Family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability: A multiple mediation model

Main Article Content

Previous research on family triangulation has mainly focused on nuclear family triangulation. In this study we explored the effects of family-of-origin triangulation on marital stability in China, and the mediating roles of parenting sense of competence and coparenting. Participants were 1,144 Chinese parents aged 24 to 48 years, who completed surveys on family-of-origin triangulation, parenting sense of competence, coparenting, and marital stability. The results show that family-of-origin triangulation was negatively associated with marital stability. This relationship was mediated by coparenting, but the mediating effect of parenting sense of competence was nonsignificant. In addition, parenting sense of competence and coparenting sequentially mediated the relationship between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability. Our findings highlight the risk of harm to marital stability from family-of-origin triangulation.

Triangulation, an important research topic in marriage and family studies, has been confirmed by many researchers to have an important influence on the marriage relationship (Pedro et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017). Triangulation occurs when anxiety between two people increases, and a third person becomes involved in the tension, creating a triangle. This involvement of a third person decreases anxiety in the twosome by spreading it through three relationships (Hu et al., 2015). In this study, the three relationships refer to the family-of-origin triangulation relationship formed by a member of the family of origin (third person) and the couple (twosome). In Chinese society great importance is attached to the vertical parent–child relationship (Wu et al., 2010). As child rearing by grandparents is deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture (Hung et al., 2021), family-of-origin triangulation often occurs in China.

For a nuclear family, namely, a husband and wife and their children, the family-of-origin triangulation often has pernicious effects, for example, causing conflict between the couple (Zhang, 1990) and hindering the establishment of the couple’s personal authority (Hu et al., 2015), thus affecting the quality of their marital relationship (Yuan, 2019). However, although Chinese couples aged 30–45 years need to establish personal authority, as they may still depend on their parents for economic needs or social interaction, they cannot establish personal authority. Therefore, family-of-origin triangulation represents family-of-origin involvement in the couple’s economic needs and social interaction.

Previous researchers have mostly explored the triangulation phenomenon in Western countries, regarding gender differences in the differentiation of family of origin (Lim & Lee, 2020) and the influence of family of origin on new marital relationships (Monk et al., 2021). Few have explored the impact of the family-of-origin triangulation in the Chinese context (Hu et al., 2015; Yuan, 2019). Filial piety is fundamental in Chinese traditional culture, and the traditional vertical parent–child relationship is very important. Therefore, family-of-origin involvement with grandchildren is common. In addition, both parents continue to work in paid employment after childbirth (Chen et al., 2011). As the resulting family-of-origin triangulation has a number of implications for the couple’s marriage, we explored the impact of family-of-origin triangulation on marital stability and its mediating mechanism in Chinese culture.

Family-of-origin triangulation is negatively associated with marital stability, because family-of-origin involvement in the marriage damages the couple’s relationship, leading to family conflict and affecting the couple’s happiness (Yuan, 2019). In addition, family-of-origin triangulation is a destructive factor that damages the boundaries and functioning of the husband–wife subsystem, impeding their social and psychological space, and their mutual emotional support, leading to a decline in marital stability (Yuan, 2019). Previous researchers have also shown that family-of-origin triangulation reduces the quality of the marital relationship (Bowen, 1993; Hu et al., 2015). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Family-of-origin triangulation will be negatively associated with marital stability.

Parenting sense of competence is operationalized as a person’s perceived satisfaction and self-efficacy in the parenting role (Studts et al., 2019). Most previous researchers have explored the factors influencing parenting sense of competence in terms of external environment (stress) and the nuclear family (parent–child communication; Buchanan-Pascall et al., 2021; Jandrić & Kurtović, 2021; Richardson et al., 2020), rather than the family-of-origin role. In China, because of the importance of the vertical parent–child relationship, grandparents participate in the child-rearing of their grandchildren, acting as primary caregivers, and helping parents with child-rearing difficulties. Therefore, parents do not see family-of-origin triangulation as harmful (Chen et al., 2011). Previous studies have shown that this coparenting relationship is significantly positively correlated with parenting sense of competence (Li & Liu, 2019). This is explained by social loafing, namely, when people work with other group members to accomplish a task, less effort is required when they work together (vs. alone), and their activity enthusiasm and efficiency are reduced (Latané, 1981). Thus, when grandparents help parents raise their children, parental responsibility is ignored, and parents’ sense of parenting competence is reduced. Therefore, family-of-origin triangulation may lead to parents’ low sense of competence. Moreover, parenting sense of competence may be a negative predictor of the couple’s marital stability. Previous researchers have found that parenting sense of competence had a significant predictive effect on parenting stress (Jackson & Moreland, 2018; Oltra-Benavent et al., 2020), which is an important determinant of divorce (DeLongis & Zwicker, 2017; Jones et al., 2021). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Parenting sense of competence will play a mediating role in the relationship between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability.

The quality of the coparenting relationship in family functioning is reflected by the degree to which parents are partners or adversaries in child rearing. Parents need to adjust their parenting style in the different stages of their children’s development, including communicating and expressing their feelings about their views of their children’s education, for example. With consistent thoughts and behavior, their parenting will then be coordinated and problems dealt with (Schmidt et al., 2021). However, excessive involvement of grandparents owing to family-of-origin triangulation often prevents couples from communicating and expressing their feelings (Hu et al., 2015). Lack of communication between the couple can lead to lower levels of coparenting.

On the other hand, in China’s transition economy, when family-of-origin triangulation occurs, grandparents’ help with childcare enables parents to continue in paid employment and maintain the family income after childbirth (Chen et al., 2011). This means that parents are less involved in child rearing, resulting in a lower level of coparenting. Thus, the effect of family-of-origin triangulation on couples’ mutual expression of feelings and participation in child-rearing damages their coparenting relationship. A low level of coparenting has a negative effect on the stability of the marital relationship. Coparenting plays a dynamic multiple role in the whole family system and is a positive predictor of marital stability (Morrill et al., 2010). Moreover, early coparenting is associated with later marital stability (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004). Previous researchers have also found that coparenting was significantly positively correlated with marital stability (Camisasca et al., 2019; Liu & Wu, 2018). Therefore, a decrease in coparenting is likely to lead to a decrease in marital stability. Previous researchers have also shown that coparenting relationship quality is associated with marital quality (Merrifield, & Gamble, 2013; Riina & McHale, 2015). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Coparenting will mediate the relationship between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability.

Family-of-origin triangulation affects marital stability through the mediating role of the couple’s parenting sense of competence and coparenting relationship. We suggest that parenting sense of competence has an important influence on coparenting by motivating and shaping behavior (Coleman & Karraker, 1998). When parents with low parenting competence have little influence on their children’s behavior, they may feel both less pleasure from interacting with their children and less warmth toward them (Gondoli & Silverberg, 1997). Therefore, when these parents feel unable to change their children’s behavior, they may avoid the difficult task of disciplining them (de Haan et al., 2009). Gillis and Roskam (2019) have shown that parental competence is also related to partner parenting support, that is, those with low parental competence are likely to avoid parenting tasks, resulting in a lower level of coparenting. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Parenting sense of competence and coparenting will sequentially mediate the link between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 1,144 Chinese parents who had a child in kindergarten or primary school. They comprised 460 fathers (40.2%) and 684 mothers (59.8%), aged between 24 and 48 years (M = 34.75, SD = 4.23).

Procedure

We conducted the research via a questionnaire survey. School administrators and participants gave informed consent before the forms were distributed to 40 schools in Henan Province, China. Participants were informed that the survey was anonymous and that they could withdraw at any time. After completing the survey, they were paid RMB 20 (USD 3.20). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University.

Measures

Family-of-Origin Triangulation

We used the eight-item Nuclear Family Triangulation subscale of the Personal Authority in the Family System Questionnaire (Williamson et al., 1984) to measure family-of-origin triangulation. Participants rate the items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = all the time). We changed the word “children” in the original scale to “parents.” A sample item is “Do you often reveal secrets about your marriage to your parents?” The higher the score on the questionnaire, the higher the degree of family-of-origin triangulation. In this study Cronbach’s alpha was .76.

Parenting Sense of Competence

The 16-item Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (Gibaud-Wallston & Wandersman, 1978) measures attitudes about being a parent and parenting. Participants rate their level of agreement with the statements on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). A sample item is “I was sure that any parenting problem could be solved easily.” In this study Cronbach’s alpha was .78.

Coparenting

The 14-item Parents’ Perception of the Co-Parenting Relationship Scale (Stright & Bales, 2003) was used to measure coparenting. Seven items concern supportive coparenting and seven items concern unsupportive coparenting. Participants rate the items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). A sample item is “In general, I feel that my spouse and I have good cooperation in raising our children.” In this study Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Marital Stability

The five-item short form of the Marital Instability Index (Booth et al., 1983) was used to assess participants’ divorce proneness. Participants rate the items on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). To maintain consistency, we carried out reverse scoring for all items, which means the higher the reversed score, the more stable the marriage. Items are “Have you or your partner suggested a divorce or separation?” “Have you discussed divorce or separation with a close friend?” “Have you thought that your marriage was in trouble?” “Have you consulted a lawyer about the division of assets or child custody in a divorce?” “Have you ever seriously thought about divorce or separation?” In this study Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Data Analysis

We used SPSS 21.0 for descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. We conducted bootstrapping analysis to test the multiple mediation model using the PROCESS macro (Model 6; Hayes, 2013). Age and gender were controlled for.

Results

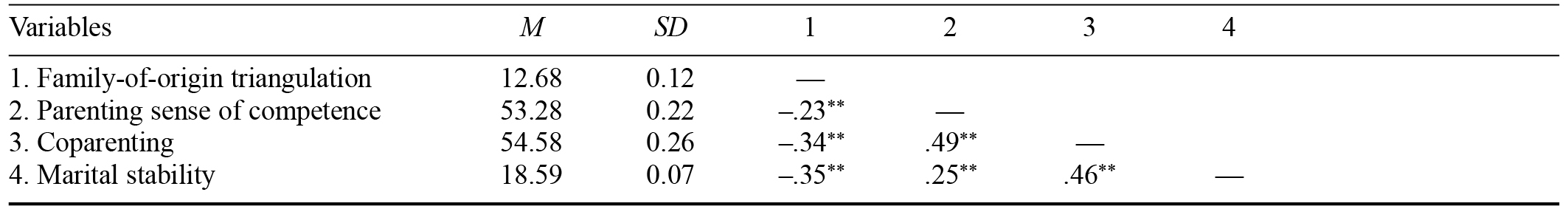

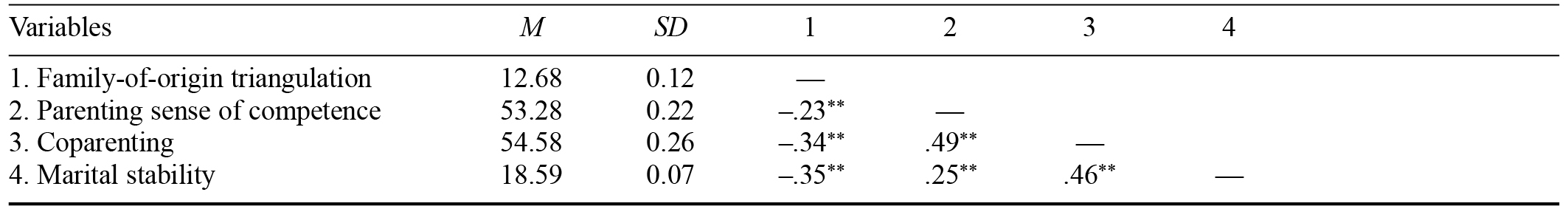

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables are shown in Table 1. Family-of-origin triangulation was negatively associated with parenting sense of competence, coparenting, and marital stability. Parenting sense of competence was positively associated with coparenting and marital stability. Coparenting was positively associated with marital stability. The correlation between the variables was significant, which was consistent with our expectations.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables

Note. N = 905.

* p < .01

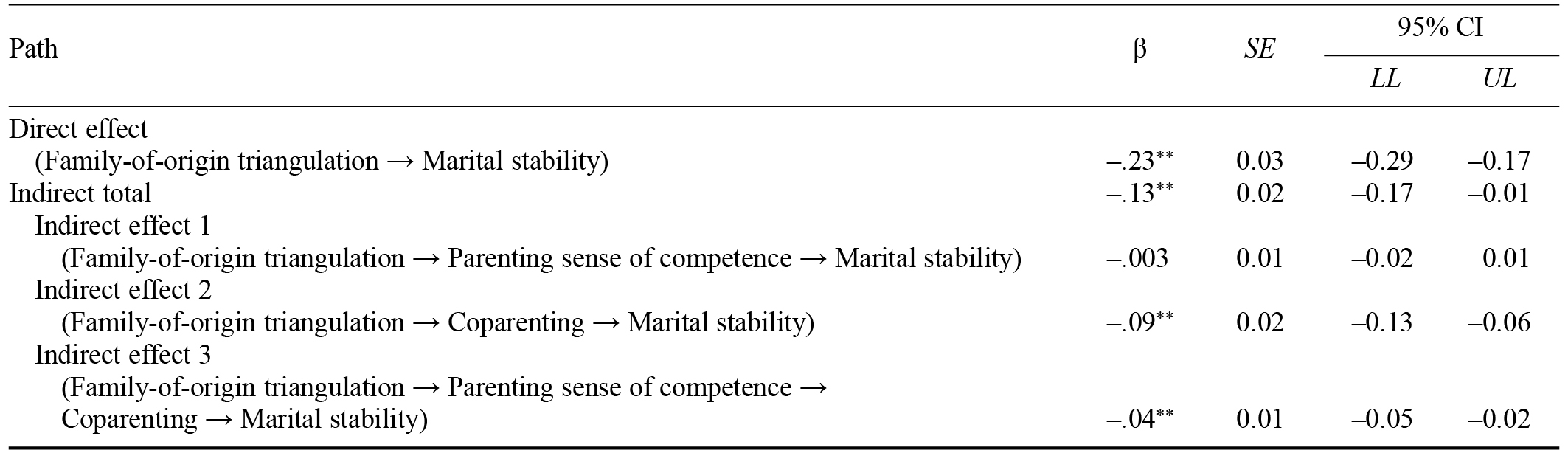

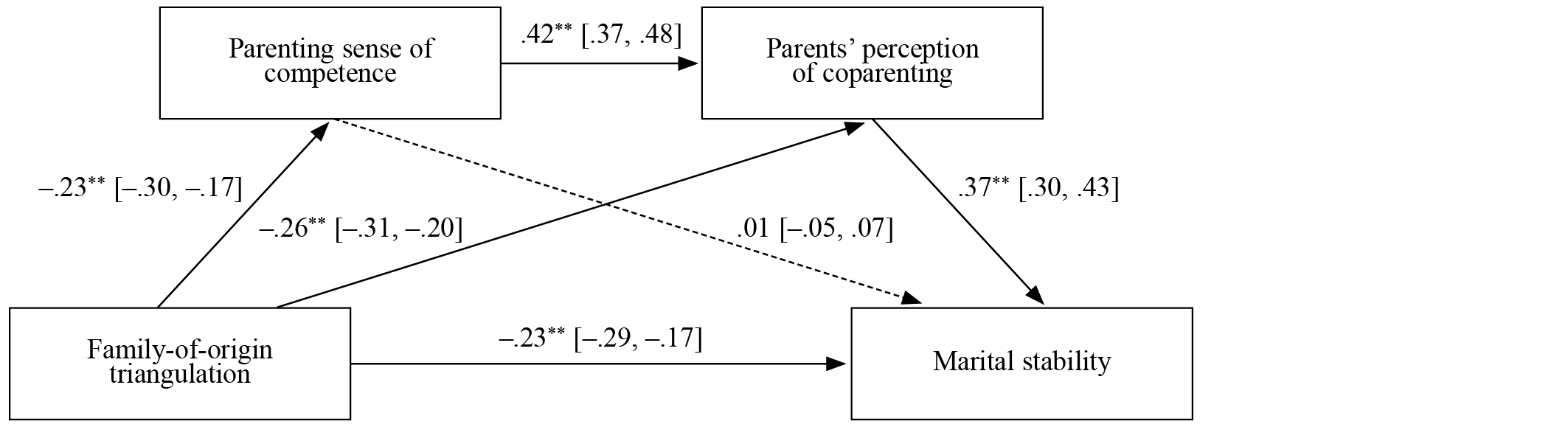

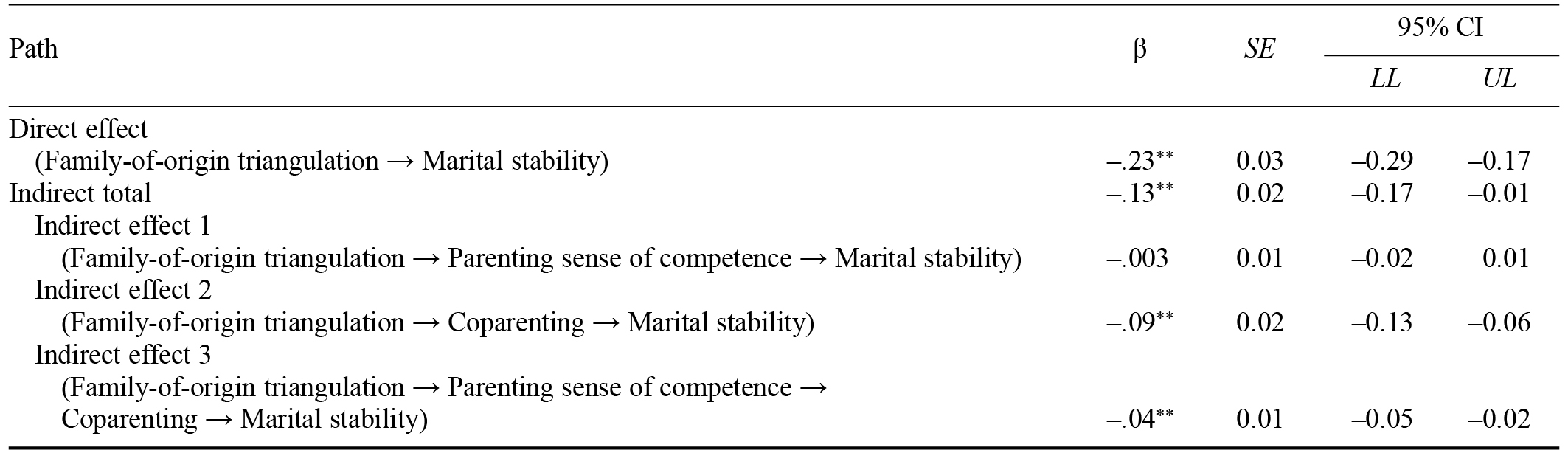

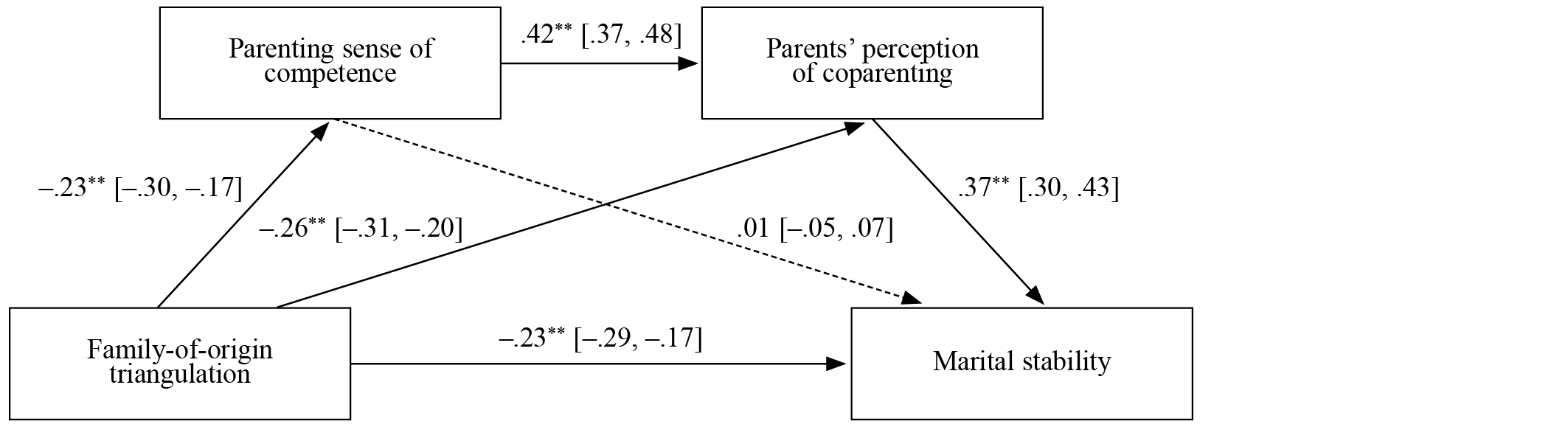

We used the SPSS PROCESS macro (Model 6) to examine the multiple mediating effects of parenting sense of competence and coparenting on the relationship between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability. Bootstrapping analysis was then conducted to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the effects. Results are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2. Test of the Multiple Mediation Model Path

Note. N = 905. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit. Number of bootstrapped resamples = 5,000. Gender and age were controlled for.

** p < .01.

Figure 1. Multiple Mediation Model

Note. ** p < .01.

The results show that after the variables of gender and age had been controlled for, family-of-origin triangulation was significantly negatively associated with marital stability. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Family-of-origin triangulation was negatively associated with marital stability through the mediator of coparenting, and through the multiple mediating effect of parenting sense of competence and coparenting. Therefore Hypotheses 3 and 4 were supported, respectively. However, the mediating effect of parenting sense of competence in the link between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability was nonsignificant. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

The results show that both the path representing family-of-origin triangulation → coparenting → marital stability, and the path representing family-of-origin triangulation → parenting sense of competence → coparenting → marital stability were significant (see Table 2). The path representing family-of-origin triangulation → parenting sense of competence → marital stability was nonsignificant. Thus, parenting sense of competence and coparenting mediated the link between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability, indicating a partial intermediary effect.

Discussion

In this study we have drawn attention to family-of-origin triangulation in China to help couples improve their marital stability. Our results show that family-of-origin triangulation was significantly negatively associated with marital stability, and also negatively associated with marital stability through the mediator of coparenting and the multiple mediating effect of parenting sense of competence and coparenting. However, the parenting sense of competence mediation effect between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability was nonsignificant. Involvement of grandparents from the family of origin in caring for their grandchildren is deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture (Hung et al., 2021). This involvement can reduce the energy parents need to devote to parenting, and as they thus have less responsibility, they have less incentive to be actively involved in child rearing. However, parents’ belief in their ability to accomplish parenting tasks is a key factor in their parenting sense of competence (Salonen et al., 2011). Therefore, family-of-origin triangulation may be negatively associated with parenting sense of competence. All the marital and family functions, comprising values, marriage expectations and obligations, distribution of power and roles between couples, communication, and conflict resolution styles and abilities, have an impact on marital relationships (Olson, 2000). Thus, most factors affecting marital stability focus on the couples’ direct relationship, whereas parenting sense of competence is more closely related to their children. Parenting sense of competence may therefore not have a significant effect on marital stability.

Our results show that coparenting mediated the link between marital stability and family-of-origin triangulation, which was negatively associated with coparenting. This may be because grandparents’ involvement in caring for their grandchildren disrupts the psychologically connected parent–child relationship, contributing to the child’s behavioral problems (Kelley et al., 2011; Smith & Palmieri, 2007). Rodgers-Farmer (1999) found that inconsistencies in the children’s discipline arising from differences between grandparents and parents were significantly associated with parenting stress. This is a challenge for parents and can increase their parental difficulties, causing them to avoid parental tasks and resulting in lower levels of coparenting. Our finding that effective coparenting was significantly positively associated with marital stability confirms previous findings (Camisasca et al., 2019; Liu & Wu, 2018). Marital obligations are very important in marital stability (Olson, 2000). As parenting is a shared obligation, when one spouse fails to fulfill this obligation and the other spouse contributes more to parenting, that spouse is likely to be resentful, leading to conflict and reducing marital stability.

Finally, we found that parenting sense of competence and coparenting sequentially mediated the link between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability. Our finding is consistent with self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1977), in that individuals’ assessment of their abilities directly affected their motivation. Specifically, those with low parenting sense of competence may experience greater stress when performing parental tasks (May et al., 2015). This reduces their motivation and hinders task completion, resulting in less coparenting. Therefore, when family-of-origin triangulation occurs, grandparenting hinders the couple’s original participation in parenting and reduces their parenting sense of competence. They then gradually lose the motivation for parenting, causing one parent to have an unequal share of parenting tasks, undermining coparenting, and leading to lower marital stability.

There are some limitations in this study. First, as the data were self-reported, participants’ responses may have been subjective. Future researchers could incorporate different methods, for example, behavioral observation and an experimental method, to ensure objectivity. Second, all participants were in Henan Province, China, which limits generalizability of the results. Future researchers could expand the geographical scope to compare the variability of participants across regions or countries. Third, we explored only the multiple mediating roles of parenting sense of competence and coparenting. There are many possible mediating variables between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability, for example, marital adjustment and child well-being. Finally, as we used a cross-sectional research design, causality could not be determined. Future researchers could use a longitudinal design to address this.

We have expanded current research by exploring the relationship between family-of-origin triangulation and marital stability in China. Our results illustrate the psychological mechanisms of this relationship and increase recognition of the risk of harm in family-of-origin triangulation.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Booth, A., Johnson, D., & Edwards, J. N. (1983). Measuring marital instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(2), 387–394.

https://doi.org/10.2307/351516

Bowen, M. (1993). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson.

Buchanan-Pascall, S., Melvin, G. A., Gordon, M. S., & Gray, K. M. (2021). Evaluating the effect of parent–child interactive groups in a school-based parent training program: Parenting behavior, parenting stress and sense of competence. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01276-6

Camisasca, E., Miragoli, S., Di Blasio, P., & Feinberg, M. (2019). Co-parenting mediates the influence of marital satisfaction on child adjustment: The conditional indirect effect by parental empathy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(2), 519–530.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1271-5

Chen, F., Liu, G., & Mair, C. A. (2011). Intergenerational ties in context: Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. Social Forces, 90(2), 571–594.

https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sor012

Coleman, P. K., & Karraker, K. H. (1998). Self-efficacy and parenting quality: Findings and future applications. Developmental Review, 18(1), 47–85.

https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1997.0448

de Haan, A. D., Prinzie, P., & Deković, M. (2009). Mothers’ and fathers’ personality and parenting: The mediating role of sense of competence. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1695–1707.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016121

DeLongis, A., & Zwicker, A. (2017). Marital satisfaction and divorce in couples in stepfamilies. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 158–161.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.11.003

Gibaud-Wallston, J., & Wandersman, L. P. (1978). Parenting Sense of Competence Scale. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

https://doi.org/10.1037/t01311-000

Gillis, A., & Roskam, I. (2019). Development and validation of the Partner Parental Support Questionnaire. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 8(3), 152–164.

https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000123

Gondoli, D. M., & Silverberg, S. B. (1997). Maternal emotional distress and diminished responsiveness: The mediating role of parenting efficacy and parental perspective taking. Developmental Psychology, 33(5), 861–868.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.5.861

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hu, W., Sze, Y. T., Chen, H., & Fang, X. (2015). Actor–partner analyses of the relationship between family-of-origin triangulation and marital satisfaction in Chinese couples. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(7), 2135–2146.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0015-4

Hung, S. L., Fung, K. K., & Lau, A. S. M. (2021). Grandparenting in Chinese skipped-generation families: Cultural specificity of meanings and coping. Journal of Family Studies, 27(2), 196–214.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2018.1526703

Jackson, C. B., & Moreland, A. D. (2018). Parental competency as a mediator in the PACE parenting program’s short and long-term effects on parenting stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(1), 211–217.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0859-5

Jandrić, S., & Kurtović, A. (2021). Parenting sense of competence in parents of children with and without intellectual disability. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 17(2), 75–91.

https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.3771

Jones, J. H., Call, T. A., Wolford, S. N., & McWey, L. M. (2021). Parental stress and child outcomes: The mediating role of family conflict. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(3), 746–756.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01904-8

Kelley, S. J., Whitley, D. M., & Campos, P. E. (2011). Behavior problems in children raised by grandmothers: The role of caregiver distress, family resources, and the home environment. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(11), 2138–2145.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.06.021

Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343–356.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.4.343

Li, X., & Liu, Y. (2019). Parent-grandparent coparenting relationship, maternal parenting self-efficacy, and young children’s social competence in Chinese urban families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(4), 1145–1153.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01346-3

Lim, S. A., & Lee, J. (2020). Gender differences in the relationships between parental marital conflict, differentiation from the family of origin, and children’s marital stability. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 48(5), 546–561.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2020.1747370

Liu, C., & Wu, X.-C. (2018). Dyadic effects of marital satisfaction on coparenting in Chinese families: Based on the actor-partner interdependence model. International Journal of Psychology, 53(3), 210–217.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12274

May, C., Fletcher, R., Dempsey, I., & Newman, L. (2015). Modeling relations among coparenting quality, autism-specific parenting self-efficacy, and parenting stress in mothers and fathers of children with ASD. Parenting, 15(2), 119–133.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2015.1020145

McHale, J. P. (1995). Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 985–996.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.31.6.985

Merrifield, K. A., & Gamble, W. C. (2013). Associations among marital qualities, supportive and undermining coparenting, and parenting self-efficacy: Testing spillover and stress-buffering processes. Journal of Family Issues, 34(4), 510–533.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12445561

Monk, J. K., Ogolsky, B. G., Rice, T. M., Dennison, R. P., & Ogan, M. (2021). The role of family-of-origin environment and discrepancy in conflict behavior on newlywed marital quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(1), 124–147.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520958473

Morrill, M. I., Hines, D. A., Mahmood, S., & Córdova, J. V. (2010). Pathways between marriage and parenting for wives and husbands: The role of coparenting. Family Process, 49(1), 59–73.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01308.x

Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 144–167.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00144

Oltra-Benavent, P., Cano-Climent, A., Oliver-Roig, A., Cabrero-García, J., & Richart-Martínez, M. (2020). Spanish version of the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale: Evidence of reliability and validity. Child & Family Social Work, 25(2), 373–383.

https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12693

Pedro, M. F., Ribeiro, T., & Shelton, K. H. (2015). Romantic attachment and family functioning: The mediating role of marital satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(11), 3482–3495.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0150-6

Richardson, A. C., Lo, J., Priddis, L., & O’Sullivan, T. A. (2020). A quasi-experimental study of the respectful approach on early parenting competence and stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(10), 2796–2810.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01762-w

Riina, E. M., & McHale, S. M. (2015). African American couples’ coparenting satisfaction and marital characteristics in the first two decades of marriage. Journal of Family Issues, 36(7), 902–923.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13495855

Rodgers-Farmer, A. Y. (1999). Parenting stress, depression, and parenting in grandmothers raising their grandchildren. Children and Youth Services Review, 21(5), 377–388.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-7409(99)00027-4

Salonen, A., Kaunonen, M., Åstedt-Kurki, P., Järvenpää, A.-L., Isoaho, H., & Tarkka, M.-T. (2011). Effectiveness of an internet-based intervention enhancing Finnish parents’ parenting satisfaction and parenting self-efficacy during the postpartum period. Midwifery, 27(6), 832–841.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.08.010

Schmidt, B., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Frizzo, G. B., & Piccinini, C. A. (2021). Coparenting across the transition to parenthood: Qualitative evidence from South-Brazilian families. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(5), 691–702.

https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000700

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Frosch, C. A., & McHale, J. L. (2004). Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(1), 194–207.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.194

Smith, G. C., & Palmieri, P. A. (2007). Risk of psychological difficulties among children raised by custodial grandparents. Psychiatric Services, 58(10), 1303–1310.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.58.10.1303

Stright, A. D., & Bales, S. S. (2003). Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Family Relations, 52(3), 232–240.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00232.x

Studts, C. R., Pilar, M. R., Jacobs, J. A., & Fitzgerald, B. K. (2019). Fatigue and physical activity: Potential modifiable contributors to parenting sense of competence. Journal of Child and Family Studies 28(10), 2901–2909.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01470-0

Wang, M., Liu, S., & Belsky, J. (2017). Triangulation processes experienced by children in contemporary China. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(6), 688–695.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416662345

Williamson, D. S., Bray, J. H., & Malone, P. E. (1982). Personal authority in the family system questionnaire. Houston Family Institute.

Wu, T.-F., Yeh, K.-H., Cross, S. E., Larson, L. M., Wang, Y.-C., & Tsai, Y.-L. (2010). Conflict with mothers-in-law and Taiwanese women’s marital satisfaction: The moderating role of husband support. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(4), 497–522.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000009353071

Yuan, X. (2019). Family-of-origin triangulation and marital quality of Chinese couples: The mediating role of in-law relationships. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 50(1), 98–112.

https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.042-2017

Zhang, Z. (1990). Development of family systems theory and thinking [In Chinese]. Psychological Exploration, 1, 31–34.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Booth, A., Johnson, D., & Edwards, J. N. (1983). Measuring marital instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(2), 387–394.

https://doi.org/10.2307/351516

Bowen, M. (1993). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson.

Buchanan-Pascall, S., Melvin, G. A., Gordon, M. S., & Gray, K. M. (2021). Evaluating the effect of parent–child interactive groups in a school-based parent training program: Parenting behavior, parenting stress and sense of competence. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01276-6

Camisasca, E., Miragoli, S., Di Blasio, P., & Feinberg, M. (2019). Co-parenting mediates the influence of marital satisfaction on child adjustment: The conditional indirect effect by parental empathy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(2), 519–530.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1271-5

Chen, F., Liu, G., & Mair, C. A. (2011). Intergenerational ties in context: Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. Social Forces, 90(2), 571–594.

https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sor012

Coleman, P. K., & Karraker, K. H. (1998). Self-efficacy and parenting quality: Findings and future applications. Developmental Review, 18(1), 47–85.

https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1997.0448

de Haan, A. D., Prinzie, P., & Deković, M. (2009). Mothers’ and fathers’ personality and parenting: The mediating role of sense of competence. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1695–1707.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016121

DeLongis, A., & Zwicker, A. (2017). Marital satisfaction and divorce in couples in stepfamilies. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 158–161.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.11.003

Gibaud-Wallston, J., & Wandersman, L. P. (1978). Parenting Sense of Competence Scale. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

https://doi.org/10.1037/t01311-000

Gillis, A., & Roskam, I. (2019). Development and validation of the Partner Parental Support Questionnaire. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 8(3), 152–164.

https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000123

Gondoli, D. M., & Silverberg, S. B. (1997). Maternal emotional distress and diminished responsiveness: The mediating role of parenting efficacy and parental perspective taking. Developmental Psychology, 33(5), 861–868.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.5.861

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hu, W., Sze, Y. T., Chen, H., & Fang, X. (2015). Actor–partner analyses of the relationship between family-of-origin triangulation and marital satisfaction in Chinese couples. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(7), 2135–2146.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0015-4

Hung, S. L., Fung, K. K., & Lau, A. S. M. (2021). Grandparenting in Chinese skipped-generation families: Cultural specificity of meanings and coping. Journal of Family Studies, 27(2), 196–214.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2018.1526703

Jackson, C. B., & Moreland, A. D. (2018). Parental competency as a mediator in the PACE parenting program’s short and long-term effects on parenting stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(1), 211–217.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0859-5

Jandrić, S., & Kurtović, A. (2021). Parenting sense of competence in parents of children with and without intellectual disability. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 17(2), 75–91.

https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.3771

Jones, J. H., Call, T. A., Wolford, S. N., & McWey, L. M. (2021). Parental stress and child outcomes: The mediating role of family conflict. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(3), 746–756.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01904-8

Kelley, S. J., Whitley, D. M., & Campos, P. E. (2011). Behavior problems in children raised by grandmothers: The role of caregiver distress, family resources, and the home environment. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(11), 2138–2145.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.06.021

Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343–356.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.4.343

Li, X., & Liu, Y. (2019). Parent-grandparent coparenting relationship, maternal parenting self-efficacy, and young children’s social competence in Chinese urban families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(4), 1145–1153.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01346-3

Lim, S. A., & Lee, J. (2020). Gender differences in the relationships between parental marital conflict, differentiation from the family of origin, and children’s marital stability. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 48(5), 546–561.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2020.1747370

Liu, C., & Wu, X.-C. (2018). Dyadic effects of marital satisfaction on coparenting in Chinese families: Based on the actor-partner interdependence model. International Journal of Psychology, 53(3), 210–217.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12274

May, C., Fletcher, R., Dempsey, I., & Newman, L. (2015). Modeling relations among coparenting quality, autism-specific parenting self-efficacy, and parenting stress in mothers and fathers of children with ASD. Parenting, 15(2), 119–133.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2015.1020145

McHale, J. P. (1995). Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 985–996.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.31.6.985

Merrifield, K. A., & Gamble, W. C. (2013). Associations among marital qualities, supportive and undermining coparenting, and parenting self-efficacy: Testing spillover and stress-buffering processes. Journal of Family Issues, 34(4), 510–533.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12445561

Monk, J. K., Ogolsky, B. G., Rice, T. M., Dennison, R. P., & Ogan, M. (2021). The role of family-of-origin environment and discrepancy in conflict behavior on newlywed marital quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(1), 124–147.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520958473

Morrill, M. I., Hines, D. A., Mahmood, S., & Córdova, J. V. (2010). Pathways between marriage and parenting for wives and husbands: The role of coparenting. Family Process, 49(1), 59–73.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01308.x

Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 144–167.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00144

Oltra-Benavent, P., Cano-Climent, A., Oliver-Roig, A., Cabrero-García, J., & Richart-Martínez, M. (2020). Spanish version of the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale: Evidence of reliability and validity. Child & Family Social Work, 25(2), 373–383.

https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12693

Pedro, M. F., Ribeiro, T., & Shelton, K. H. (2015). Romantic attachment and family functioning: The mediating role of marital satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(11), 3482–3495.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0150-6

Richardson, A. C., Lo, J., Priddis, L., & O’Sullivan, T. A. (2020). A quasi-experimental study of the respectful approach on early parenting competence and stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(10), 2796–2810.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01762-w

Riina, E. M., & McHale, S. M. (2015). African American couples’ coparenting satisfaction and marital characteristics in the first two decades of marriage. Journal of Family Issues, 36(7), 902–923.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13495855

Rodgers-Farmer, A. Y. (1999). Parenting stress, depression, and parenting in grandmothers raising their grandchildren. Children and Youth Services Review, 21(5), 377–388.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-7409(99)00027-4

Salonen, A., Kaunonen, M., Åstedt-Kurki, P., Järvenpää, A.-L., Isoaho, H., & Tarkka, M.-T. (2011). Effectiveness of an internet-based intervention enhancing Finnish parents’ parenting satisfaction and parenting self-efficacy during the postpartum period. Midwifery, 27(6), 832–841.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.08.010

Schmidt, B., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Frizzo, G. B., & Piccinini, C. A. (2021). Coparenting across the transition to parenthood: Qualitative evidence from South-Brazilian families. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(5), 691–702.

https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000700

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Frosch, C. A., & McHale, J. L. (2004). Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(1), 194–207.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.194

Smith, G. C., & Palmieri, P. A. (2007). Risk of psychological difficulties among children raised by custodial grandparents. Psychiatric Services, 58(10), 1303–1310.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.58.10.1303

Stright, A. D., & Bales, S. S. (2003). Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Family Relations, 52(3), 232–240.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00232.x

Studts, C. R., Pilar, M. R., Jacobs, J. A., & Fitzgerald, B. K. (2019). Fatigue and physical activity: Potential modifiable contributors to parenting sense of competence. Journal of Child and Family Studies 28(10), 2901–2909.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01470-0

Wang, M., Liu, S., & Belsky, J. (2017). Triangulation processes experienced by children in contemporary China. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(6), 688–695.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416662345

Williamson, D. S., Bray, J. H., & Malone, P. E. (1982). Personal authority in the family system questionnaire. Houston Family Institute.

Wu, T.-F., Yeh, K.-H., Cross, S. E., Larson, L. M., Wang, Y.-C., & Tsai, Y.-L. (2010). Conflict with mothers-in-law and Taiwanese women’s marital satisfaction: The moderating role of husband support. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(4), 497–522.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000009353071

Yuan, X. (2019). Family-of-origin triangulation and marital quality of Chinese couples: The mediating role of in-law relationships. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 50(1), 98–112.

https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.042-2017

Zhang, Z. (1990). Development of family systems theory and thinking [In Chinese]. Psychological Exploration, 1, 31–34.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables

Note. N = 905.

* p < .01

Table 2. Test of the Multiple Mediation Model Path

Note. N = 905. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit. Number of bootstrapped resamples = 5,000. Gender and age were controlled for.

** p < .01.

Figure 1. Multiple Mediation Model

Note. ** p < .01.

Yongfang Liu, School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University, 3663 North Zhongshan Road, Shanghai 200062, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected]