South Korean college freshmen students’ perceptions of happiness during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020

Main Article Content

Happiness is an important factor influencing academic performance, and many college freshmen have experienced adjustment difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic. We applied Q methodology to explore South Korean freshmen students’ perceptions of happiness in 2020. Participants were divided into three groups according to perceptions of happiness: (a) those who considered relationships as vital for happiness, (b) those who considered freedom to have new experiences as vital for happiness, and (c) those who considered setting and achieving goals as vital for happiness. These findings can serve as basic data for the development of curricula and programs to help college freshmen adapt to college life.

Freshmen students’ adjustment to college life is pivotal because it is a transition to adulthood in which they assume independence and responsibility for their behavior (K. H. Kim & Kang, 2016). Young people face great stress in adapting to the complex social environment at college (Jeong, 2018). In particular, students who entered college in 2020 faced an unexpected situation with the COVID-19 pandemic, experiencing additional stress and adjustment difficulties (Bono et al., 2020; Rager, 2020). College students have encountered severe difficulties in their academic endeavors, in daily life, and with mental health issues, experiencing depression, anxiety, mood fluctuations, and even suicidal thoughts during the pandemic (Gupta et al., 2021; Kecojevic et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Previous studies have indicated that happiness fortifies college freshmen against stress and improves their adaptation to college life (Xu et al., 2019). Happiness is defined as a person having a positive attitude toward life, and a positive disposition to experience satisfaction and joy in important areas of life, such as work, love, play, and child-rearing (Joodat & Zarbakhsh, 2015; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). Seligman et al. (2005) found that happiness is a life habit and skill that anyone can cultivate through discovery and practice.

College students’ happiness has been studied in multiple countries. Peltzer and Pengpid (2013) found in their study conducted with Indian college students that daily routines, such as having normal sleeping hours (i.e., 7–8 hours) and eating breakfast regularly, contributed to happiness. According to Tarrahi and Nasirian’s (2017) study conducted at Iran’s Khorramabad University, happiness was positively related to physical activity and negatively related to smoking cigarettes. Karaşar and Baytemir (2018) found in their study conducted with Turkish college students that a greater desire for social approval was associated with greater social anxiety and less happiness. According to Abdel-Khalek and Lester’s (2017) study conducted with Arab college students, individuals who considered themselves as more (vs. less) religious were happier.

In addition, studies on college students’ happiness have varied in their content with respect to factors influencing happiness, scale development, and the testing of programs for improving happiness. Studies on the factors affecting happiness have shown that social support, cooperative learning, cognitive flexibility, academic success, financial stability, family support, peer support, life satisfaction, religious maturity, and living environment contribute to college students’ happiness (Bum & Jeon, 2016; Demirtaş, 2020; Flynn & MacLeod, 2015; Jang, 2020; Koçak, 2008). Further, Jo and Park (2019) showed that happiness can improve college students’ gratitude, self-esteem, and flow.

Nevertheless, happiness differs according to individual characteristics, and current research on subjective perceptions of happiness is insufficient (Choi & Cho, 2016; Cloninger & Zohar, 2011). An examination of factors affecting college freshmen’s happiness may help to find ways to foster happiness tailored to each individual. As predetermined variables have previously been measured quantitatively, these results may be limited regarding participants’ true thoughts about happiness (Economos et al., 2008; K. Kim & Lim, 2012; H. Zhang & Dai, 2018; R. P. Zhang, 2016).

Therefore, to examine the subjective elements of happiness as perceived by college freshmen, with the aim of improving their happiness and facilitating their adjustment to college life, we posed two research questions:

Research Question 1: How can college freshmen students’ subjective perceptions of happiness be grouped?

Research Question 2: What are the characteristics of the resulting grouped perceptions found with the use of Q methodology?

Method

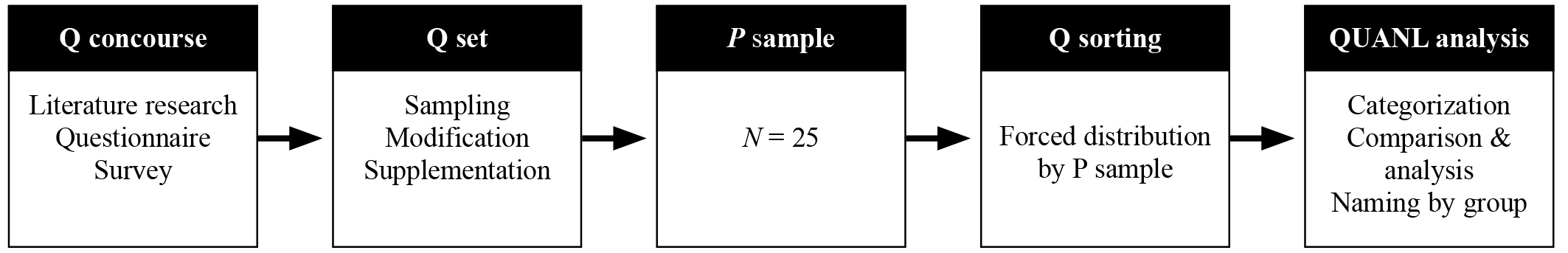

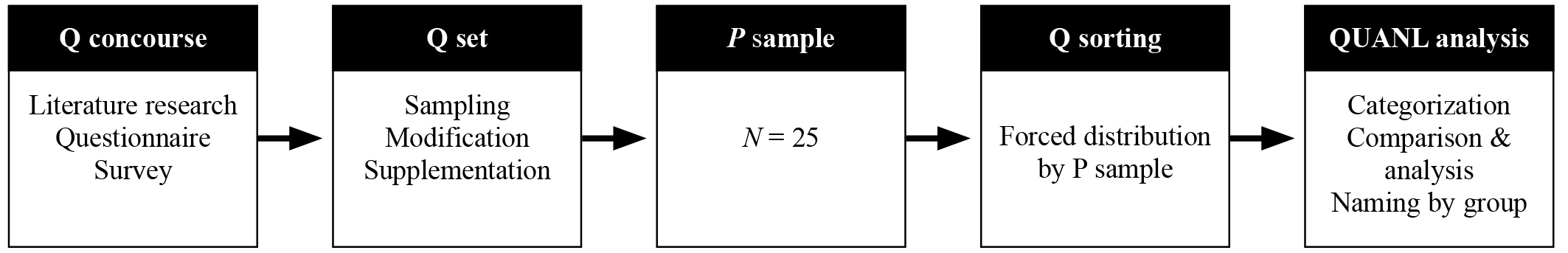

Q methodology combines qualitative and quantitative methods to better understand individuals’ subjective perceptions of a specific phenomenon (Herrington & Coogan, 2011). This methodology is useful for addressing the limitations of a quantitative approach, because it involves the systematic compiling and objective analysis of the cultures, perceptions, cognitions, and attitudes of groups in a given environment. It is also suitable for analyzing the internal structure of individual perceptions of what constitutes happiness (H. K. Kim, 2008). Thus, Q methodology is appropriate for examining college students’ subjective perceptions of happiness because the statements are presented from the participants’ (vs. the researcher’s) perspective. In the research process, researchers create a Q concourse, select a Q set and P sample, collect data using Q sorting, and analyze the data and interpret the results via QUANL analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Research Process

Q Concourse

A Q concourse consists of the collection of ideas, values, and attitudes about a specific topic. To create the Q concourse, we compiled survey items regarding happiness through a literature review. We also conducted a semistructured survey with 120 freshman college students at Dongguk University, in which we asked them to write about their ideas of happiness. The resulting concourse comprised a diverse range of content regarding happiness, such as relationships, desires, and self-development.

Q Set

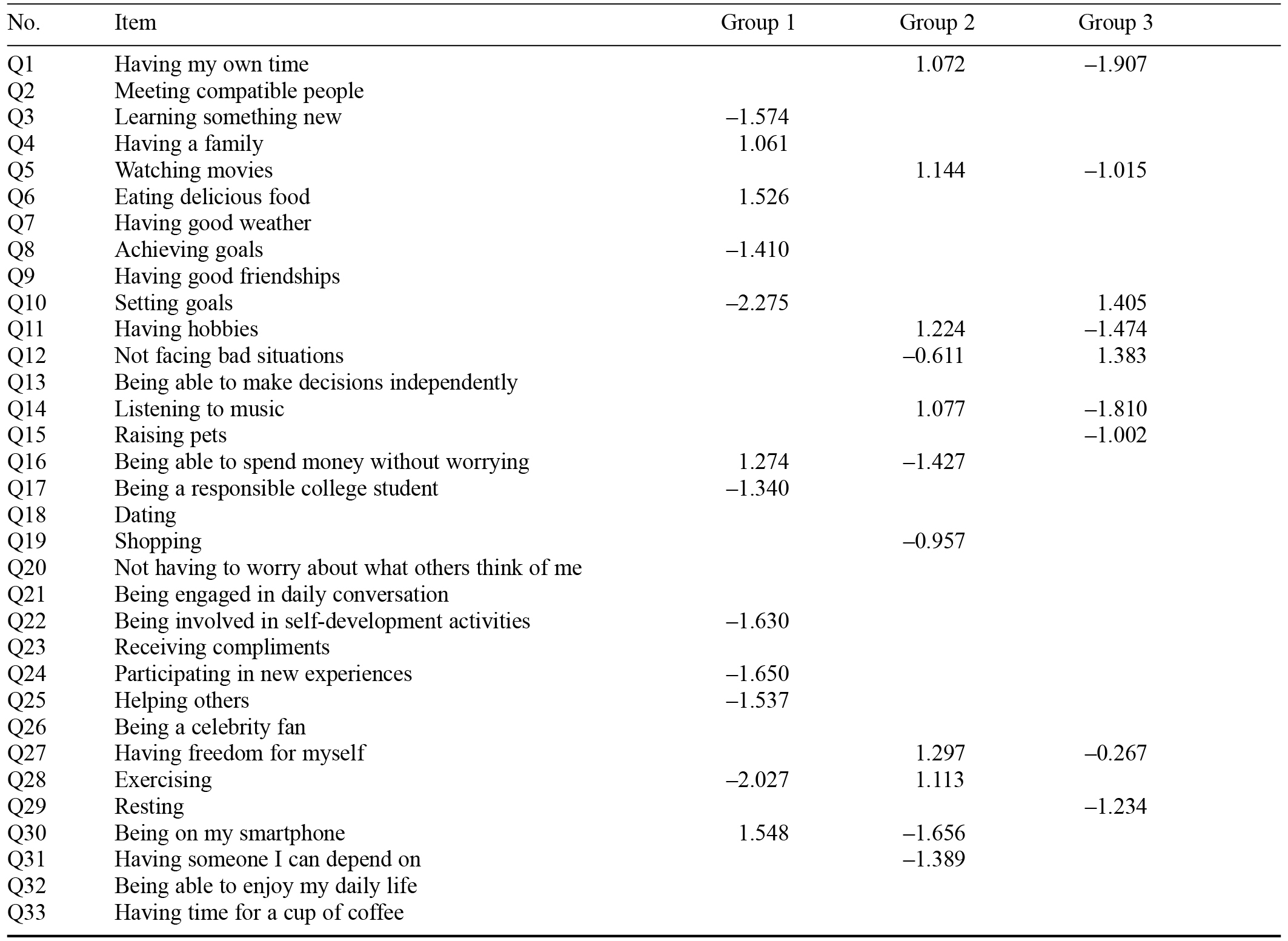

A Q set is a broad representative sample composed of items selected from the Q concourse through the repeated review and exclusion of overlapping material. We selected the most diverse ideas about happiness to create the 33 items for the Q set (see Table 3).

P Sample

A P sample is a small group of participants who are theoretically relevant to the specific topic (Brown, 1980). Hylton et al. (2018) claimed that demographic representativeness is not necessary for a P sample because the primary goal is not to make demographic generalizations. We used purposive sampling to select 25 freshmen students from Dongguk University in Seoul as participants, and conducted the survey during the last week of the first semester of 2020. We thoroughly explained the study’s aims and procedure to the participants before they read and signed the informed consent form.

Q Sorting and Data Analysis

According to Brown (1980), Q sorting is a rank-ordering procedure in which the items are arranged in a way that is significant from the participants’ standpoint. In this study, participants ranked the 33 Q-item cards by dividing them into three piles on a Q-sort table, according to their degree of agreement on a 9-point rating scale ranging from +4 = most agreeable to –4 = most disagreeable. They recorded their reasoning for their two most agreeable and two most disagreeable Q-items. We then analyzed and interpreted the Q-sorts using principal component analysis in the QUANL program. Of the resulting z scores for each perception group, we selected items with eigenvalues exceeding 1.0 only as being significant for interpretation. We analyzed participants’ detailed written descriptions of their selected items, which we deemed significant for a more robust interpretation of the responses.

Results

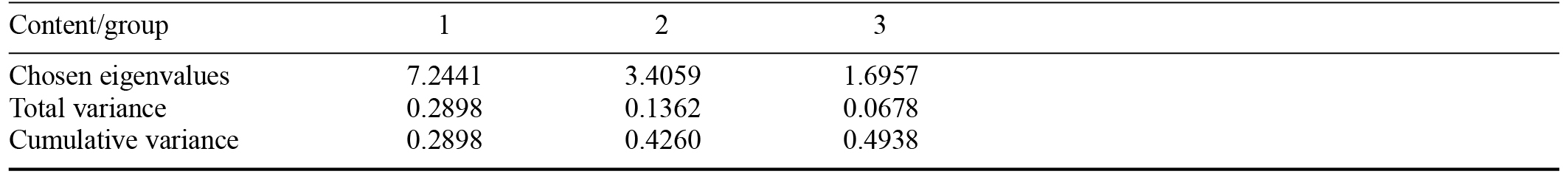

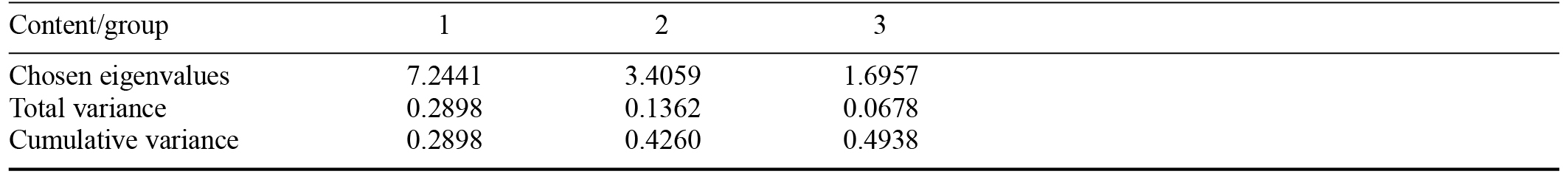

Three groups, each with different perceptions of what made them happy, emerged from the totals (see Table 2). The eigenvalues for each group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Eigenvalues and Explanatory Variance of Perceptions According to Group

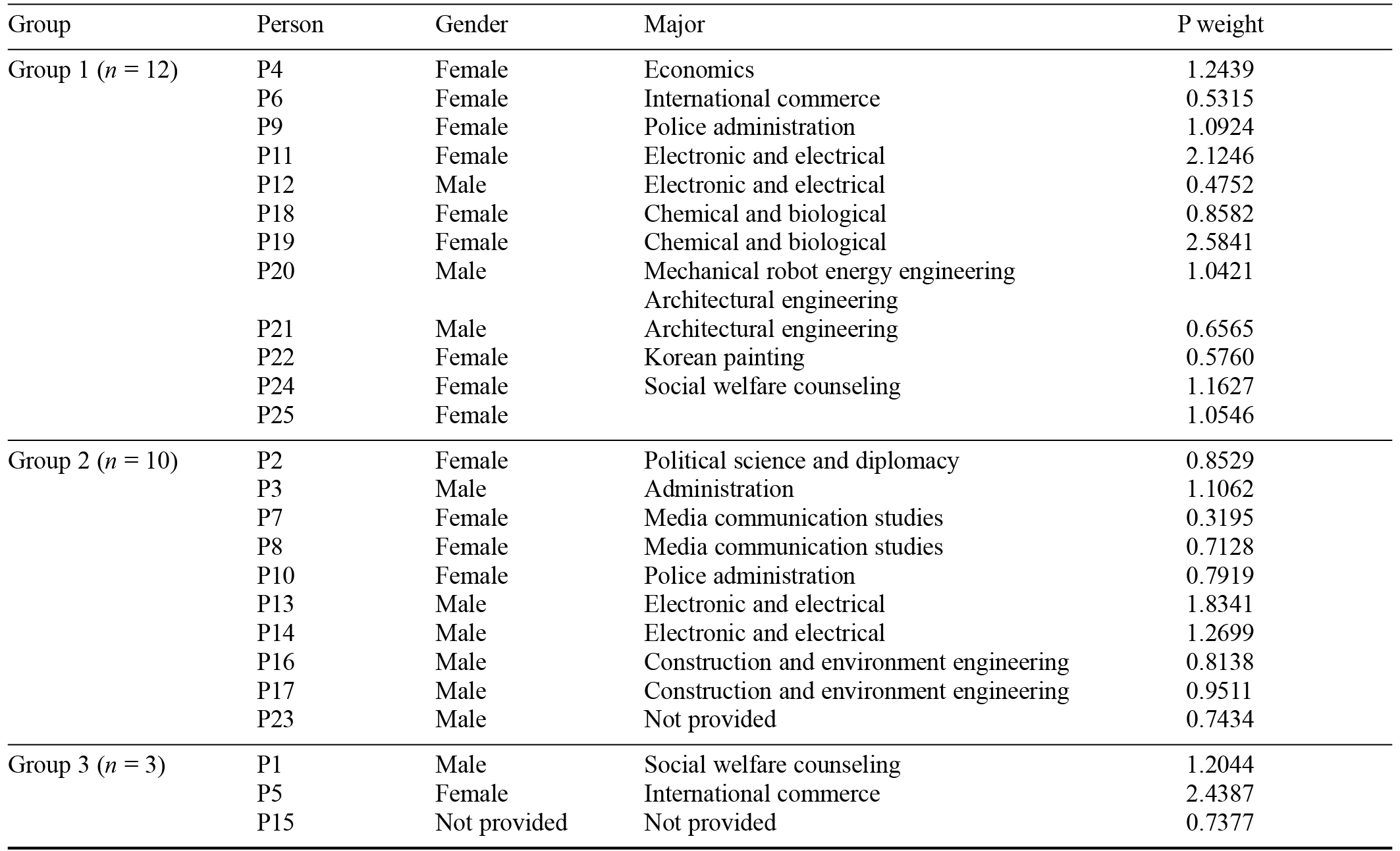

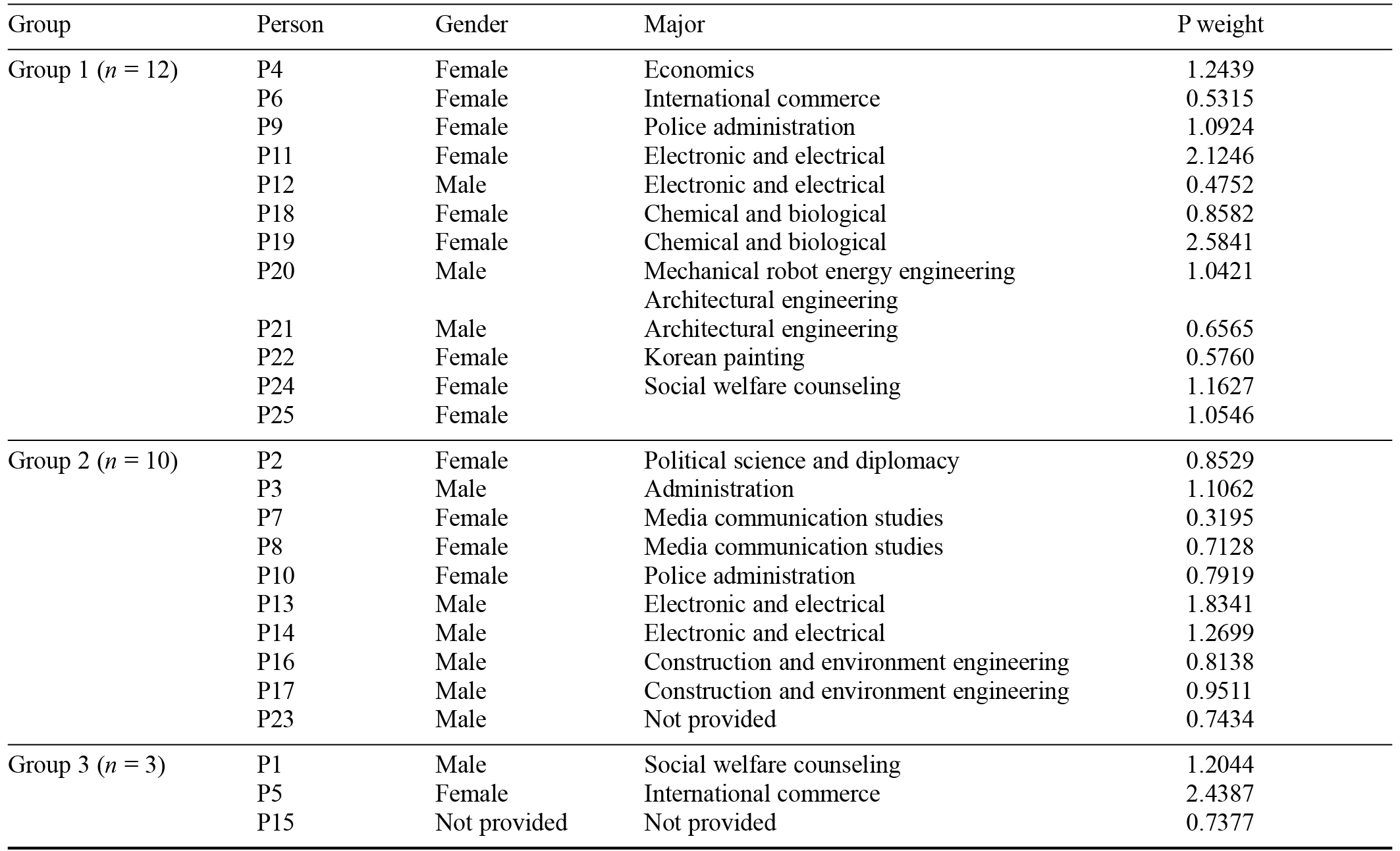

The correlations among the groups indicate their degree of similarity. The correlation between Groups 1 and 2 was .262, that between Groups 1 and 3 was .314, and that between Groups 2 and 3 was .481. Factor weights for each group and participants’ demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. The factor weight was derived from the analysis and indicates how well each participant matches or represents that group.

Table 2. Participants’ Demographic Characteristics and Factor Weights by Group

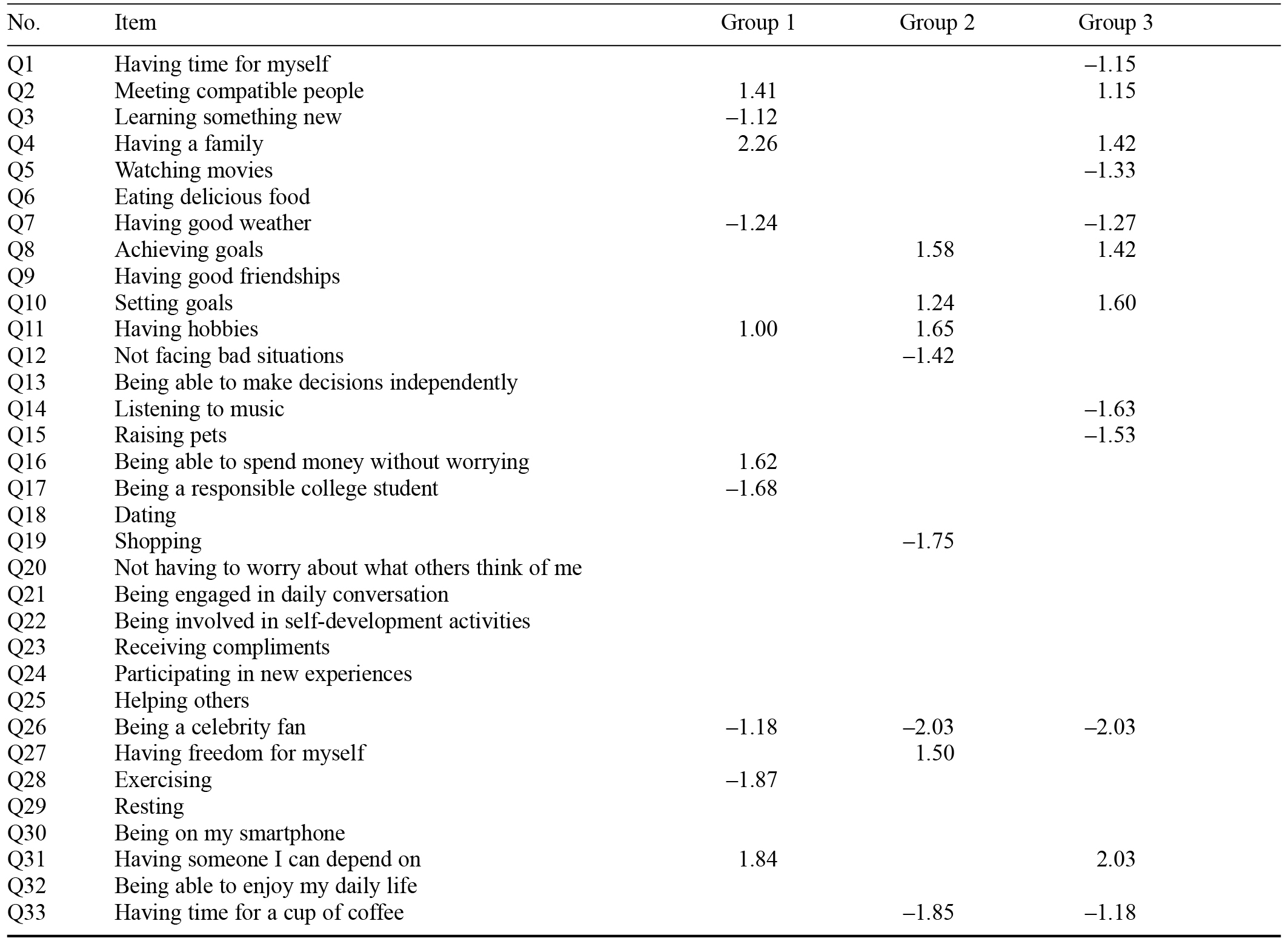

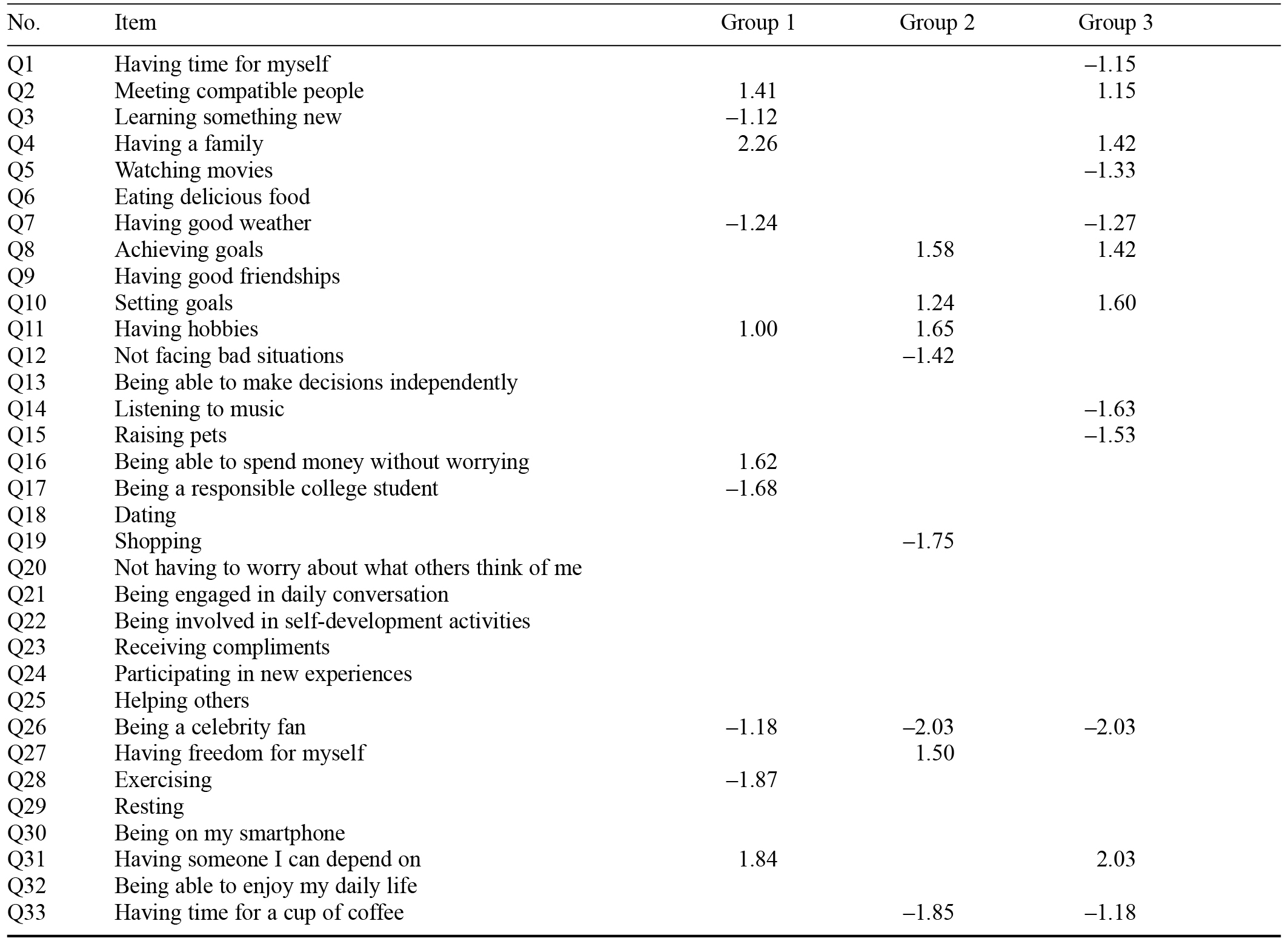

Items in the Q set and the z scores whose absolute values were greater than 1 for each type are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Statements in Q Set and Group z Scores

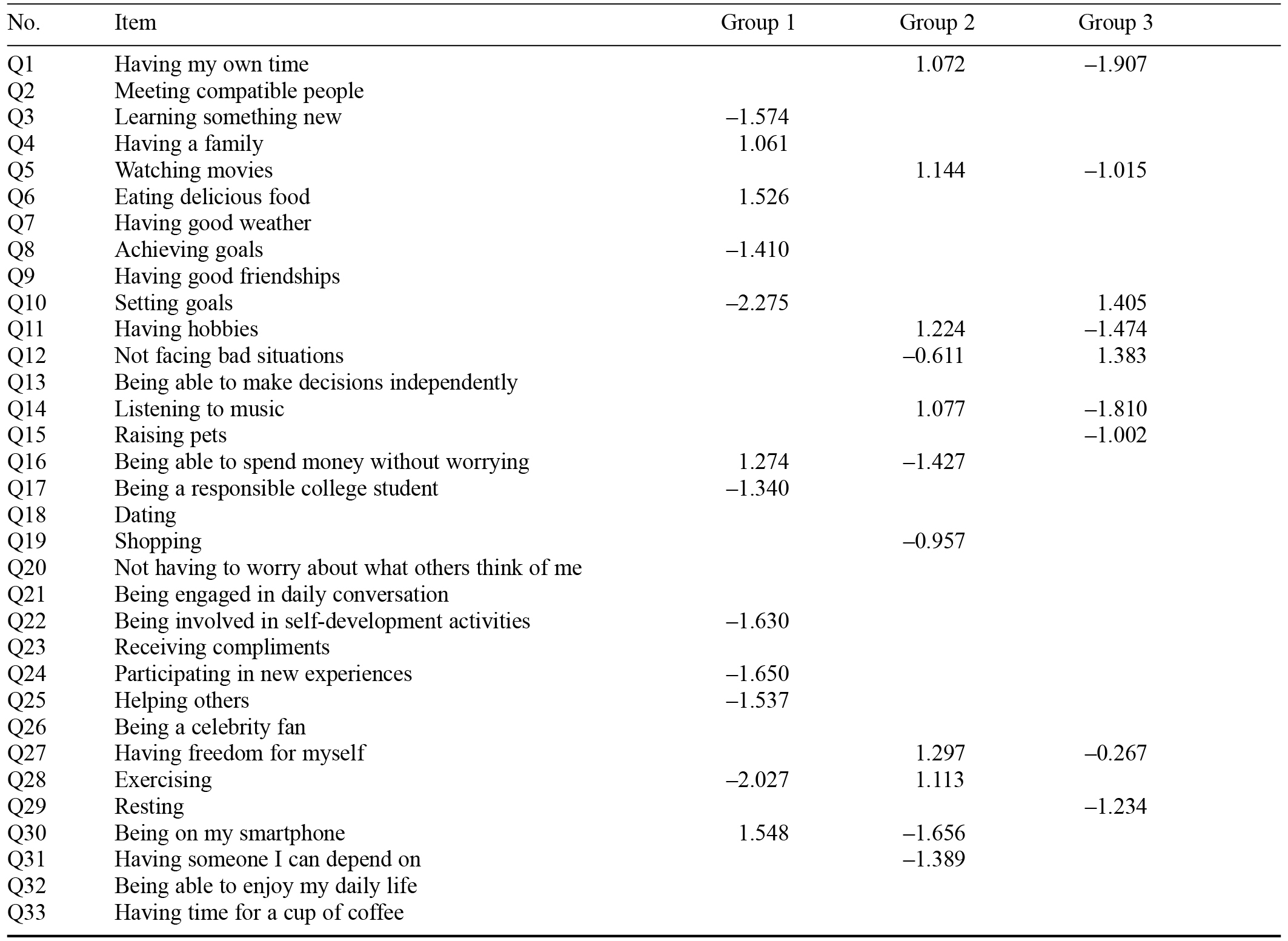

Table 4. Statements with Group Difference Eigenvalues Exceeding One

Characteristics of Groups According to Perceptions of Happiness

Group 1: Happiness Through Everyday Relationships

Items with which participants strongly agreed in Group 1 were “Having a family” (Q4), “Having someone I can depend on” (Q31), and “Meeting compatible people” (Q2). In contrast, these participants strongly disagreed with the items “Exercising” (Q28), “Being responsible as a college student” (Q17), “Having good weather” (Q7), “Being a celebrity fan” (Q26), and “Learning something new” (Q3). Unlike those in the two other groups, participants in this group strongly agreed with “Being on my smartphone” (Q30), “Eating delicious food” (Q6), “Being able to spend money without worrying” (Q16), and “Having a family” (Q4), and strongly disagreed with “Setting goals” (Q10), “Exercising” (Q28), “Participating in new experiences” (Q24), “Being involved in self-development” (Q22), “Learning something new” (Q3), “Helping others” (Q25), “Achieving goals” (Q8), and “Being responsible as a college student” (Q17).

The participant in this group with the highest factor weight (P19) selected Q4 and Q31 as the items with which she most agreed, and Q17 and Q28 as the items with which she most disagreed. Her explanation for these choices was as follows:

|

She also wrote the following:

|

For the Group 1 participants, interpersonal relationships were the main component of their happiness. Specifically, they expressed heavy reliance on family. In addition, they experienced happiness in their daily lives, such as when using their smartphone or eating delicious food, but they did not believe that active participation, such as immersing themselves in activities or achieving goals, constituted happiness.

Group 2: Happiness Through Self-Motivated Experiences

Items with which there were strong agreement in Group 2 were “Having hobbies” (Q11), “Having freedom for myself” (Q27), and “Setting goals” (Q10). Items with which there were strong disagreement were “Being a celebrity fan” (Q26), “Being on my smartphone” (Q30), “Having time for a cup of coffee” (Q33), “Shopping” (Q19), and “Not facing bad situations” (Q12). Unlike those in the two other groups, participants in this group strongly agreed with “Having freedom for myself” (Q27), “Having hobbies” (Q11), “Watching movies” (Q5), “Exercising” (Q28), “Listening to music” (Q14), and “Having my own time” (Q1), and strongly disagreed with “Shopping” (Q19), “Being on my smartphone” (Q30), “Not facing bad situations” (Q12), and “Being able to spend money without worrying” (Q16).

The participant in this group with the highest factor weight (P13) selected Q24 and Q5 as the items with which he agreed the most, and Q19 and Q33 as the items with which he disagreed the most. His explanation for these choices was as follows:

|

Participants in Group 2 perceived leisure activities, such as hobbies, as important in their life. In addition, they assigned meaning to achieving goals and making free choices. However, they did not believe that being able to spend money without worrying would contribute more to their happiness than would having time for personal activities.

Group 3: Happiness Through Setting and Achieving Life Goals

Items with which participants in Group 3 strongly agreed were “Setting goals” (Q10) and “Achieving goals” (Q8). Participants strongly disagreed with items “Being a celebrity fan” (Q26), “Being on my smartphone” (Q30), “Having time for a cup of coffee” (Q33), and “Shopping” (Q19). Unlike those in the other two groups, participants in this group strongly agreed with “Setting goals” (Q10) and “Not facing bad situations” (Q12), and they strongly disagreed with “Having my own time” (Q1), “Listening to music” (Q14), “Having hobbies” (Q11), “Having freedom for myself” (Q27), “Watching movies” (Q5), and “Raising pets” (Q15).

The participant in this group with the highest factor weight (P5), selected Q8 and Q31 as the items with which she most agreed, and Q15 and Q26 as the items with which she most disagreed. Her explanation for these choices was as follows:

|

She also wrote, “Since I have never really liked celebrities passionately, I don’t really sympathize with them. Personally, I am happier to take care of the people I know than to pour that passion on people I don’t know.”

Participants in Group 3 valued the process of setting and achieving goals. Even in the case of personal experiences (e.g., hobbies) they lacked interest in things that did not give them a sense of accomplishment.

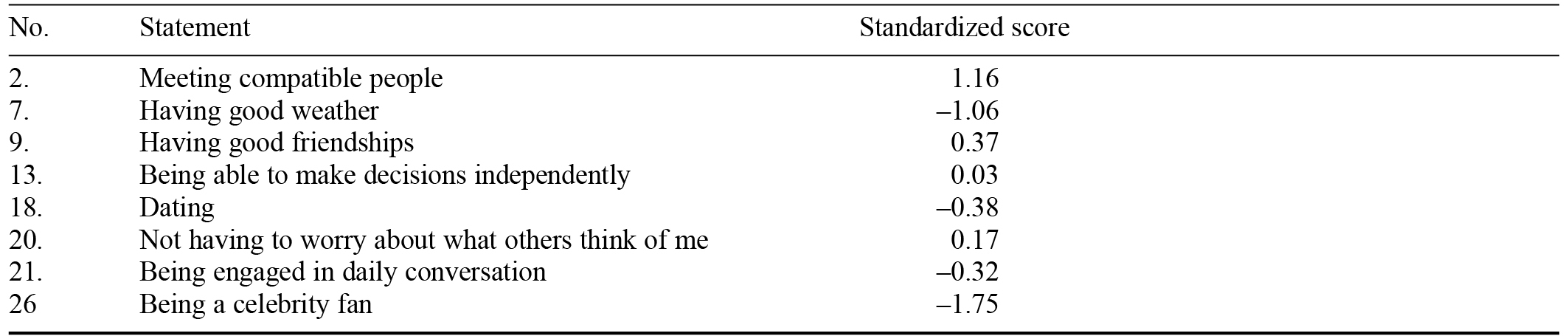

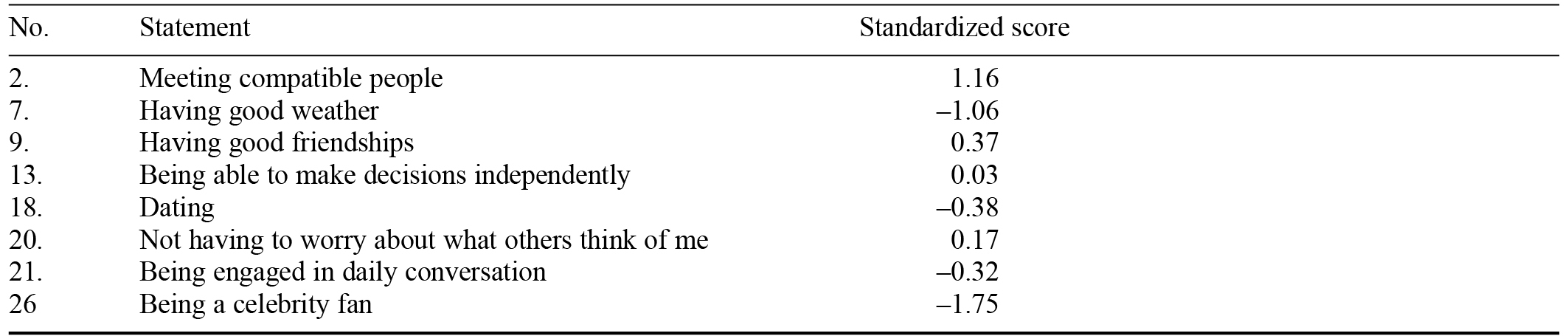

Consensus items refer to those with which all groups agreed. There were eight consensus items in this study (see Table 5).

Table 5. Consensus Items and Their Standardized Scores

Discussion

From our examination of South Korean college freshmen students’ perceptions of happiness during the COVID-19 pandemic, three distinct perceptions of happiness emerged. Relationships were vital for Group 1’s happiness. Previous results have shown that social support in relationships affects college students’ life satisfaction, which supports the characteristics of Group 1 (Jang, 2020; Tarrahi & Nasirian, 2017; Zhou & Lin, 2016). In addition, according to Demir and Davidson (2013), friendship is a powerful predictor of happiness. As such, the psychological experiences associated with interpersonal relationships were particularly meaningful to Group 1. Collective relationships are highly valued in Asian cultures, which strongly influences individual happiness (Haas et al., 2021; Lu & Gilmour, 2004). Perceptions of happiness as identified in Group 1 reflect these characteristics of Asian cultures. Because of COVID-19 social distancing measures, incoming college students spent their first year disconnected from their peers and campus life. Therefore, participants subscribing to the Group 1 view of happiness may have been experiencing difficulty in achieving happiness through human relationships. Opportunities, even via virtual methods, must be provided for them to form relationships and adapt well to college life (Copeland et al., 2021).

Participants in Group 2 regarded freely chosen activities and hobbies as important for their happiness. As Liu and Da (2020) have shown that leisure time is related to happiness, this supports these participants’ characteristics. The importance of participation in physical activity or work to achieve happiness has also been demonstrated (Nawijn & Veenhoven, 2013; Schiffer & Roberts, 2018). However, according to Wei et al. (2015), passive (vs. active) leisure activities contribute more to happiness. Thus, although leisure activities may influence happiness, there is no scholarly consensus on the type of activity. This suggests that researchers, rather than determining the elements of happiness based on the type of leisure activities, should focus on what motivates college students to take part in these activities, which can influence their positive development (Larson, 2000).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, college students experienced few face-to-face leisure activities and were limited to activities such as relaxation and video games (Kang et al., 2020; Park et al., 2020). However, owing to technology advances, the scope of virtual activities has expanded. Ettekal and Agans (2020) suggested innovative ways for college students to enjoy leisure using technology. For example, virtual meetings can be used more innovatively, such as through parallel play, where students engage in similar activities in different places, for example, baking or making art together. Creative ways to meet others during social distancing are also being found.

Participants in Group 3 regarded setting and achieving goals as essential to their happiness. According to Flynn and MacLeod (2015), academic success is related to college students’ happiness, which is consistent with the characteristics of Group 3. Uchida et al. (2004) found in the U.S. cultural context that happiness tends to be defined in terms of personal achievement, whereas in the East Asian cultural context, personal relationships are more important. Thus, there are crucial differences in factors affecting happiness between Eastern and Western cultures (Lu & Gilmour, 2004). However, similar to Group 3, some contemporary South Korean college students view individual achievement as important and believe that goal achievement is a meaningful component of happiness. This result indicates a change in Korean culture and thought (Rowley, 2013).

Further, when participants examined consensus items, each group considered meeting compatible people an important factor in happiness, and disagreed that being a celebrity fan is important for happiness. Thus, Korean college freshmen regarded interpersonal relationships as important, and did not experience happiness if they were not in a direct relationship. Happiness is an area that can be improved with educational programs. According to Smith et al. (2021), attendance at classes in positive psychology tends to improve students’ happiness. Therefore, a variety of happiness-themed programs should be offered at colleges to help incoming students adapt to college life. The developers of these programs must understand subjective characteristics that contribute to the improvement of happiness experience.

Because this study was conducted with South Koreans entering college in 2020, the elements contributing to participants’ happiness may have been subject to social and cultural influences such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Asian cultural values (Kang et al., 2020; Lu & Gilmour, 2004). Therefore, studies on happiness in more generalizable environments are required.

The subjective perceived happiness of South Korean college freshmen differed from person to person. Interpersonal relationships, leisure activities, and goals had a major influence on participants’ achievement of happiness. Our findings contribute to the literature because we have offered suggestions for improving college students’ happiness in general, and presented basic data to develop programs to help freshmen adapt to college life during the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2017). The association between religiosity, generalized self-efficacy, mental health, and happiness in Arab college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 109, 12–16.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.010

Bono, G., Reil, K., & Hescox, J. (2020). Stress and wellbeing in urban college students in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic: Can grit and gratitude help? International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(3), 39–57.

https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i3.1331

Brown, S. R. (1980). Political subjectivity: Application of Q methodology in political science. Yale University Press.

Bum, C.-H., & Jeon, I.-K. (2016). Structural relationships between students’ social support and self-esteem, depression, and happiness. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 44(11), 1761–1774.

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.11.1761

Choi, M., & Cho, S. (2016). Structural analysis of factors influencing university students’ happiness. Journal of Families and Better Life, 34(1), 49–63.

https://doi.org/10.7466/JKHMA.2016.34.1.49

Cloninger, C. R., & Zohar, A. H. (2011). Personality and the perception of health and happiness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 128(1–2), 24–32.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.012

Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z., Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., … Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 134–141.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466

Demir, M., & Davidson, I. (2013). Toward a better understanding of the relationship between friendship and happiness: Perceived responses to capitalization attempts, feelings of mattering, and satisfaction of basic psychological needs in same-sex best friendships as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 525–550.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9341-7

Demirtaş, A. S. (2020). Optimism and happiness in undergraduate students: Cognitive flexibility and adjustment to university life as mediators. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 36(2), 320–329.

https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.381181

Economos, C. D., Hildebrandt, M. L., & Hyatt, R. R. (2008). College freshman stress and weight change: Differences by gender. American Journal of Health Behavior, 32(1), 16–25.

https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.32.1.2

Ettekal, A. V., & Agans, J. P. (2020). Positive youth development through leisure: Confronting the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth Development, 15(2), 1–20.

https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2020.962

Flynn, D. M., & MacLeod, S. (2015). Determinants of happiness in undergraduate university students. College Student Journal, 49(3), 452–460.

Gupta, A., Jagzape, A., & Kumar, M. (2021). Social media effects among freshman medical students during COVID-19 lock-down: An online mixed research. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10, Article e55.

https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_749_20

Haas, B. W., Hoeft, F., & Omura, K. (2021). The role of culture on the link between worldviews on nature and psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 170, Article e110336.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110336

Herrington, N., & Coogan, J. (2011). Q methodology: An overview. Research in Teacher Education, 1(2), 24–28.

https://doi.org/10.15123/uel.8604v

Hylton, P., Kisby, B., & Goddard, P. (2018). Young people’s citizen identities: A Q-methodological analysis of English youth perceptions of citizenship in Britain. Societies, 8(4), 1–21.

https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8040121

Jang, I. (2020). Factors influencing the effect of subjective happiness on the perceived stress and faith maturity of Christian university freshman [In Korean]. Journal of the Korean Applied Science and Technology, 37(2), 328–339.

https://doi.org/10.12925/jkocs.2020.37.2.328

Jeong, J.-N. (2018). An exploratory study of the stress coping strategies of university students: Utilizing photovoice methodology [In Korean]. Journal of Digital Convergence, 16(10), 545–555.

https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2018.16.10.545

Jo, G. Y., & Park, H. S. (2019). The effects of the ‘Becoming Happy I’ program on gratitude disposition, self-esteem, flow, and subjective happiness in nursing college students [In Korean]. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 362–372. https://bit.ly/3icSD7Q

Joodat, A. S., & Zarbakhsh, M. (2015). Adaptation to college and interpersonal forgiveness and the happiness among the university students. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 3(4), 243–250. https://bit.ly/2VpF3EY

Kang, J. H., Bak, A. R., & Han, S. T. (2020). A phenomenological study of the lifestyle change experiences of undergraduates due to COVID-19 [In Korean]. Journal of the Korea Entertainment Industry Association, 14(5), 289–297.

https://doi.org/10.21184/jkeia.2020.7.14.5.289

Karaşar, B., & Baytemir, K. (2018). Need for social approval and happiness in college students: The mediation role of social anxiety. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(5), 919–927.

https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.060513

Kecojevic, A., Basch, C. H., Sullivan, M., & Davi, N. K. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on mental health of undergraduate students in New Jersey, cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 15(9), Article e0239696.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239696

Kim, H. K. (2008). Q methodology: Philosophy, theories, analysis, and application. Communication Books.

Kim, K., & Lim, J. (2012). Effects of optimism and orientation toward happiness on the psychological well-being of college students [In Korean]. Journal of the Korean Home Economics Association, 50(1), 89–101.

https://doi.org/10.6115/khea.2012.50.1.089

Kim, K. H., & Kang, S. B. (2016). Development and validation of the College Life Adjustment Scale for University Freshmen [In Korean]. Korean Journal of General Education, 10(3), 253–293. https://bit.ly/2V8ly49

Koçak, R. (2008). The effects of cooperative learning on psychological and social traits among undergraduate students. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 36(6), 771–782.

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.6.771

Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55(1), 170–183.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170

Liu, H., & Da, S. (2020). The relationships between leisure and happiness-A graphic elicitation method. Leisure Studies, 39(1), 111–130.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1575459

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented SWB. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 269–291.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8789-5

Nawijn, J., & Veenhoven, R. (2013). Happiness through leisure. In T. Freire (Ed.), Positive leisure science: From subjective experience to social contexts (pp. 193–209). Springer Science+Business Media.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5058-6_11

Park, K.-H., Lee, S.-Y., & Kim, J.-W. (2020). COVID-19 postwar leisure changes in university students and their relationship to leisure dynamics and health beliefs [In Korean]. Korean Journal of Leisure, Recreation & Park, 44(3), 66–86.

https://doi.org/10.26446/kjlrp.2020.9.44.3.69

Peltzer, K., & Pengpid, S. (2013). Subjective happiness and health behavior among a sample of university students in India. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 41(6), 1045–1056.

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.6.1045

Rager, L. E. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on recruitment, enrollment, and freshman expectations in higher education [Published master’s thesis]. Youngstown State University, OH, USA. OhioLINK Electronic Theses Dissertations Center. https://bit.ly/3CfAL4e

Rowley, C. (2013). The changing nature of management and culture in South Korea. In M. Warner (Ed.), Managing across diverse cultures in East Asia: Issues and challenges in a changing globalized world (pp. 122–150). Routledge.

Schiffer, L. P., & Roberts, T.-A. (2018). The paradox of happiness: Why are we not doing what we know makes us happy? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(3), 252–259.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1279209

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. In M. Csikszentmihalyi & R. Larson (Eds.), Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 279–298). Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_18

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

Smith, B. W., Ford, C. G., Erickson, K., & Guzman, A. (2021). The effects of a character strength focused positive psychology course on undergraduate happiness and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(1), 343–362.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00233-9

Tarrahi, M. J., & Nasirian, M. (2017). Happiness and risk behaviours in freshman students of Khorramabad Universities. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 11(2), Article e7345.

https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.7345

Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Kitayama, S. (2004). Cultural constructions of happiness: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 223–239.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8785-9

Wang, X., Hegde, S., Son, C., Keller, B., Smith, A., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), Article e22817.

https://doi.org/10.2196/22817

Wei, X., Huang, S., Stodolska, M., & Yu, Y. (2015). Leisure time, leisure activities, and happiness in China: Evidence from a national survey. Journal of Leisure Research, 47(5), 556–576.

https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2015-v47-i5-6120

Xu, Y.-Y., Wu, T., Yu, Y.-J., & Li, M. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of well-being therapy to promote adaptation and alleviate emotional distress among medical freshmen. BMC Medical Education, 19, Article e182.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1616-9

Zhang, H., & Dai, B. (2018). The intervention effect of writing expression on the well-being of college freshmen [In Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology, 26(9), 1383–1386. https://bit.ly/3xjahuE

Zhang, R.-P. (2016). Positive affect and self-efficacy as mediators between personality and life satisfaction in Chinese college freshmen. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 2007–2021.

https://doi.org/10.1007/S10902-015-9682-0

Zhou, M., & Lin, W. (2016). Adaptability and life satisfaction: The moderating role of social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article e1134.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01134

Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Lester, D. (2017). The association between religiosity, generalized self-efficacy, mental health, and happiness in Arab college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 109, 12–16.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.010

Bono, G., Reil, K., & Hescox, J. (2020). Stress and wellbeing in urban college students in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic: Can grit and gratitude help? International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(3), 39–57.

https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i3.1331

Brown, S. R. (1980). Political subjectivity: Application of Q methodology in political science. Yale University Press.

Bum, C.-H., & Jeon, I.-K. (2016). Structural relationships between students’ social support and self-esteem, depression, and happiness. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 44(11), 1761–1774.

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.11.1761

Choi, M., & Cho, S. (2016). Structural analysis of factors influencing university students’ happiness. Journal of Families and Better Life, 34(1), 49–63.

https://doi.org/10.7466/JKHMA.2016.34.1.49

Cloninger, C. R., & Zohar, A. H. (2011). Personality and the perception of health and happiness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 128(1–2), 24–32.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.012

Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z., Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., … Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 134–141.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466

Demir, M., & Davidson, I. (2013). Toward a better understanding of the relationship between friendship and happiness: Perceived responses to capitalization attempts, feelings of mattering, and satisfaction of basic psychological needs in same-sex best friendships as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2), 525–550.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9341-7

Demirtaş, A. S. (2020). Optimism and happiness in undergraduate students: Cognitive flexibility and adjustment to university life as mediators. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 36(2), 320–329.

https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.381181

Economos, C. D., Hildebrandt, M. L., & Hyatt, R. R. (2008). College freshman stress and weight change: Differences by gender. American Journal of Health Behavior, 32(1), 16–25.

https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.32.1.2

Ettekal, A. V., & Agans, J. P. (2020). Positive youth development through leisure: Confronting the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth Development, 15(2), 1–20.

https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2020.962

Flynn, D. M., & MacLeod, S. (2015). Determinants of happiness in undergraduate university students. College Student Journal, 49(3), 452–460.

Gupta, A., Jagzape, A., & Kumar, M. (2021). Social media effects among freshman medical students during COVID-19 lock-down: An online mixed research. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10, Article e55.

https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_749_20

Haas, B. W., Hoeft, F., & Omura, K. (2021). The role of culture on the link between worldviews on nature and psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 170, Article e110336.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110336

Herrington, N., & Coogan, J. (2011). Q methodology: An overview. Research in Teacher Education, 1(2), 24–28.

https://doi.org/10.15123/uel.8604v

Hylton, P., Kisby, B., & Goddard, P. (2018). Young people’s citizen identities: A Q-methodological analysis of English youth perceptions of citizenship in Britain. Societies, 8(4), 1–21.

https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8040121

Jang, I. (2020). Factors influencing the effect of subjective happiness on the perceived stress and faith maturity of Christian university freshman [In Korean]. Journal of the Korean Applied Science and Technology, 37(2), 328–339.

https://doi.org/10.12925/jkocs.2020.37.2.328

Jeong, J.-N. (2018). An exploratory study of the stress coping strategies of university students: Utilizing photovoice methodology [In Korean]. Journal of Digital Convergence, 16(10), 545–555.

https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2018.16.10.545

Jo, G. Y., & Park, H. S. (2019). The effects of the ‘Becoming Happy I’ program on gratitude disposition, self-esteem, flow, and subjective happiness in nursing college students [In Korean]. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 362–372. https://bit.ly/3icSD7Q

Joodat, A. S., & Zarbakhsh, M. (2015). Adaptation to college and interpersonal forgiveness and the happiness among the university students. Practice in Clinical Psychology, 3(4), 243–250. https://bit.ly/2VpF3EY

Kang, J. H., Bak, A. R., & Han, S. T. (2020). A phenomenological study of the lifestyle change experiences of undergraduates due to COVID-19 [In Korean]. Journal of the Korea Entertainment Industry Association, 14(5), 289–297.

https://doi.org/10.21184/jkeia.2020.7.14.5.289

Karaşar, B., & Baytemir, K. (2018). Need for social approval and happiness in college students: The mediation role of social anxiety. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(5), 919–927.

https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.060513

Kecojevic, A., Basch, C. H., Sullivan, M., & Davi, N. K. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on mental health of undergraduate students in New Jersey, cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 15(9), Article e0239696.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239696

Kim, H. K. (2008). Q methodology: Philosophy, theories, analysis, and application. Communication Books.

Kim, K., & Lim, J. (2012). Effects of optimism and orientation toward happiness on the psychological well-being of college students [In Korean]. Journal of the Korean Home Economics Association, 50(1), 89–101.

https://doi.org/10.6115/khea.2012.50.1.089

Kim, K. H., & Kang, S. B. (2016). Development and validation of the College Life Adjustment Scale for University Freshmen [In Korean]. Korean Journal of General Education, 10(3), 253–293. https://bit.ly/2V8ly49

Koçak, R. (2008). The effects of cooperative learning on psychological and social traits among undergraduate students. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 36(6), 771–782.

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.6.771

Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55(1), 170–183.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170

Liu, H., & Da, S. (2020). The relationships between leisure and happiness-A graphic elicitation method. Leisure Studies, 39(1), 111–130.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1575459

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented SWB. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 269–291.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8789-5

Nawijn, J., & Veenhoven, R. (2013). Happiness through leisure. In T. Freire (Ed.), Positive leisure science: From subjective experience to social contexts (pp. 193–209). Springer Science+Business Media.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5058-6_11

Park, K.-H., Lee, S.-Y., & Kim, J.-W. (2020). COVID-19 postwar leisure changes in university students and their relationship to leisure dynamics and health beliefs [In Korean]. Korean Journal of Leisure, Recreation & Park, 44(3), 66–86.

https://doi.org/10.26446/kjlrp.2020.9.44.3.69

Peltzer, K., & Pengpid, S. (2013). Subjective happiness and health behavior among a sample of university students in India. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 41(6), 1045–1056.

https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.6.1045

Rager, L. E. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on recruitment, enrollment, and freshman expectations in higher education [Published master’s thesis]. Youngstown State University, OH, USA. OhioLINK Electronic Theses Dissertations Center. https://bit.ly/3CfAL4e

Rowley, C. (2013). The changing nature of management and culture in South Korea. In M. Warner (Ed.), Managing across diverse cultures in East Asia: Issues and challenges in a changing globalized world (pp. 122–150). Routledge.

Schiffer, L. P., & Roberts, T.-A. (2018). The paradox of happiness: Why are we not doing what we know makes us happy? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(3), 252–259.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1279209

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. In M. Csikszentmihalyi & R. Larson (Eds.), Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 279–298). Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_18

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

Smith, B. W., Ford, C. G., Erickson, K., & Guzman, A. (2021). The effects of a character strength focused positive psychology course on undergraduate happiness and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(1), 343–362.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00233-9

Tarrahi, M. J., & Nasirian, M. (2017). Happiness and risk behaviours in freshman students of Khorramabad Universities. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 11(2), Article e7345.

https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.7345

Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Kitayama, S. (2004). Cultural constructions of happiness: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 223–239.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8785-9

Wang, X., Hegde, S., Son, C., Keller, B., Smith, A., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), Article e22817.

https://doi.org/10.2196/22817

Wei, X., Huang, S., Stodolska, M., & Yu, Y. (2015). Leisure time, leisure activities, and happiness in China: Evidence from a national survey. Journal of Leisure Research, 47(5), 556–576.

https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2015-v47-i5-6120

Xu, Y.-Y., Wu, T., Yu, Y.-J., & Li, M. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of well-being therapy to promote adaptation and alleviate emotional distress among medical freshmen. BMC Medical Education, 19, Article e182.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1616-9

Zhang, H., & Dai, B. (2018). The intervention effect of writing expression on the well-being of college freshmen [In Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology, 26(9), 1383–1386. https://bit.ly/3xjahuE

Zhang, R.-P. (2016). Positive affect and self-efficacy as mediators between personality and life satisfaction in Chinese college freshmen. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 2007–2021.

https://doi.org/10.1007/S10902-015-9682-0

Zhou, M., & Lin, W. (2016). Adaptability and life satisfaction: The moderating role of social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article e1134.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01134

Figure 1. Research Process

Table 1. Eigenvalues and Explanatory Variance of Perceptions According to Group

Table 2. Participants’ Demographic Characteristics and Factor Weights by Group

Table 3. Statements in Q Set and Group z Scores

Table 4. Statements with Group Difference Eigenvalues Exceeding One

Table 5. Consensus Items and Their Standardized Scores

Song Yi Lee, Dharma College, Dongguk University-Seoul, 30 Pildong-ro 1 gil, Jung-gu, 0462, Seoul 100-715, Republic of Korea. Email: [email protected]