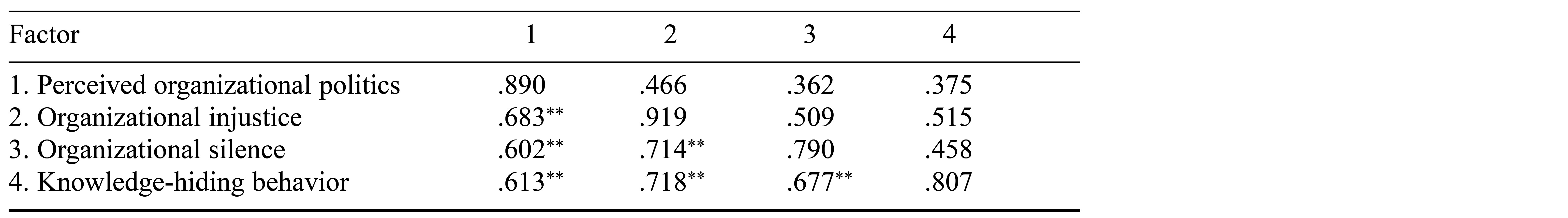

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1. Respondents’ Demographic Profile

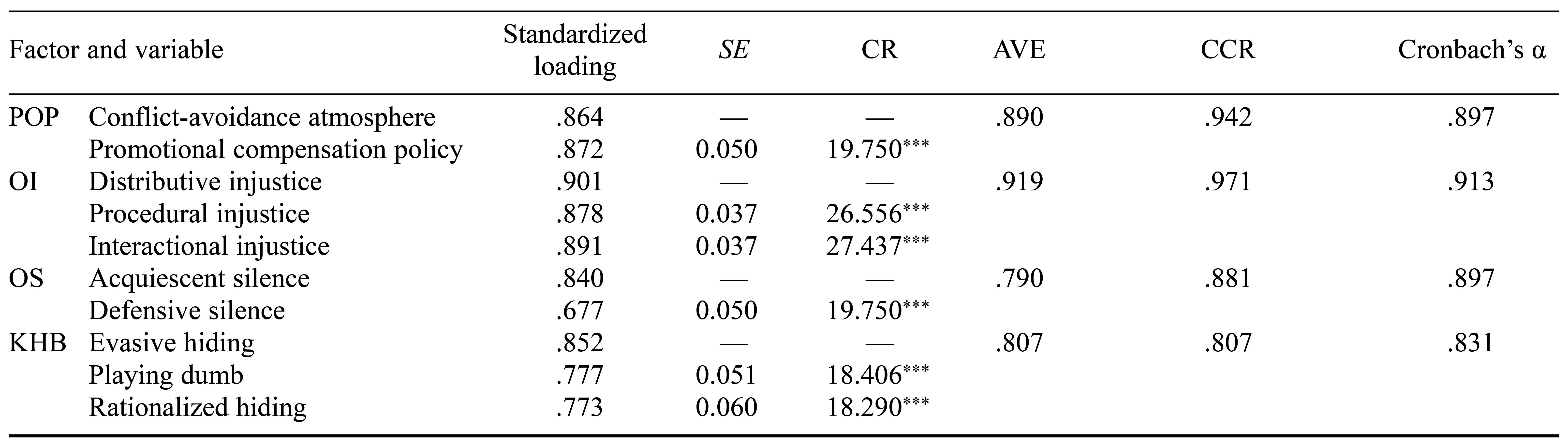

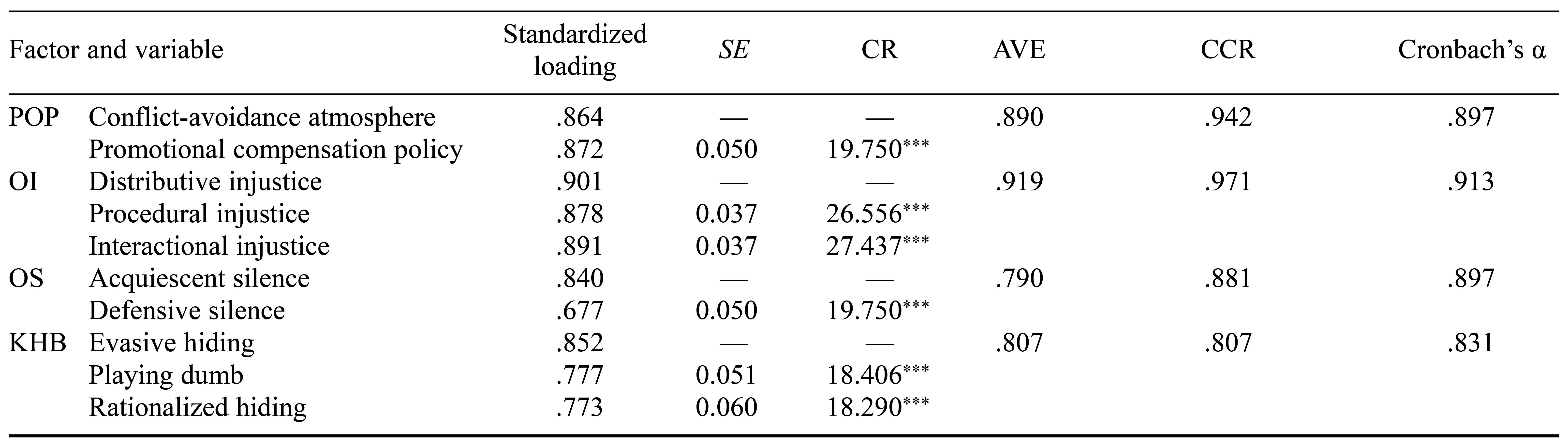

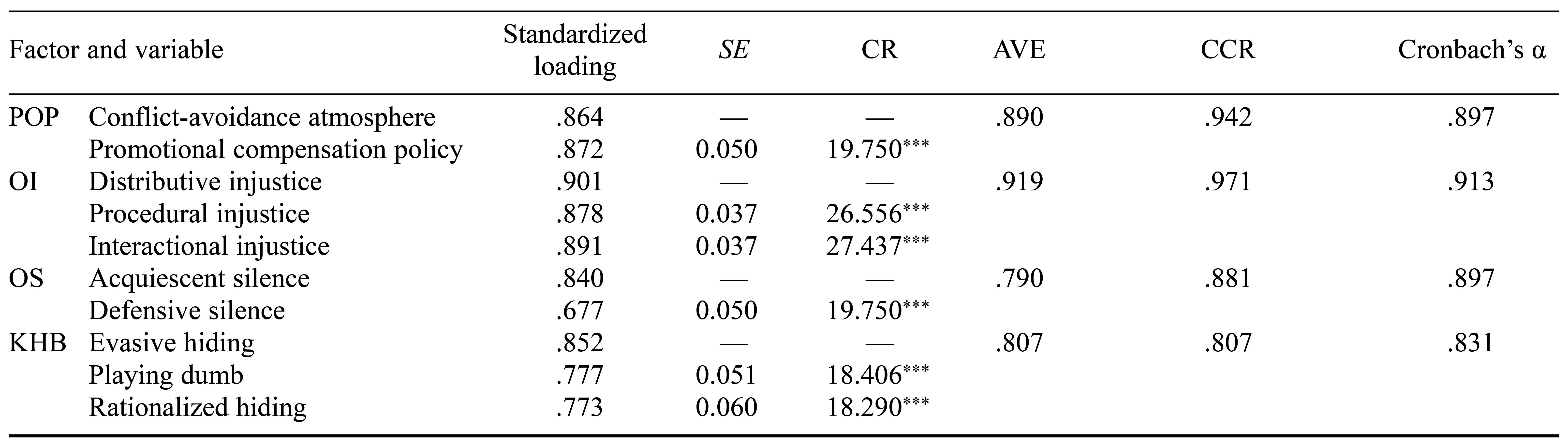

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The confirmatory factor analysis results are presented in Table 2. We measured the dimensions of each concept composed of secondary factors with primary factors according to the mean scores using a multidimensional parceling approach. The results indicated a suitable fit of the four-factor model to the data (i.e., perceived organizational politics, organizational injustice, organizational silence, and knowledge-hiding behavior), χ² = 91.359 (df = 29, p < .001), minimum discrepancy (CMIN/df) = 3.150, root-mean-square residual (RMR) = .010, goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = .958, adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) = .920, normed fit index (NFI) = .971, incremental fit index (IFI) = .980, TLI Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .969, comparative fit index (CFI) = .980, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .071. In addition, the standardized factor loadings were greater than .50, and the composite reliability was statistically significant (≥ .70; Hair et al., 2013). Cronbach’s alpha values ranged between .86 and .93, which according to Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) indicates the scales were reliable.

Table 2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results

Note. POP = perceived organizational politics; OI = organization injustice; OS = organizational silence; KHB = knowledge-hiding behavior; CR = critical value; AVE = average variance extracted; CCR = composite construction reliability.

*** p < .001.

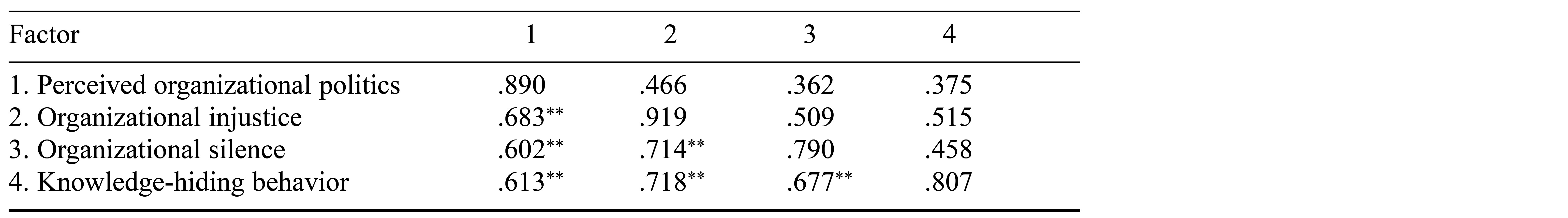

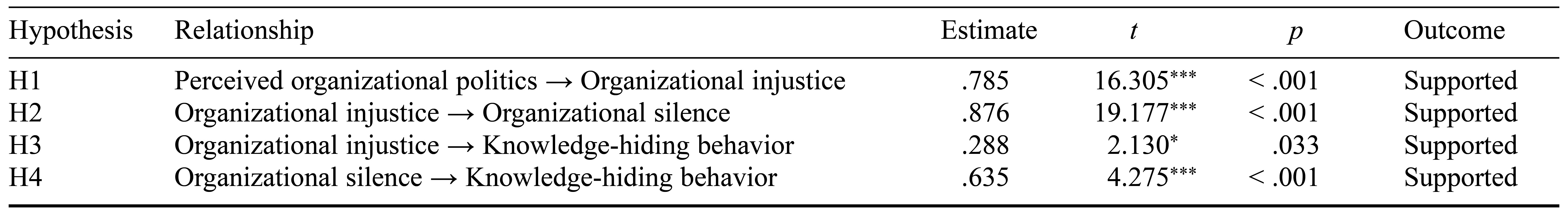

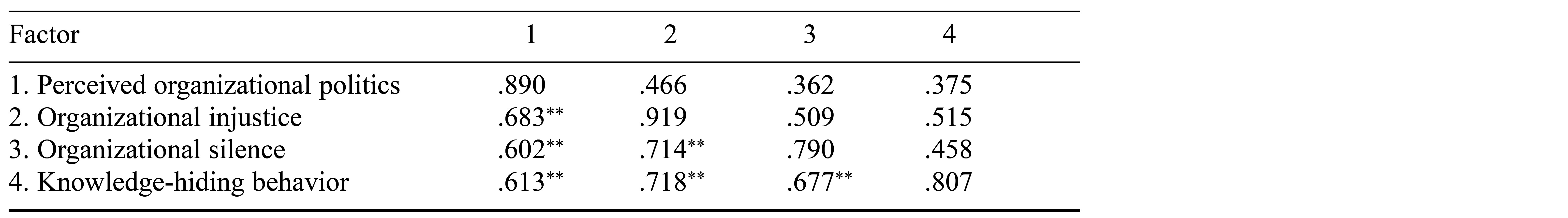

Discriminant Validity

Table 3 shows the discriminant validity of the measures. The average variance extracted (AVE) values of the variables were larger than the square of the correlation coefficient and were greater than .515; therefore, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981), the measures had acceptable discriminant validity.

Table 3. Discriminant Validity

Note. Values on the diagonal represent average variance extracted. Below the diagonal are correlation coefficients for the constructs. The area above the diagonal represents the square of correlation coefficients.

** p < .01.

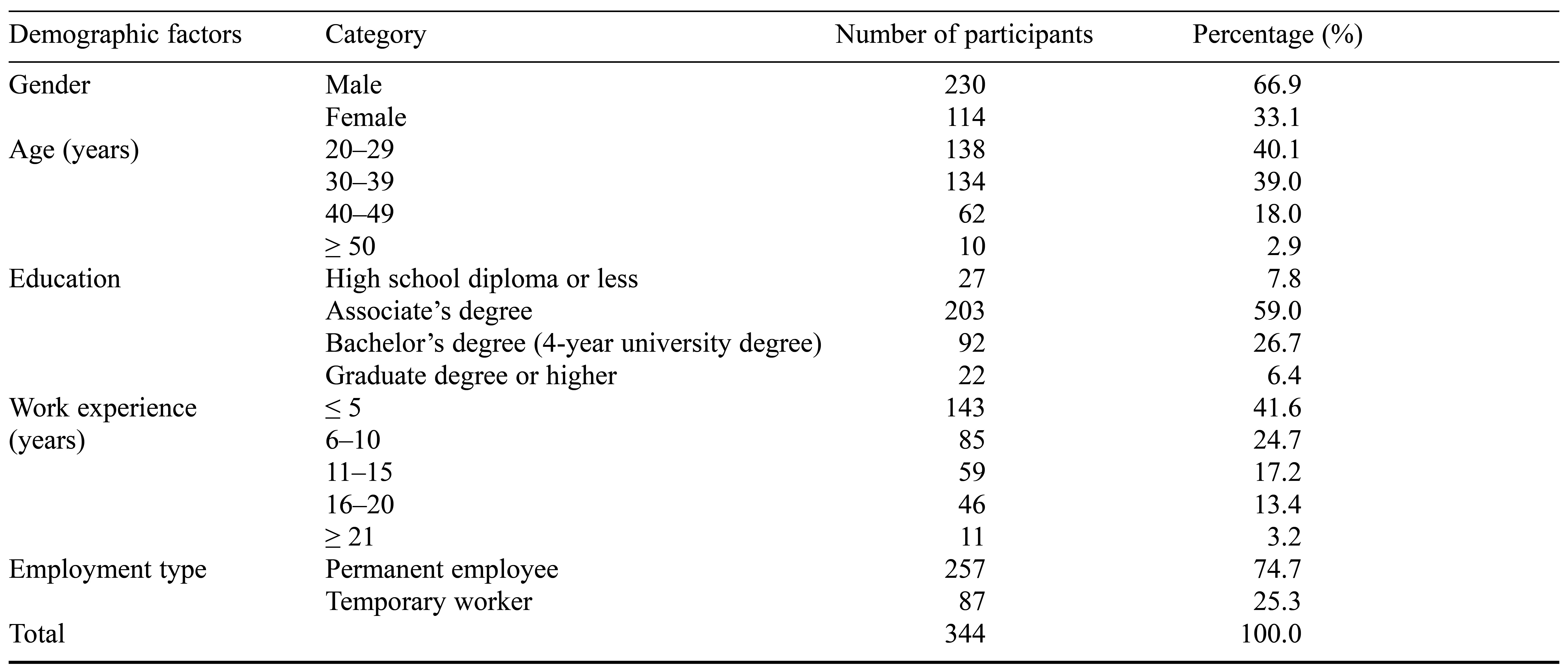

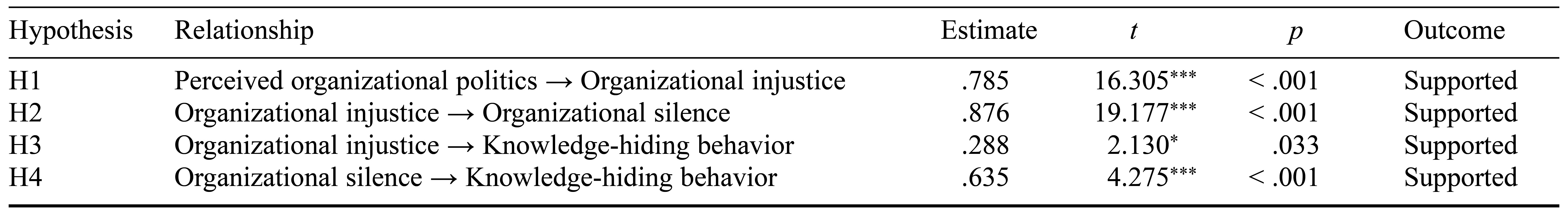

Hypothesis Testing

We performed structural equation modeling using Amos 27.0 to test the hypothesis. The model fit was acceptable (Hair et al., 2016), χ² = 102.758 (df = 31, p < .000), CMIN/df = 3.315, RMR = .013, GFI = .953, AGFI = .916, NFI = .967, IFI = .977, TLI = .966, CFI = .977, RMSEA = .073.

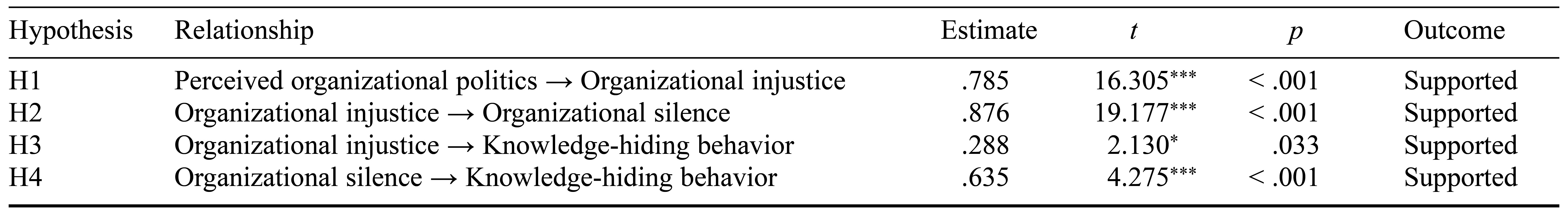

Table 4 presents the results of hypothesis testing. Perceived organizational politics was a significant positive predictor of organizational injustice; thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Organizational injustice was a significant positive predictor of organizational silence; thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Organizational injustice was a significant positive predictor of knowledge-hiding behavior; thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported. Finally, organizational silence was a significant positive predictor of knowledge-hiding behavior; thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Table 4. Result of Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

Note. * p < .05. *** p < .001.

Discussion

We conducted this study to provide data for the management and development of hotels through examining the impact of perceived organizational politics by employees on organizational injustice, along with the relationships between organizational injustice, organizational silence, and knowledge-hiding behavior. Supporting Hypothesis 1, we found that perceived organizational politics had a positive relationship with organizational injustice. This is in line with the findings of previous studies (Andrews & Kacmar, 2001; Kaya et al., 2016; Miller & Nicols, 2008; Rahim, 2002) and emphasizes the need to reduce negative organizational culture by highlighting positive organizational politics and recognizing the need for human resource management at the organizational level. Respect between organizations and individuals, a friendly atmosphere of conflict avoidance, and a promotion-compensation policy should form the basis of job performance of hotels and organizational members, thus resolving the distributive, procedural, and interactional justice perceptions of employees.

Supporting Hypothesis 2, we found that organizational injustice as perceived by hotel members had a direct effect on organizational silence. This supports previous study findings (Ghasemi et al., 2016; Morrison & Milliken, 2000; Pinder & Harlos, 2001; Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008; Van Dyne et al., 2003). Organizational injustice is the primary factor influencing communication between organizations and individuals, which is the basis for employee job performance.

Supporting Hypothesis 3, organizational injustice perceived by hotel members had a direct effect on knowledge-hiding behavior. This is consistent with the results of previous studies (Abubakar et al., 2019; Hystad et al., 2014; Oubrich et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021). These results indicate that allowing individuals to smoothly share their knowledge in the case of hotels with relatively high human dependence will help the company to secure a competitive advantage. To solve the problem of distributive, procedural, and interactional injustice in the hotel organization, it is necessary to create a supportive organizational culture so that management can share their own knowledge and reduce the perception that it undermines the organization’s justice.

Supporting Hypothesis 4, we found that organizational silence had a direct effect on knowledge-hiding behavior. This supports previous study findings (Bartol & Srivastava, 2002; Bogosian & Stefanchin, 2018; Jha & Varkley, 2018; Ng & Feldman, 2012). Management of these issues is necessary as the acquiescent and defensive silence of individuals emerging from organizational silence can lead to them playing dumb and engaging in evasive and rationalized hiding, which are aspects of knowledge-concealment behavior.

Theoretical Implications

Our findings have several theoretical implications for human resource management of hotel employees who are highly dependent on other industries. Unlike previous studies that focused on the psychology of members of the entire hotel, we explored the effect of perceived organizational politics by hotel employees in a highly competitive environment. Our research contributes to human resource management theory, as no previous studies have examined the relationships between perceived organizational politics and organizational injustice, organizational silence, and knowledge-hiding behavior. Individual perceptions of organizational politics were found to affect organizational injustice and organizational behavior (Andrews & Kacmar, 2001). People sensitive to organizational political perceptions are more susceptible to organizational injustice, leading to organizational silence and knowledge-hiding behavior (Hystad et al., 2014; Morrison & Milliken, 2000; Ng & Feldman, 2012). Reducing organizational injustice is an effective way to reduce organizational silence and knowledge-hiding behavior (Abubakar et al., 2019; Pinder & Harlos, 2001), and employees are likely to actively participate in sharing knowledge while expressing their opinions when they feel they are being treated fairly (Oubrich et al., 2021; Van Dyne et al., 2003). As creating a culture of silence within an organization increases the knowledge-hiding behavior of employees (Bogosian & Stefanchin, 2018), creating an environment where they can freely express their opinions helps improve organizational effectiveness while activating knowledge sharing (Jha & Varkkey, 2018). Our findings are significant in the theory of human resource management, which comprehensively reviews various aspects of experiences in a highly competitive workplace era to explain hotel working environments and how to promote innovation.

Practical Implications

There are also practical implications of our findings. It is necessary to develop cooperation and trust between hotels and employees by regulating behaviors and roles based on environmental changes in the hotel industry and easing perceived organizational politics. We suggest that perceived organizational politics leads to organizational injustice among the members of an organization, leading to organizational silence and knowledge-hiding behavior, which can degrade job performance. Improvement of the organizational culture would help to alleviate this (Bartol & Srivastava, 2002; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Peng et al., 2021; Tangirala & Ramanujam, 2008). It is essential to create an organizational culture in which hotel members can freely express their opinions (Taylor & Wright, 2004). Hotel companies’ managers and leaders should encourage the sharing of knowledge among members of the organization and prevent knowledge-hiding behavior (Bock et al., 2005). In addition, hotels are highly dependent on human resources, and the job-performance capabilities of members of the organization, which are intangible assets, have a significant influence on customers; thus, effective communication is needed to build trust (Aryee et al., 2004). A conflict-avoidance atmosphere and promotion-compensation policies should be implemented to create a warm organizational culture (Turner, 2007). Through human resource management tasks, managers can understand the impact of self-sacrificing behavior on organizational members and hotels (Nadiri & Tanova, 2010). However, a hotel’s excessive intervention in organizational politics can negatively affect managers and hotel organizations (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Unprepared interventions in organizational politics to enhance managers’ and employees’ job-performance capabilities will not achieve good job and organizational performance. In addition, a hotel’s excessive organizational culture may negatively affect managers’ roles, pride, and identity (Lee et al., 2023). Thus, it is necessary to properly harmonize personnel management centered on effective communication and the interests of the organization’s members and managers (Lee et al., 2003).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The limitations of this study are as follows: First, there may be differences in the impact of the observed relationships depending on the size of the hotel and the types of perceived organizational politics, organizational injustice, organizational silence, and knowledge-hiding behaviors. This includes tourism companies in areas where the scale of these variables has not been measured. Thus, it is necessary to investigate how perceived organizational politics, organizational injustice, organizational silence, and knowledge-hiding behaviors in hotels affect the outcome variables and how the effects differ by type of organization. Second, our study was conducted only with hotel employees. Since the management type and total number of workers may differ for each hotel grade, perceptions of organizational politics by employees may differ. Therefore, it is necessary to measure perceived organizational politics according to various hotel environments. Third, this study had a cross-sectional design, which is widely used in various fields of social science, but it has limitations, such as difficulty in establishing cause-and-effect relationships, the possibility of selection bias, and difficulty in tracking changes over time. Finally, this study used the snowball-sampling technique, which introduces limitations such as the possibility of a lack of representativeness, selection bias, cost considerations, and time consumption. Future studies could introduce alternative sampling techniques to increase the generalizability of the research results.

References

Abubakar, A. M., Behravesh, E., Rezapouraghdam, H., & Yildiz, S. B. (2019). Applying artificial intelligence technique to predict knowledge hiding behavior. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 45–57.

Agag, G., & Eid, R. (2019). Examining the antecedents and consequences of trust in the context of peer-to-peer accommodation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81, 180–192.

Akhbari, M., Tabesh, N., & Ghasemi, V. (2013). Perceived organizational justice, job satisfaction, and OCB: How do they relate to each other? Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 3(7), 512–523.

Alexander, S., & Ruderman, M. (1987). The role of procedural and distributive justice in organizational behavior. Social Justice Research, 1(2), 177–198.

Andrews, M. C., & Kacmar, K. M. (2001). Discriminating among organizational politics, justice, and support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(4), 347–366.

Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., & Budhwar, P. S. (2004). Exchange fairness and employee performance: An examination of the relationship between organizational politics and procedural justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 94(1), 1–14.

Bartol, K. M., & Srivastava, A. (2002). Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward systems. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(1), 64–76.

Bies, R. J. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. Research on Negotiation in Organizations, 1(1), 43–55.

Bock, G.-W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y.-G., & Lee, J.-N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87–111.

Bogosian, R., & Stefanchin, J. E. (2018). Employee silence is not always consent. Rutgers Business Review, 3(2), 121–138.

Chen, L., Liu, Y., Hu, S., & Zhang, S. (2022). Perception of organizational politics and innovative behavior in the workplace: The roles of knowledge-sharing hostility and mindfulness. Journal of Business Research, 145, 268–276.

Chiu, C.-M., Hsu, M.-H., & Wang, E. T. G. (2006). Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decision Support Systems, 42(3), 1872–1888.

Collins, C. J., & Smith, K. G. (2006). Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 544–560.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400.

Colquitt, J. A., Greenberg, J., & Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2005). What is organizational justice? A historical overview. In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 3–56). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., & Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(1), 64–88.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Dimitris, B., & Vakola, M. (2007). Organizational silence: A new challenge for human resource management. Athens University of Economics and Business, 6(1), 1–19.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Ghasemi, P., Zomorrodi, A., & Akbari Nasab, J. (2016). Studying the role of organizational justice, commitment and ethical climate in organizational silence. International Academic Journal of Business Management, 2(1), 17–25.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. Harcourt Publishers.

Howard, L. W., & Cordes, C. L. (2010). Flight from unfairness: Effects of perceived injustice on emotional exhaustion and employee withdrawal. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 409–428.

Hystad, S. W., Mearns, K. J., & Eid, J. (2014). Moral disengagement as a mechanism between perceptions of organisational injustice and deviant work behaviours. Safety Science, 68, 138–145.

Jha, J. K., & Varkkey, B. (2018). Are you a cistern or a channel? Exploring factors triggering knowledge-hiding behavior at the workplace: Evidence from the Indian R&D professionals. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(4), 824–849.

Kacmar, K. M., & Carlson, D. S. (1997). Further validation of the Perceptions of Politics Scale (POPS): A multiple sample investigation. Journal of Management, 23(5), 627–658.

Karatepe, O. M. (2013). Perceptions of organizational politics and hotel employee outcomes: The mediating role of work engagement. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(1), 82–104.

Karatepe, O. M., Yorganci, I., & Haktanir, M. (2009). Outcomes of customer verbal aggression among hotel employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 21(6), 713–733.

Kaya, N., Aydin, S., & Ayhan, O. (2016). The effects of organizational politics on perceived organizational justice and intention to leave. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 6(3), 249–258.

Kusluvan, S., Kusluvan, Z., Ilhan, I., & Buyruk, L. (2010). The human dimension: A review of human resources management issues in the tourism and hospitality industry. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(2), 171–214.

Lee, K.-S., Kim, Y.-S., & Shin, H.-C. (2023). Effect of hotel employees’ organizational politics perception on organizational silence, organizational cynicism, and innovation resistance. Sustainability, 15(5), Article 4651.

Miller, B. K., & Nicols, K. M. (2008). Politics and justice: A mediated moderation model. Journal of Managerial Issues, 20(2), 214–237.

Milliken, F. J., & Morrison, E. W. (2003). Shades of silence: Emerging themes and future directions for research on silence in organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1563–1568.

Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. The Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725.

Nadiri, H., & Tanova, C. (2010). An investigation of the role of justice in turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior in hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(1), 33–41.

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2012). Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 216–234.

Niehoff, B. P., & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 527–556.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The assessment of reliability. Psychometric Theory, 3, 248–292.

Oubrich, M., Hakmaoui, A., Benhayoun, L., Söilen, K. S., & Abdulkader, B. (2021). Impacts of leadership style, organizational design and HRM practices on knowledge hiding: The indirect roles of organizational justice and competitive work environment. Journal of Business Research, 137, 488–499.

Peng, H., Bell, C., & Li, Y. (2021). How and when intragroup relationship conflict leads to knowledge hiding: The roles of envy and trait competitiveness. International Journal of Conflict Management, 32(3), 383–406.

Pinder, C. C., & Harlos, K. P. (2001). Employee silence: Quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. In M. Buckley, J. Halbesleben, & A. R. Wheeler (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 331–369). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Poon, J. M. L. (2003). Situational antecedents and outcomes of organizational politics perceptions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(2), 138–155.

Rahim, M. A. (2002). Toward a theory of managing organizational conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, 13(3), 206–235.

Rupp, D. E., & Cropanzano, R. (2002). The mediating effects of social exchange relationships in predicting workplace outcomes from multifoci organizational justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89(1), 925–946.

Shi, X. C., Gordon, S., & Tang, C.-H. H. (2021). Momentary well-being matters: Daily fluctuations in hotel employees’ turnover intention. Tourism Management, 83, Article 104212.

Streicher, B., Jonas, E., Maier, G. W., Frey, D., & Spießberger, A. (2012). Procedural fairness and creativity: Does voice maintain people’s creative vein over time? Creativity Research Journal, 24(4), 358–363.

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 61(1), 37–68.

Taylor, W. A., & Wright, G. H. (2004). Organizational readiness for successful knowledge sharing: Challenges for public sector managers. Information Resources Management Journal, 17(2), 22–37.

Turner, J. H. (2007). Justice and emotions. Social Justice Research, 20(3), 288–311.

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392.

Witt, L. A., Andrews, M. C., & Kacmar, K. M. (2000). The role of participation in decision-making in the organizational politics-job satisfaction relationship. Human Relations, 53(3), 341–358.

Yang, F. (2017). Better understanding the perceptions of organizational politics: Its impact under different types of work unit structure. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(2), 250–262.

Zibenberg, A. (2021). The interaction between personal values and perception of organizational politics in predicting stress levels of staff members in academic institutions. The Journal of Psychology, 155(5), 489–504.

Abubakar, A. M., Behravesh, E., Rezapouraghdam, H., & Yildiz, S. B. (2019). Applying artificial intelligence technique to predict knowledge hiding behavior. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 45–57.

Agag, G., & Eid, R. (2019). Examining the antecedents and consequences of trust in the context of peer-to-peer accommodation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81, 180–192.

Akhbari, M., Tabesh, N., & Ghasemi, V. (2013). Perceived organizational justice, job satisfaction, and OCB: How do they relate to each other? Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 3(7), 512–523.

Alexander, S., & Ruderman, M. (1987). The role of procedural and distributive justice in organizational behavior. Social Justice Research, 1(2), 177–198.

Andrews, M. C., & Kacmar, K. M. (2001). Discriminating among organizational politics, justice, and support. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(4), 347–366.

Aryee, S., Chen, Z. X., & Budhwar, P. S. (2004). Exchange fairness and employee performance: An examination of the relationship between organizational politics and procedural justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 94(1), 1–14.

Bartol, K. M., & Srivastava, A. (2002). Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward systems. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(1), 64–76.

Bies, R. J. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. Research on Negotiation in Organizations, 1(1), 43–55.

Bock, G.-W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y.-G., & Lee, J.-N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87–111.

Bogosian, R., & Stefanchin, J. E. (2018). Employee silence is not always consent. Rutgers Business Review, 3(2), 121–138.

Chen, L., Liu, Y., Hu, S., & Zhang, S. (2022). Perception of organizational politics and innovative behavior in the workplace: The roles of knowledge-sharing hostility and mindfulness. Journal of Business Research, 145, 268–276.

Chiu, C.-M., Hsu, M.-H., & Wang, E. T. G. (2006). Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decision Support Systems, 42(3), 1872–1888.

Collins, C. J., & Smith, K. G. (2006). Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 544–560.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400.

Colquitt, J. A., Greenberg, J., & Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2005). What is organizational justice? A historical overview. In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 3–56). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., & Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(1), 64–88.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Dimitris, B., & Vakola, M. (2007). Organizational silence: A new challenge for human resource management. Athens University of Economics and Business, 6(1), 1–19.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Ghasemi, P., Zomorrodi, A., & Akbari Nasab, J. (2016). Studying the role of organizational justice, commitment and ethical climate in organizational silence. International Academic Journal of Business Management, 2(1), 17–25.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. Harcourt Publishers.

Howard, L. W., & Cordes, C. L. (2010). Flight from unfairness: Effects of perceived injustice on emotional exhaustion and employee withdrawal. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 409–428.

Hystad, S. W., Mearns, K. J., & Eid, J. (2014). Moral disengagement as a mechanism between perceptions of organisational injustice and deviant work behaviours. Safety Science, 68, 138–145.

Jha, J. K., & Varkkey, B. (2018). Are you a cistern or a channel? Exploring factors triggering knowledge-hiding behavior at the workplace: Evidence from the Indian R&D professionals. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(4), 824–849.

Kacmar, K. M., & Carlson, D. S. (1997). Further validation of the Perceptions of Politics Scale (POPS): A multiple sample investigation. Journal of Management, 23(5), 627–658.

Karatepe, O. M. (2013). Perceptions of organizational politics and hotel employee outcomes: The mediating role of work engagement. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(1), 82–104.

Karatepe, O. M., Yorganci, I., & Haktanir, M. (2009). Outcomes of customer verbal aggression among hotel employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 21(6), 713–733.

Kaya, N., Aydin, S., & Ayhan, O. (2016). The effects of organizational politics on perceived organizational justice and intention to leave. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 6(3), 249–258.

Kusluvan, S., Kusluvan, Z., Ilhan, I., & Buyruk, L. (2010). The human dimension: A review of human resources management issues in the tourism and hospitality industry. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(2), 171–214.

Lee, K.-S., Kim, Y.-S., & Shin, H.-C. (2023). Effect of hotel employees’ organizational politics perception on organizational silence, organizational cynicism, and innovation resistance. Sustainability, 15(5), Article 4651.

Miller, B. K., & Nicols, K. M. (2008). Politics and justice: A mediated moderation model. Journal of Managerial Issues, 20(2), 214–237.

Milliken, F. J., & Morrison, E. W. (2003). Shades of silence: Emerging themes and future directions for research on silence in organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1563–1568.

Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. The Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725.

Nadiri, H., & Tanova, C. (2010). An investigation of the role of justice in turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior in hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(1), 33–41.

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2012). Employee voice behavior: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 216–234.

Niehoff, B. P., & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 527–556.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The assessment of reliability. Psychometric Theory, 3, 248–292.

Oubrich, M., Hakmaoui, A., Benhayoun, L., Söilen, K. S., & Abdulkader, B. (2021). Impacts of leadership style, organizational design and HRM practices on knowledge hiding: The indirect roles of organizational justice and competitive work environment. Journal of Business Research, 137, 488–499.

Peng, H., Bell, C., & Li, Y. (2021). How and when intragroup relationship conflict leads to knowledge hiding: The roles of envy and trait competitiveness. International Journal of Conflict Management, 32(3), 383–406.

Pinder, C. C., & Harlos, K. P. (2001). Employee silence: Quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. In M. Buckley, J. Halbesleben, & A. R. Wheeler (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 331–369). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Poon, J. M. L. (2003). Situational antecedents and outcomes of organizational politics perceptions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(2), 138–155.

Rahim, M. A. (2002). Toward a theory of managing organizational conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, 13(3), 206–235.

Rupp, D. E., & Cropanzano, R. (2002). The mediating effects of social exchange relationships in predicting workplace outcomes from multifoci organizational justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89(1), 925–946.

Shi, X. C., Gordon, S., & Tang, C.-H. H. (2021). Momentary well-being matters: Daily fluctuations in hotel employees’ turnover intention. Tourism Management, 83, Article 104212.

Streicher, B., Jonas, E., Maier, G. W., Frey, D., & Spießberger, A. (2012). Procedural fairness and creativity: Does voice maintain people’s creative vein over time? Creativity Research Journal, 24(4), 358–363.

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Employee silence on critical work issues: The cross level effects of procedural justice climate. Personnel Psychology, 61(1), 37–68.

Taylor, W. A., & Wright, G. H. (2004). Organizational readiness for successful knowledge sharing: Challenges for public sector managers. Information Resources Management Journal, 17(2), 22–37.

Turner, J. H. (2007). Justice and emotions. Social Justice Research, 20(3), 288–311.

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392.

Witt, L. A., Andrews, M. C., & Kacmar, K. M. (2000). The role of participation in decision-making in the organizational politics-job satisfaction relationship. Human Relations, 53(3), 341–358.

Yang, F. (2017). Better understanding the perceptions of organizational politics: Its impact under different types of work unit structure. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(2), 250–262.

Zibenberg, A. (2021). The interaction between personal values and perception of organizational politics in predicting stress levels of staff members in academic institutions. The Journal of Psychology, 155(5), 489–504.