Impact of subordinates’ creativity on supervisor undermining: A social dominance perspective

Main Article Content

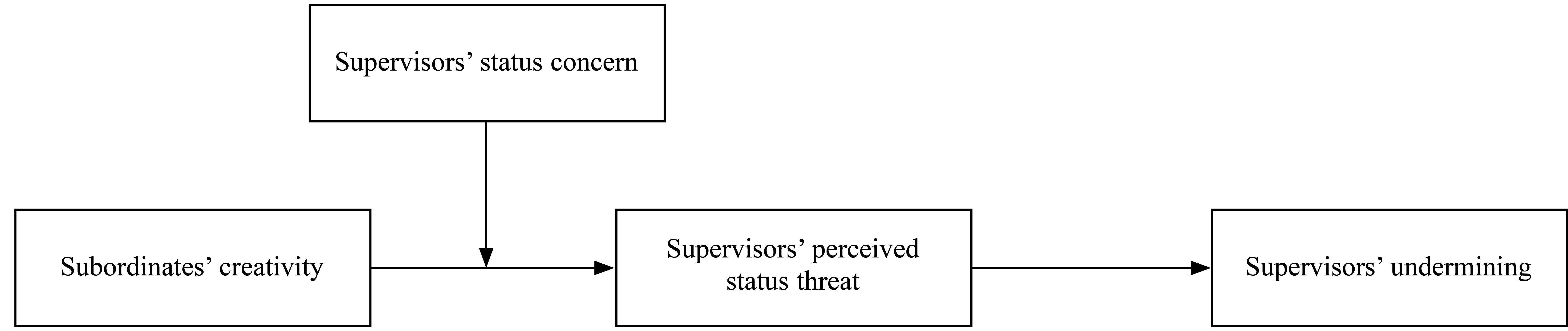

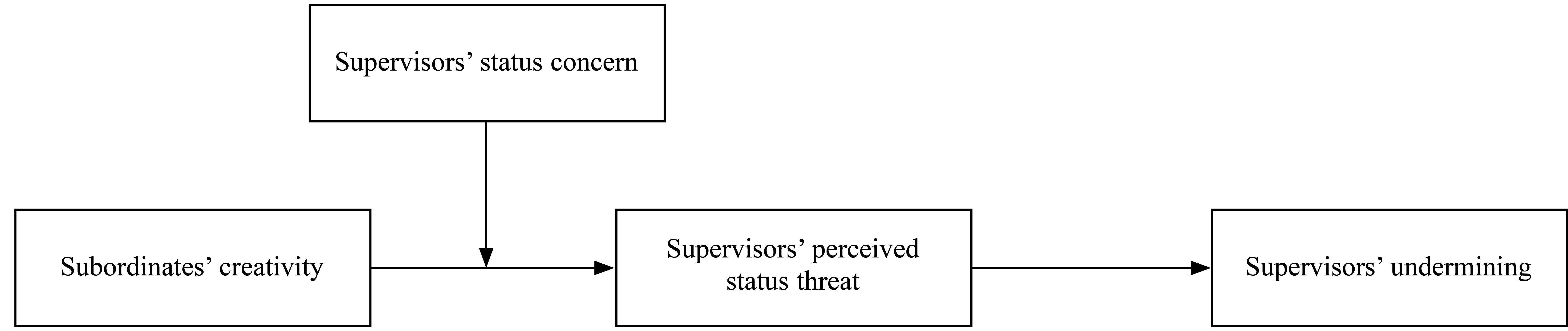

We used the theory of social dominance to explore the mediating influence and boundary conditions according to which subordinates’ creativity affects supervisor undermining. Through a two-stage survey of 223 employees and their paired supervisors, we verified the mediating effect of supervisors’ perceived status threat on the relationship between subordinates’ creativity and supervisor undermining. Supervisors’ status concern moderated the relationship between subordinates’ creativity and supervisors’ perceived status threat. Specifically, the positive relationship between subordinates’ creativity and supervisors’ perceived status threat was stronger when the level of supervisors’ status concern was high. We aimed to deepen understanding of the factors that influence supervisor undermining. Additionally, we introduced perceived status threat as a mediating variable, which enhances understanding of the mechanism behind the unjust treatment of star employees. This highlights the importance of companies continuing to improve the management and professional skills of their supervisors, and fostering an organizational culture that is equal and free, in order to cultivate and retain highly creative talents.

Nowadays, both the general public and academic researchers are increasingly interested in the frequent occurrence of organizational scandals (Piazza & Jourdan, 2018). These scandals shed light on the dark side of leadership behavior and its effect on both organizations and employees (Wu et al., 2018). This trend can be observed in various fields, from news reporting to academic research. Supervisor undermining refers to the hostile behavior of a supervisor in the workplace that prevents subordinates from establishing and maintaining positive interpersonal relationships, achieving work success and good reputation, and achieving work goals. It is specifically manifested in behaviors such as belittling subordinates or their ideas, withholding important or necessary information, talking about subordinates behind their backs, and spreading rumors (Duffy et al., 2002). Existing research shows that subordinates who have been undermined by supervisors have characteristics such as low job satisfaction, high turnover intention, high perceived pressure, and high counterproductive work behavior (Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2013). Owing to the negative impact of this behavior on victims and organizations, researchers have examined the formation mechanism of supervisor undermining to better understand how to reduce its occurrence (Greenbaum et al., 2012).

Existing studies have mainly focused on the impact of supervisors’ personal characteristics on their personal undermining behavior from the perspectives of moral disengagement and a bottom-line mentality (Duffy et al., 2012; Greenbaum et al., 2012), while ignoring whether subordinates’ personal characteristics and behavior lead to the undermining behavior. Supervisor undermining is essentially a negative binary interaction between supervisors and subordinates. Subordinates have many potential opportunities to cause supervisor undermining reactions. For example, supervisors usually suppress subordinates who are deviant and disobedient, and show unfair treatment to subordinates with low performance (Tepper et al., 2011). Previous research has found high-performing subordinates are also vulnerable to abusive management by their supervisors (Khan et al., 2018). Will highly creative employees, as potential star employees, have the same experience? According to social dominance theory (Khan et al., 2018), when high-status individuals realize that the activities, values, and behaviors of low-status individuals may affect the status boundary between them, they will perceive a threat to their existing status (Thomsen et al., 2008). At the same time, to maintain and consolidate the existing status boundary and reduce the inner sense of threat, high-status individuals tend to behave aggressively toward low-status individuals who threaten their status (Davis & Stephan, 2011). In the workplace, if a supervisor thinks that highly creative subordinates have better resources, interpersonal relationships, promotion opportunities, and salary increases, this can create an unclear understanding of the status boundary with their subordinates. To strengthen the existing hierarchy, supervisors may deliberately belittle subordinates’ creative ideas or withhold important information from them. Thus, from the perspective of social dominance, the sense of status threat perceived by supervisors may be an important process mechanism for highly creative subordinates to induce supervisors to implement undermining behavior.

However, not all supervisors have the same level of status threat in the face of highly creative subordinates, which may be related to their personal characteristics. According to social dominance theory, an individual’s perceived status threat is mainly related to their relative position in the community (Ridgeway & Walker, 1995). If individuals pay too much attention to their status, they will be particularly sensitive to information that will affect their status in the surrounding environment (Dovidio et al., 1998). From this perspective, supervisors’ status concern may moderate the relationship between subordinates’ creativity and supervisors’ perceived status threat, which constitutes the boundary condition of the above relationship. To sum up, in this study we integrated and proposed a moderated mediation model to systematically analyze the psychological mechanism and boundary conditions of subordinates’ creativity affecting supervisor undermining behavior, to further understand the formation process of supervisor undermining behavior and to provide guidance for organizations to reduce such behavior.

Subordinate Creativity and Supervisors’ Perceived Status Threat

Supervisors’ Perceived Status Threat and Supervisors’ Undermining

Mediating Role of Supervisors’ Perceived Status Threat

Moderating Role of Supervisors’ Status Concern

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework

Method

Participants and Procedure

We gained ethical approval for this study from our institution and participants gave informed consent before we issued questionnaires. Our research data came from staff in multiple stores of a chain enterprise in Jiangsu Province, China. We adopted the diachronic method, divided into two stages. Via electronic questionnaires we measured demographic variables and four main variables: subordinate creativity, perceived status threat, status concern, and supervisor undermining. In the first stage, subordinate creativity and status concern were collected and questionnaires were completed online by supervisors. After an interval of 1 month, in the second stage, the questionnaire for perceived status threat was completed by supervisors and the questionnaire for supervisors’ undermining was completed separately by the subordinates online.

In advance, the human resources management department of the company coordinated the pairing of store supervisors and their subordinates. Before distributing the questionnaires, the pairing list was entered into the system to generate unique questionnaire links for each supervisor and subordinate. At Time 1 the questionnaire was completed by 80 store supervisors, who provided data on the creativity of 260 subordinates. At Time 2, the 260 evaluated store subordinates were given questionnaires, resulting in 223 valid responses and a response rate of 76.56%. In terms of gender, 143 (64.1%) were men and 80 (35.9%) were women. In terms of age (M = 36.5 years, SD = 7.43), 22 (9.9%) respondents were aged 25 years or under, 38 (17.0%) were aged 26–30 years, 33 (14.8%) were aged 31–35 years, 43 (19.3%) were aged 36–40 years, 66 (29.6%) were aged 41–45 years, and 21 (9.4%) were aged over 45 years. As regards education level, 46 (20.6%) had graduated from junior high school, 34 (15.2%) from technical secondary school, 103 (46.2%) from senior high school, 37 (16.6%) from junior college, and three (1.3%) had an undergraduate degree or higher level of education. Finally, in terms of work tenure (M = 1.33, SD = 0.70), 90 (40.4%) had worked at the company for under 1 year, 91 (40.8%) for 1–2 years, and 42 (18.8%) for 2–3 years.

Measures

To ensure the effectiveness of the measurement tools, we selected mature scales published in foreign authoritative journals and followed a strict translation/back-translation method conducted by a doctoral candidate in Business Administration at Nanjing University to ensure the semantic integrity and accuracy of the items. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Creativity

For the measurement of creativity we used the four-item scale compiled by Farmer et al. (2003). A sample item is “This subordinate takes the lead in putting forward new ideas or methods.” Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient was .83 for this study.

Perceived Status Threats

We measured perceived status threat by adopting the three-item scale compiled by Khan et al. (2018). A sample item is “I feel my status will be threatened by the performance of this subordinate.” Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient was .76 for this study.

Status Concern

We measured status concern with the five-item scale revised by Kilduff et al. (2016), which is based on the research of Blader and Chen (2011). A sample item is “I strive to have higher status than this subordinate.” Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient was .83 for this study.

Supervisor Undermining

For the measurement of supervisor undermining we adopted the five-item scale compiled by Vinokur and Van Ryn (1993). A sample item is “When I ask my supervisor about the workflow, they sometimes belittle me.” Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient was .80 for this study.

Control Variables

We controlled for the corresponding demographic variables of subordinates, including gender (1 = male, 2 = female), age, education level (1 = junior high school, 2 = technical secondary school, 3 = senior high school, 4 = junior college, 5 = undergraduate), and working tenure (calculated according to the actual number of years) to exclude the influence of these factors.

Results

Common Method Variance

For the four main variables in this study we performed Harman’s single-factor test before conducting an exploratory factor analysis. The results showed that the first factor without rotation explained 31.28% of the variance, which does not exceed the 40% standard, so common method bias was not a significant concern in this study.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

We also conducted a confirmatory factor analysis of the variables involved in the model. The results showed that the fit indices of the four-factor model (subordinate creativity, perceived status threat, status concern, supervisor undermining), chi square/degrees of freedom = 2.03, root mean square error of approximation = .07, comparative fit index = .92, Tucker–Lewis index = .91, standardized root mean square residual = .06, displayed strong discriminant validity.

Descriptive Statistical Analysis and Correlation Coefficients of Variables

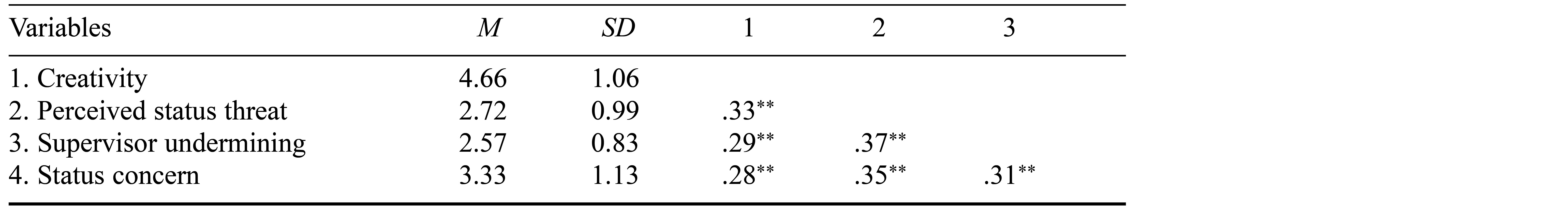

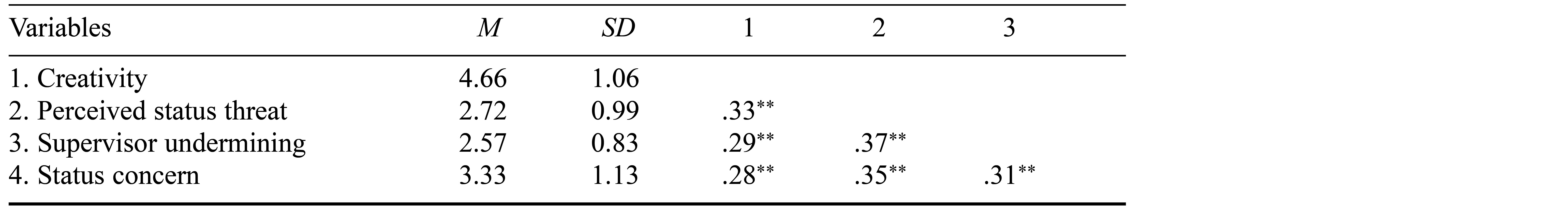

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients among the main variables. These results preliminarily supported Hypotheses 1 and 2.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Study Variables

Note. * p < .05. ** p < .01.

Hypothesis Testing

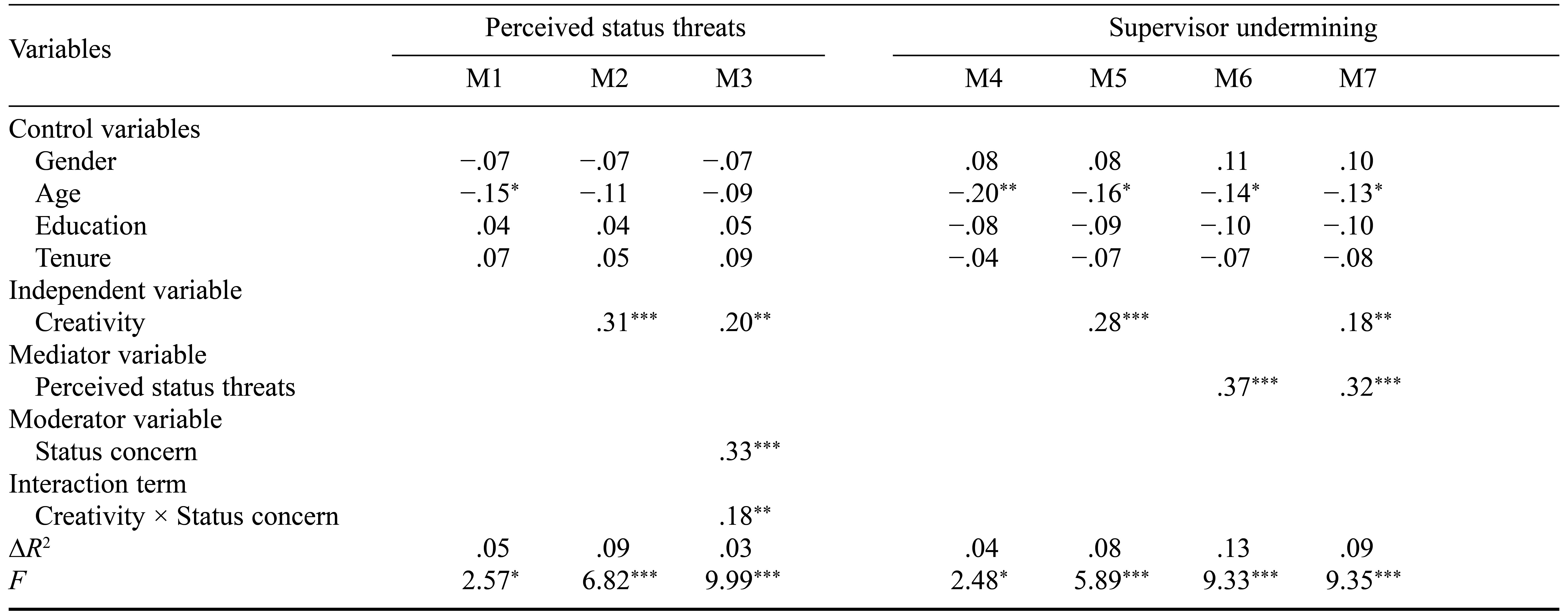

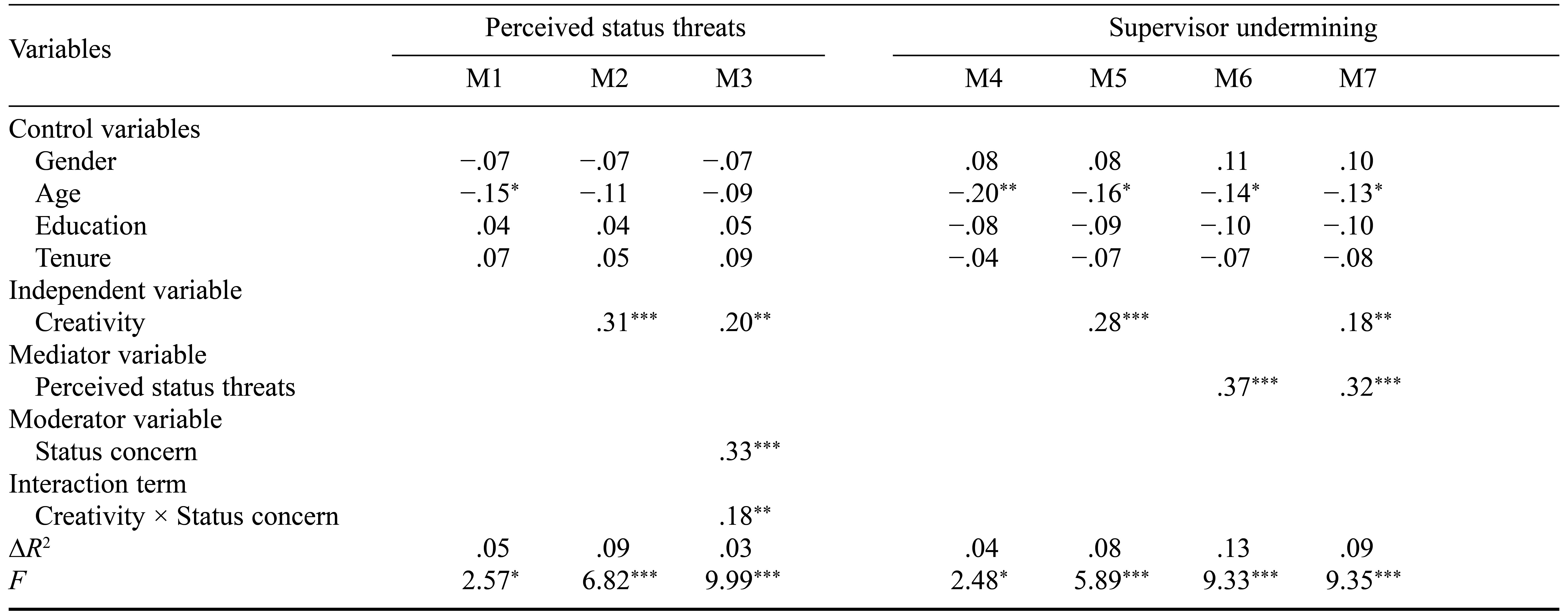

In this study we used hierarchical regression to test the hypotheses. Table 2 shows that the creativity of subordinates had a significant positive impact on the perceived status threat of supervisors, supporting Hypothesis 1. Perceived status threat had a significant positive impact on supervisor undermining, supporting Hypothesis 2. The significant impact of subordinates’ creativity on supervisor undermining decreased with the introduction of the variable of supervisor perceived status threat (from M5 to M7, β decreased from .28 to .18); thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported by the data, that is, the status threat perceived by supervisors played a partial mediating role in the relationship between employee creativity and supervisor undermining.

Table 2. Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis

To further test the mediating effect of position threat perceived by supervisors, we used bootstrapping analysis to repeat sampling 5,000 times via the PROCESS macro. The results showed that perceived status threat mediated the relationship between subordinates’ creativity and supervisor undermining, Boot 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.04, 0.13], which also supported Hypothesis 3.

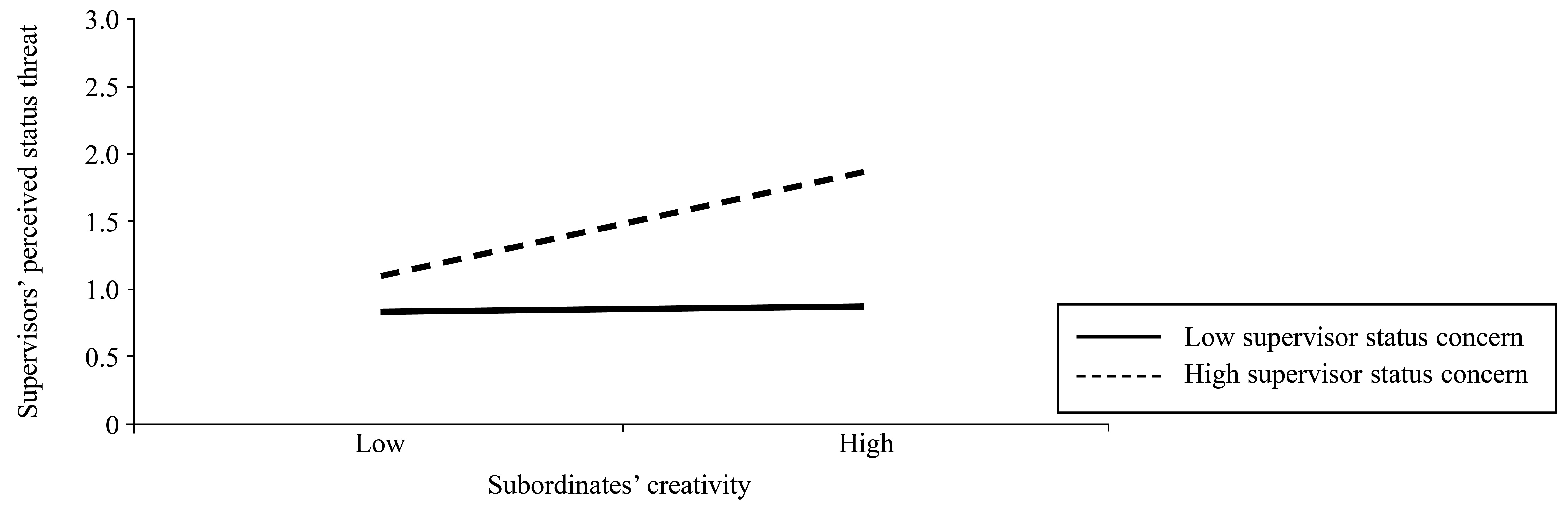

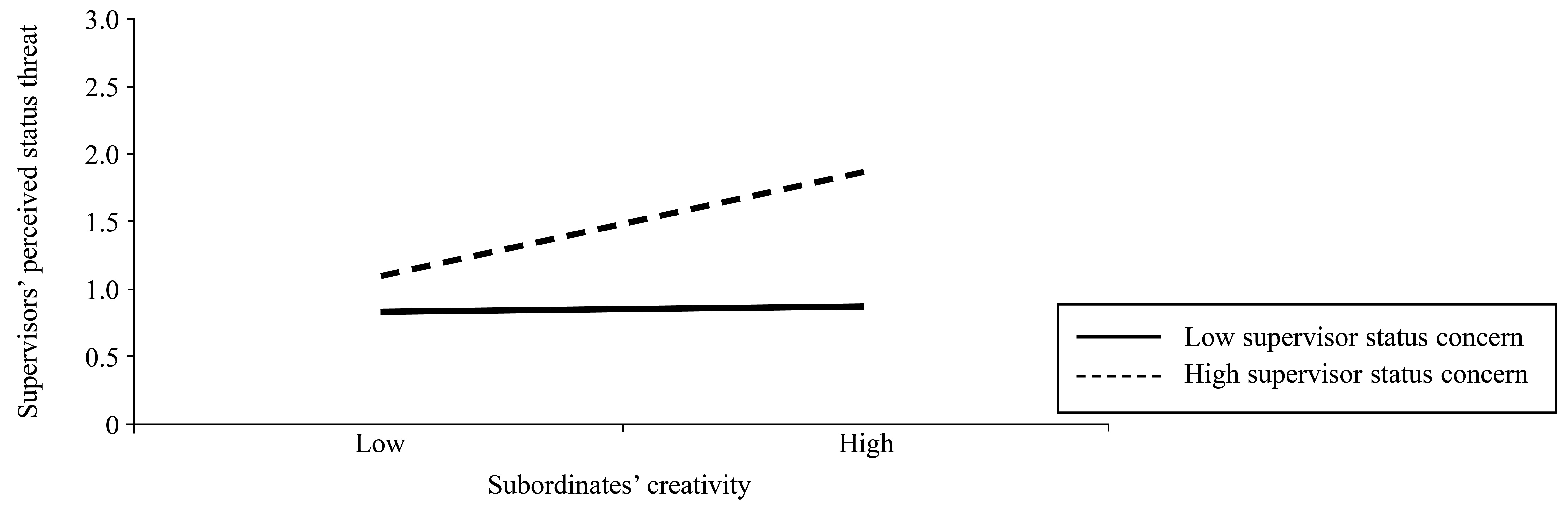

It can be seen from M3 in Table 2 that the regression coefficient of the interaction term between subordinates’ creativity × supervisors’ status concern on supervisors’ perceived status threat was .18 (p < .01), indicating that supervisors’ status concern played a significant positive moderating role in the relationship between subordinates’ creativity and supervisors’ perceived status threat. At the same time, Figure 2 shows there was a positive moderating effect of supervisors’ status concern on the relationship between subordinates’ creativity and the status threat perceived by supervisors. As shown in Figure 2, the higher the supervisors’ status concern, the stronger was the positive effect of subordinates’ creativity on the status threat perceived by the supervisor, and vice versa. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Figure 2. Moderating Role of Supervisors’ Status Concern in the Relationship Between Subordinates’ Creativity and Perceived Status Threat

For further verification of the moderating effect of supervisors’ status concern on the indirect relationship of subordinates’ creativity → perceived status threat → supervisor undermining, we also used bootstrapping via the PROCESS macro. The results show that the indirect effect of subordinates’ creativity → perceived status threat → supervisor undermining was significant under the condition of a high level of supervisors’ status concern, Boot 95% CI [0.03, 0.16]. In contrast, at a low level of supervisor status concern, the indirect effect of subordinates’ creativity → perceived status threat → supervisor undermining was not significant, Boot 95% CI [−0.03, 0.07]. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was verified.

Discussion

In this study we obtained the following main findings: First, subordinates’ creativity has a significant positive impact on supervisors’ perceived status threat and their undermining behavior. Second, supervisors’ status concern positively moderates the influence of subordinates’ creativity on supervisors’ perceived status threat, and also moderates the indirect effect of subordinates’ creativity on supervisors’ undermining behavior through the supervisor’s perceived status threat.

Theoretical Contribution

First, this research expands understanding of the antecedents of supervisor undermining behavior. Previous studies have mostly explored how the individual characteristics of supervisors promote supervisor undermining behavior, and have ignored the impact of subordinate characteristics and behaviors on supervisor undermining (Duffy et al., 2012). In view of this, beginning with the characteristics of subordinates, we introduced the variable of subordinates’ creativity, which enriches research on the antecedent variables of supervisor undermining behavior. Our research conclusion is also an effective response to the call of scholars to pay attention to the influencing factors of supervisor undermining behavior (Duffy et al., 2012; Greenbaum et al., 2012) to effectively avoid or reduce the occurrence of such behavior.

Second, the introduction of social dominance theory further enriches empirical research using this theory. According to the framework of social dominance theory, sense of status threat plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between subordinates’ creativity and supervisor undermining behavior. We consider the research conclusions of this paper to be a powerful supplement to previous research on how subordinate characteristics trigger supervisor undermining behavior, expanding understanding of the mediating mechanism of the relationship between the two, and providing empirical support for the theory of social dominance.

Last, we found that supervisors’ status concern has an impact on the sense of status threat caused by subordinates’ creativity, and on the indirect relationship between subordinates’ creativity and supervisor undermining behavior through status threat. From the perspective of supervisors’ personal characteristics, this emphasizes the important role of supervisors’ personal attitude and behavior in the process of supervisor undermining, and expands the boundary conditions of the formation process of supervisor undermining.

Practical Implications

This research found that highly creative subordinates are more likely to be undermined by supervisors. Enterprises can take measures to avoid such events. First, highly creative subordinates should pay attention to timely communication with supervisors, express their ideas in a flexible way (Greenbaum et al., 2012), and strive to obtain the support of supervisors for their own opinions and ideas, so as to realize the transformation from creativity to innovation performance. Second, enterprises should pay attention to improving supervisors’ management ability and professional skills, so that they have the confidence to accept the doubts and challenges of their subordinates, and have the ability to work with their subordinates to make suggestions for the development of the organization (Greenbaum et al., 2012). Third, in creating an equal and free organizational culture and establishing a reward and promotion system (Khan et al., 2018), the enterprise should support and encourage employees to give full play to their creativity and subjective initiative.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study also has some limitations. First, the data were collected with a questionnaire survey. Follow-up research could use more objective data, such as the number of creative ideas put forward by employees in the enterprise, or could use the situational experiment method to improve the persuasiveness of the research conclusions. Second, we used the theoretical framework of social dominance to explore the impact of subordinates’ creativity on supervisor undermining behavior. The research conclusions supported the hypotheses put forward in this paper. However, whether there are other mechanisms between them, such as the power dependence state from the supervisor (Wee et al., 2017), is worthy of attention in follow-up research. Third, this study examined only the moderating effect of supervisors’ attention to status on the relationships between subordinates’ creativity, the perceived status threat of the supervisor, and the supervisor’s undermining behavior. In the future, other possible factors can be further explored, such as the power distance orientation between supervisor and subordinate, the supervisor’s social dominance tendency (Hu & Liu, 2017), their effects on supervisors’ perception of subordinates’ attitude and behavior, and the effect of undermining behavior.

References

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Study Variables

Note. * p < .05. ** p < .01.

Table 2. Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Figure 2. Moderating Role of Supervisors’ Status Concern in the Relationship Between Subordinates’ Creativity and Perceived Status Threat

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72202109, 72272078, 71832007) and the National Social Science Foundation of China (20AGL020).

Zhihong Chen, Institute for International Students, Nanjing University, No. 18 Jinyin Road, Gulou District, Nanjing, Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected]