The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic was an unprecedented event in history (Venkatesh, 2020). This global shock has had a significant impact on organizations. For instance, to ensure the normal operation of a company and limit the spread of the virus, organizations adopted measures such as downsizing (Dahmani & Gasmi, 2022) and mergers (Bauer et al., 2022). Simultaneously, as employee work changes are highly related to organizational restructuring (Han et al., 2023), during the pandemic, employees were forced to adapt quickly to flexible work arrangements, such as company relocation, remote working, and self-isolation (Ambrogio et al., 2022; Loretto et al., 2010). Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic instigated substantial alterations in the workplace environment for many employees and potentially influenced their behavior.

Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, many individuals actively sought personal work development, including searching for job-related information and exploring other employment opportunities, yet this area remains largely unexplored and warrants further investigation. In addition, the focus in existing research on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employee information-seeking and job-seeking behavior has been primarily on the event itself (McFarland et al., 2020; Pan & Zhang, 2020), and its potential impact mechanisms are yet to be revealed. Moreover, given that multiple factors influence individual behavior in the workplace (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978), it remains unclear whether the relationship between work changes and employee job-related behaviors varies across different environmental characteristics or psychological circumstances.

To better understand the relationship between COVID-19-related work changes and employees’ proactive work behaviors, we constructed an intermediary moderation model based on affective events theory (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996), in which it is posited that work events are the direct cause of emotional reactions, which, in turn, influence individuals’ judgment and drive their behavior. Hence, we chose job insecurity as the mediating condition to explain the process of the relationship between COVID-19-related work changes and employees’ proactive work behaviors.

Job insecurity can be described as an emotional state characterized by employees’ apprehension about the stability of their employment and the threat of job loss (Grunberg et al., 2006). In this context we hypothesized that the significant work changes brought about by COVID-19 led to employees perceiving their jobs as unstable and at risk. Additionally, we identified employees’ work-related information seeking and job-seeking behaviors as indicators of proactive work behaviors, as both are active approaches employees take for their own development. In the context of the workplace, information seeking is the process of an individual actively seeking information about the organization (Brown et al., 2001), and job-seeking behavior refers to the specific actions and behaviors that individuals engage in when searching for employment (Schmit et al., 1993; Wanberg et al., 1996). According to affective events theory, when COVID-19-related work changes lead to job insecurity, employees become concerned about job stability and the potential of being laid off, and may engage in job-seeking behaviors as a means of personal development.

Moreover, affective events theory suggests that job characteristics can moderate the impact of work-related emotions and attitudes on judgment-driven behaviors (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Therefore, we incorporated job embeddedness as a job characteristic, which is a composite force consisting of contextual and perceptual factors that deter individuals from leaving their current employment (T. Lee et al., 2014; Yao et al., 2004). It is a structure composed of situational and perceptual forces that connect individuals to their workplace, involving the location, people, and issues within their job (Yao et al., 2004). This job characteristic reflects employees’ tendency to stay within an organization (Crossley et al., 2007). Therefore, we believed that understanding job embeddedness would be crucial in the context of work changes related to COVID-19, as it can determine whether employees will stay and adapt or will seek new opportunities in uncertain and insecure situations. In summary, we anticipated that varying degrees of job embeddedness would differentially influence the relationship between COVID-19-related work changes and employees’ proactive work behaviors. Our conceptual model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Theoretical Model

COVID-19-Related Work Changes and Job Insecurity

The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic exerted a profound impact on various aspects of the resources of countries around the world, including public health, healthcare, the economy, and the labor market (Venkatesh, 2020). Various industries, in an effort to alleviate the impact of the pandemic, compelled employees to make flexible adjustments (X. Liu et al., 2023), enabling survival in an environment of business downturn. This involved, for instance, embracing telecommuting practices or restructuring various workflow models and modes of interaction among coworkers, along with altering how employees engaged with customers at physical venues (Mihalache & Mihalache, 2022). Concurrently, the existing literature suggests that such changes in work conditions could impact the mental health of employees (W. Liu et al., 2021). To better elucidate the psychological and emotional responses of employees in this work scenario, we selected a particularly critical psychological factor: job insecurity. According to affective events theory, we believed that COVID-19-related work changes would contribute to the emergence of job insecurity. The pandemic had a significant impact on businesses, with many companies and organizations facing the risk of supply-and-demand disruptions (Sombultawee et al., 2022), leading to substantial layoffs of staff (Blustein et al., 2020). This posed a threat of unemployment to the employees, thereby causing job insecurity among the staff (De Cuyper et al., 2010). Furthermore, as the pandemic spread, employees transitioned from previously safe working conditions to an environment with a risk of infection (Blustein et al., 2020). This shift from a traditionally secure work environment to one that was rapidly changing and insecure may have increased employees’ job insecurity (Blackmore & Kuntz, 2011). During the pandemic, employees had to persevere and adapt to a tense working environment, volatile work schedules, and unfamiliar job characteristics (Mihalache & Mihalache, 2022), which may have led to psychological anxiety and stress, thereby causing employees to have concerns about the continuity and stability of their employment. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: COVID-19-related work changes will be positively related to employees’ job insecurity.

Job Insecurity, Work-Related Information Seeking, and Job-Seeking Behavior

Information seeking includes seven components: overt questions, indirect questions, use of third parties, testing limits, disguised conversations, observing, and surveillance (Miller & Jahlin, 1991). In the context of employees’ work this manifests as acquiring work-related information through means such as consulting supervisors, experienced colleagues, and other employees, as well as referring to written documents (Wolfe Morrison, 1993). Researchers have previously found that employees’ behavior is often influenced by their emotions (Lazarus, 1991). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced additional psychological, social, and occupational demands, potentially altering employees’ attitude toward their work (Mihalache & Mihalache, 2022). Consequently, when employees experience panic because of job instability and unsustainability, they seek methods to cope with this predicament.

Using affective events theory, we proposed that in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, employees’ sense of job insecurity would promote their work-related information seeking. Research has indicated that the inherent uncertainty associated with experiencing job insecurity prevents employees from using effective and appropriate coping strategies in the workplace (Sverke et al., 2002). Consequently, they engage in work-related information seeking to resolve their own confusion. Ashford et al. (1989) suggested that job insecurity may lead to a decline in job performance; therefore, when employees face the risk of decreased performance, they may seek information for assistance. Additionally, in the circumstance of the COVID-19 pandemic, employees’ sense of insecurity also stemmed from concerns about their occupational health (Venkatesh, 2020). In such circumstances, employees actively seek protective measures and information about local epidemic policies to ensure their health and the normal progression of their work. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a: Job insecurity will be positively related to employees’ work-related information seeking.

Job-seeking behavior is also an important means of coping with changes in the workplace (Schmit et al., 1993). Similarly, job insecurity can affect employees’ willingness to stay in the organization (Astarlioglu et al., 2011). When individuals feel insecure in their work, they are less likely to remain with the organization, which can lead to them engaging in job-seeking behavior. Following affective events theory, we believed that job insecurity would promote employees’ job-seeking behavior. First, job insecurity involves internal stressors such as fear and anxiety (Ashford et al., 1989), and employees experiencing work insecurity are inevitably driven to behaviors that have the goal of finding new employment. Second, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered large-scale layoffs of staff, which incited panic among employees about job instability (Blustein et al., 2020; Lian et al., 2022). Thus, when employees continually see their colleagues being laid off, they may take the initiative to seek backup plans for themselves. Third, because of concerns about their own physical health, employees might consider switching to a relatively safer job. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2b: Job insecurity will be positively related to employees’ job-seeking behavior.

The Moderating Role of Job Embeddedness

Job embeddedness has been conceptualized as a combination of two subfactors: on-the-job embeddedness and off-the-job embeddedness (Mitchell et al., 2001). On-the-job embeddedness concerns the level of individuals’ entanglement within their workplace, whereas the focus in off-the-job embeddedness is on the extent of people’s integration into their community. Each type of embeddedness comprises three foundational elements: the formal or informal ties between an individual and institutions, places, or other individuals, which are termed links; fit, which is the congruence or ease employees experience within their work and nonwork settings; and the potential loss of material or psychological advantages that could result from exiting one’s job or community, that is, employees’ sense of sacrifice.

Wheeler et al. (2012) found that job embeddedness motivates, guides, and sustains behavior. When employees have a high degree of job embeddedness, they are more likely to remain within the organization, thereby prompting them to compensate for any deficiencies. Drawing on affective events theory, we proposed that job embeddedness would amplify the positive correlation between job insecurity and work-related information seeking. First, studies have indicated that a high level of job embeddedness among employees reflects positive organizational commitment (T. Lee et al., 2014). Therefore, when feelings of job insecurity arise, employees with high job embeddedness will actively seek work-related information to ensure their retention within the organization. Second, Halbesleben and Wheeler (2008) found that job embeddedness can yield additional resources within the workplace. This includes improved access to advice or work assistance; hence, compared with their colleagues, those employees with higher levels of embeddedness may exhibit increased information-seeking behavior. Third, during the COVID-19 pandemic, if employees were compelled to remain within an organization, this process would inevitably lead to their insecurity, subsequently causing them to do everything possible to seek useful and relevant information. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Job embeddedness will moderate the positive relationship between job insecurity and work-related information seeking, such that this relationship will be stronger when employees’ job embeddedness is high (vs. low).

Unlike information seeking, which suggests a desire to remain within an organization, job-seeking behavior indicates an employee’s intention to leave. Hence, we posited that job embeddedness would mitigate the positive correlation between job insecurity and job-seeking behavior. First, job embeddedness often represents a state of inertia as, most of the time, staying in one’s current employment is not even regarded as a choice process (Mitchell & Lee, 2001). For instance, social factors such as familial responsibilities may lead to a high degree of job embeddedness (e.g., because of economic considerations). As a result, even though a sense of insecurity among employees may prompt job-seeking behavior, this action is often brought to a halt because of consideration for their family. Second, as previously described, high job embeddedness implies that employees have established strong social and emotional ties with their colleagues and the organization (T. Lee et al., 2014). Even when employees are faced with job insecurity, these robust social connections and loyalty to the organization may incline them to stay in their current position rather than seeking new job opportunities. Third, job embeddedness is often associated with the investments employees and organizations have made in employees’ current role (Hom et al., 2009). A higher level of job embeddedness implies greater investment. Consequently, even if employees with high levels of embeddedness feel job insecurity, the potential loss of their investment may become a factor in their reluctance to seek new employment opportunities. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Job embeddedness will moderate the positive relationship between employees’ job insecurity and job-seeking behavior, such that this relationship will be weaker when job embeddedness is high (vs. low).

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample for this study was drawn from companies in Sichuan, Shandong, Jiangsu, and Anhui Provinces in China, with employees working in various sectors including accommodation and catering, manufacturing, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and wholesale and retail industries. We began our research in October 2022, after the occurrence of a regional COVID-19 outbreak in the country. To comply with epidemic prevention policies, we utilized an online survey for data collection. Before the survey began, we communicated our research design and objectives to the participants, assuring them of the confidentiality and anonymity of the survey. To decrease the likelihood of duplication, we utilized a technique that limited the use of multiple devices for respondents, guaranteeing that each participant filled out the survey just once. After rigorous screening by our team, we obtained 571 valid responses.

The sample comprised 266 men (46.6%) and 305 women (53.4%). Regarding age, six participants (1.1%) were aged under 18 years, 88 (15.4%) were aged 18–25 years, 143 (25%) were aged 26–35 years, 171 (29.9%) were aged 36–45 years, 152 (26.6%) were aged 46–55 years, and 11 (1.9%) were aged 56 years or over. In terms of educational attainment, 64 (11.2%) had finished their schooling at junior high school or below, 141 (24.7%) had a high school diploma, 157 (27.5%) held an associate degree, 132 (23.1%) had a bachelor’s degree, and 77 (13.5%) had a master’s degree or higher. Concerning tenure with their company, 77 (13.5%) had been with the company for 0–1 years, 127 (22.2%) for 1–2 years, 129 (22.6%) for 2–3 years, 109 (19.1%) for 3–5 years, 66 (11.6%) for 5–10 years, and 63 (11%) for 10 years or more.

Measures

The scales were originally composed in English; thus, we arranged to translate them into Chinese using back-translation (Brislin, 1980). We invited two assistant professors in management to conduct the back-translation. Unless otherwise specified, items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much or 1 = never to 5 = always).

COVID-19-Related Work Changes

We employed the eight-item scale developed by Madero Gómez et al. (2020) to measure employees’ perception regarding the impact of COVID-19 on their work. A sample item is “The coronavirus has put the operations of my workplace at risk.” Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .92.

Job Insecurity

We drew on the four-item scale developed by Schreurs et al. (2012) to measure employees’ job insecurity. A sample item is “I fear that I might lose my job.” Cronbach’s alpha was .87 in our study.

Work-Related Information Seeking

We used the seven-item scale developed by Wolfe Morrison (1993) to measure employees’ information-seeking behavior. A sample item is “I will ask my immediate supervisor for help.” Cronbach’s alpha in our study was .92.

Job-Seeking Behavior

We adapted a 12-item scale developed by Blau (1994) to measure employees’ job-seeking behavior. A sample item is “I have sent my résumé to potential employers.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .98 in our study.

Job Embeddedness

We measured job embeddedness with the seven-item scale developed by Crossley et al. (2007). A sample item is “I feel attached to this organization.” Cronbach’s alpha in our study was .97.

Control Variables

To ensure the robustness of our study, we considered various characteristics of the respondents. We controlled for gender, age, educational level, and organizational tenure to mitigate any potential impact of these demographic data on the survey results.

Data Analysis

We used SPSS 27.0 and Mplus 8.3 for data processing and analysis.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

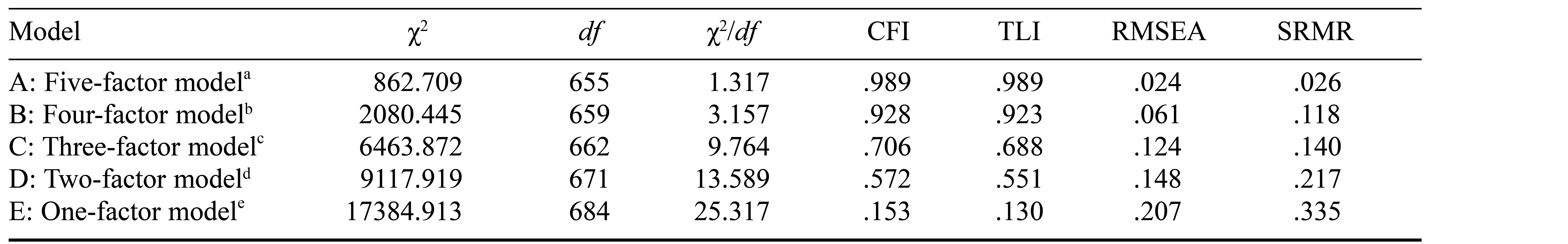

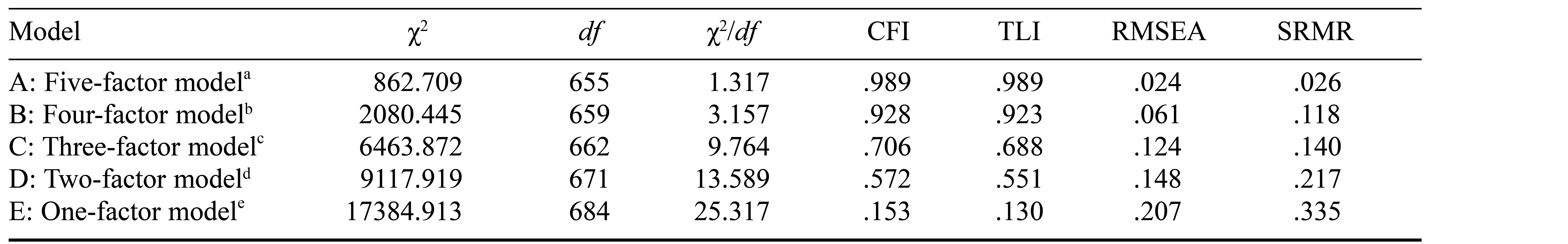

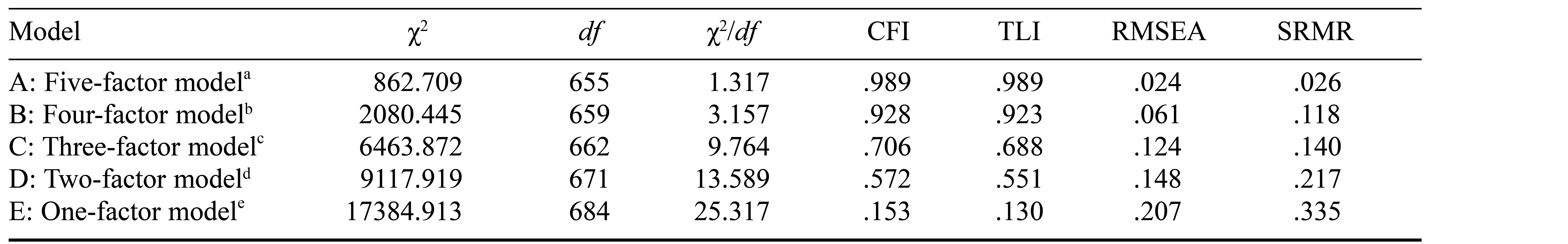

As depicted in Table 1, the five-factor model demonstrated an excellent fit to the data, outperforming the alternative competing models in the confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Note. N = 571. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root-mean-square residual.

a COVID-19-related work changes, Job insecurity, Work-related information seeking, Job-seeking behavior, Job embeddedness; b COVID-19-related work changes, Job insecurity, Work-related information seeking, Job-seeking behavior + Job embeddedness; c COVID-19-related work changes + Job insecurity + Job embeddedness, Job-seeking behavior, Work-related information seeking; d COVID-19-related work changes + Job insecurity + Work-related information seeking + Job embeddedness, Job-seeking behavior; e COVID-19-related work changes + Job insecurity + Work-related information seeking + Job-seeking behavior + Job embeddedness.

*** p < .001.

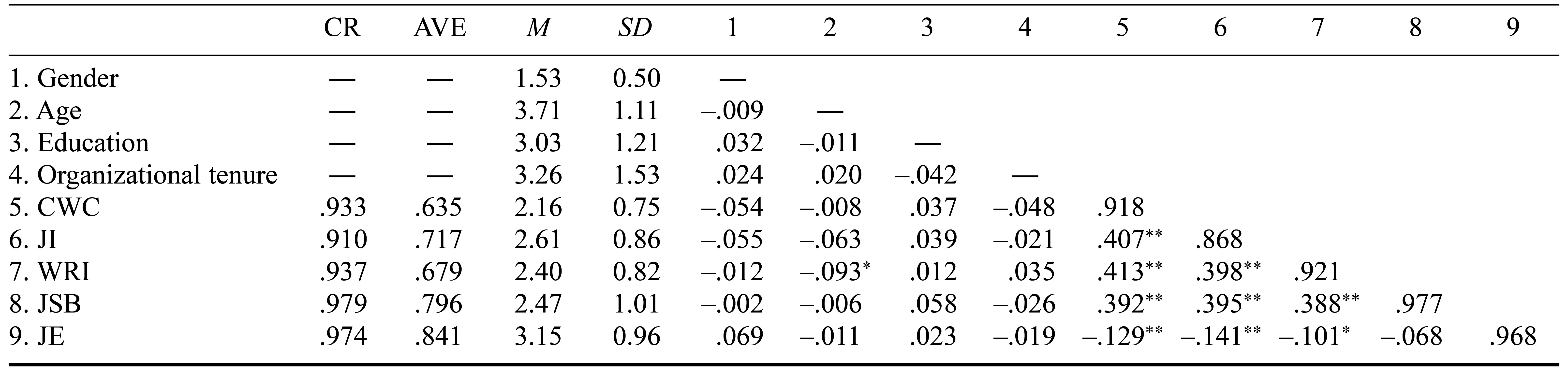

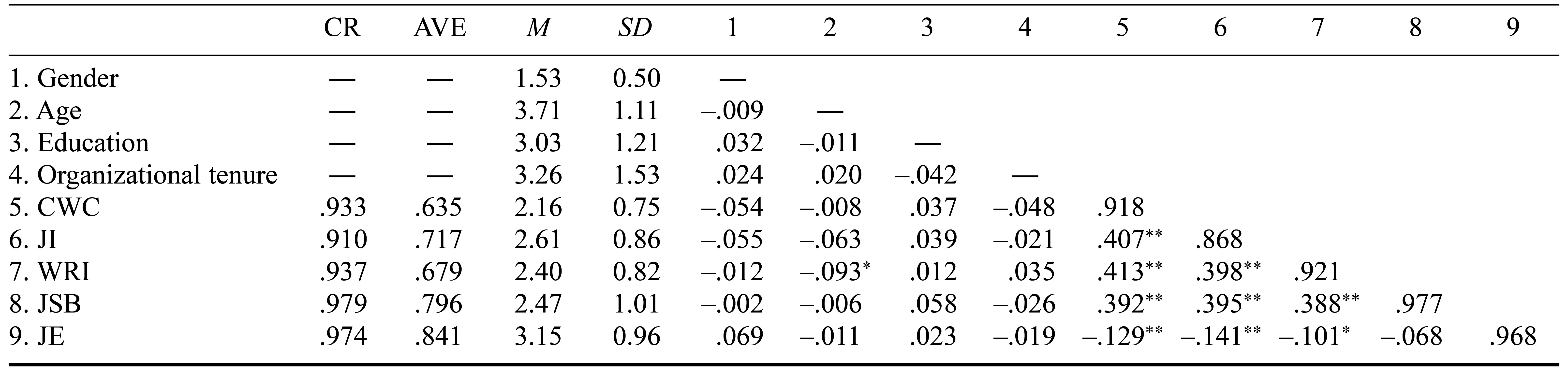

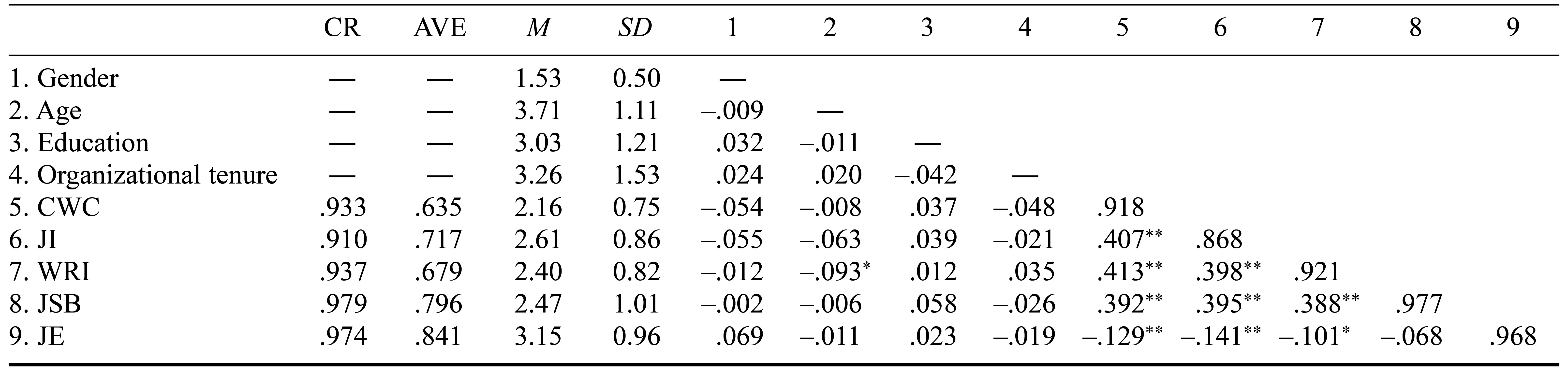

Descriptive Statistics

The mean values, standard deviations, and correlations among the measures are presented in Table 2. The correlations observed between key variables aligned closely with our expected results, providing preliminary support for the hypotheses.

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of Study Variables

Note. N = 571. CWC = COVID-19-related work changes; JI = job insecurity; WRI = work-related information seeking; JSB = job-seeking behavior; JE = job embeddedness. Cronbach’s alpha values are shown on the diagonal.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

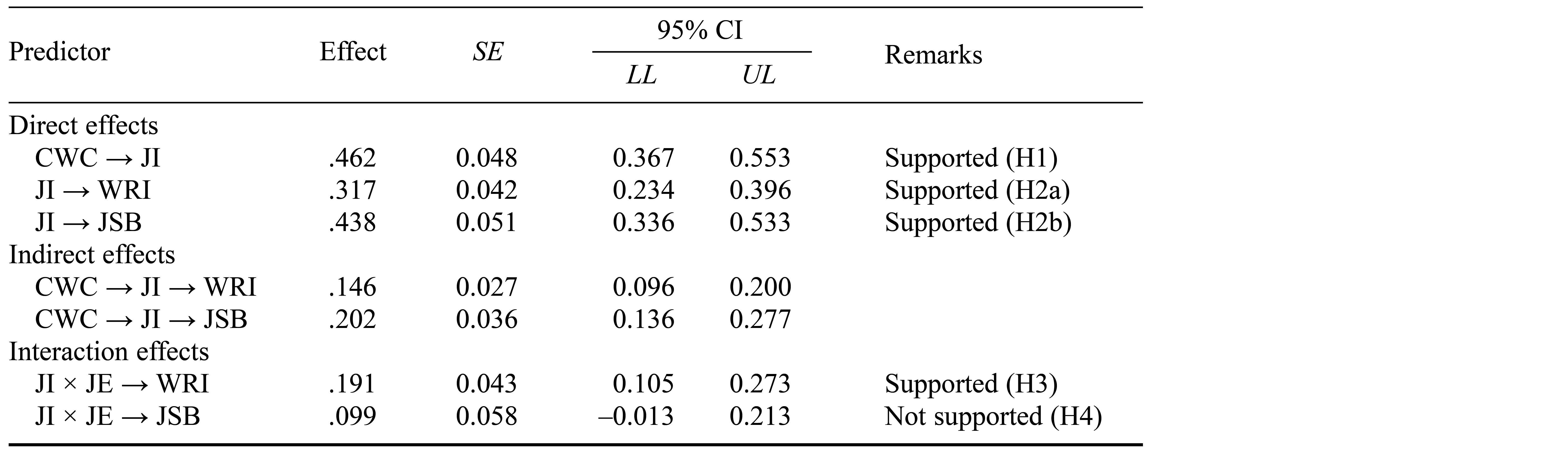

Hypothesis Testing

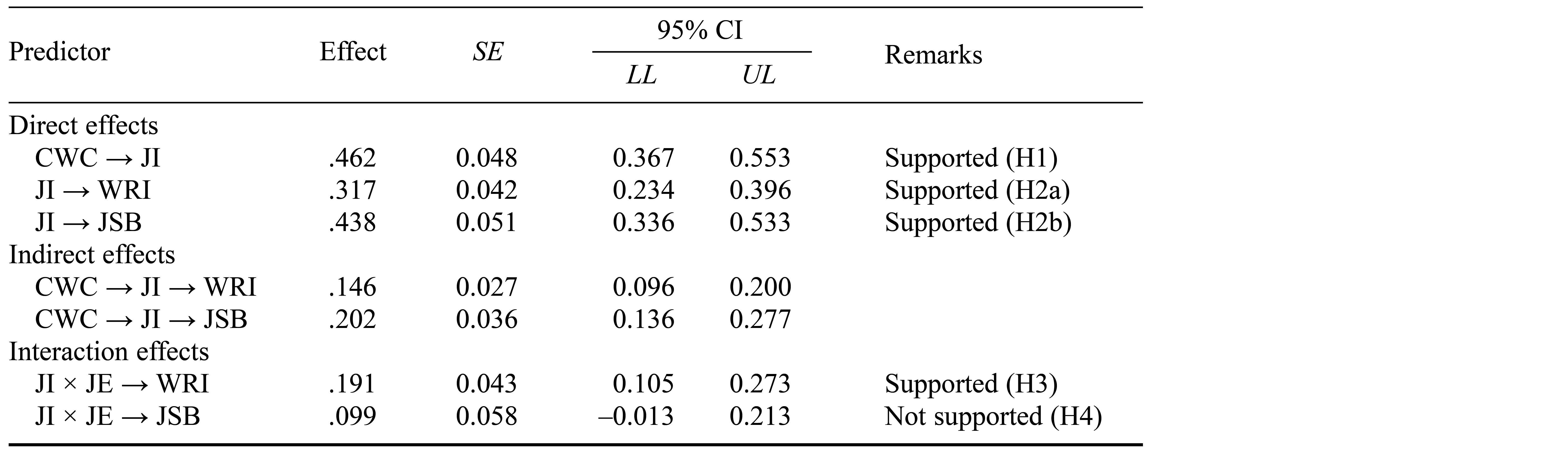

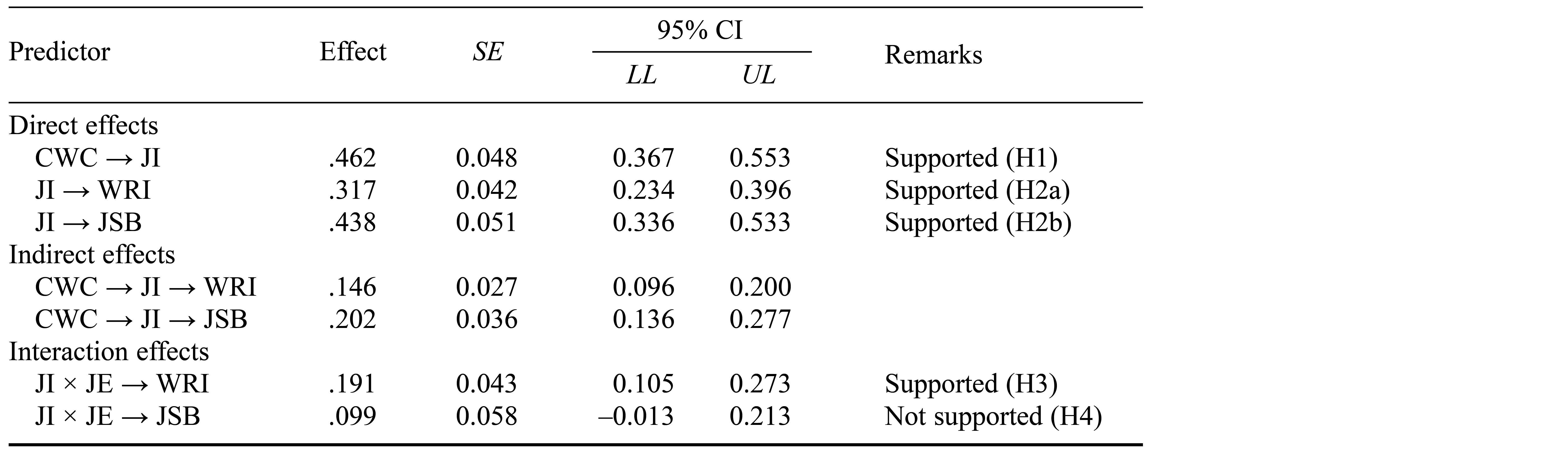

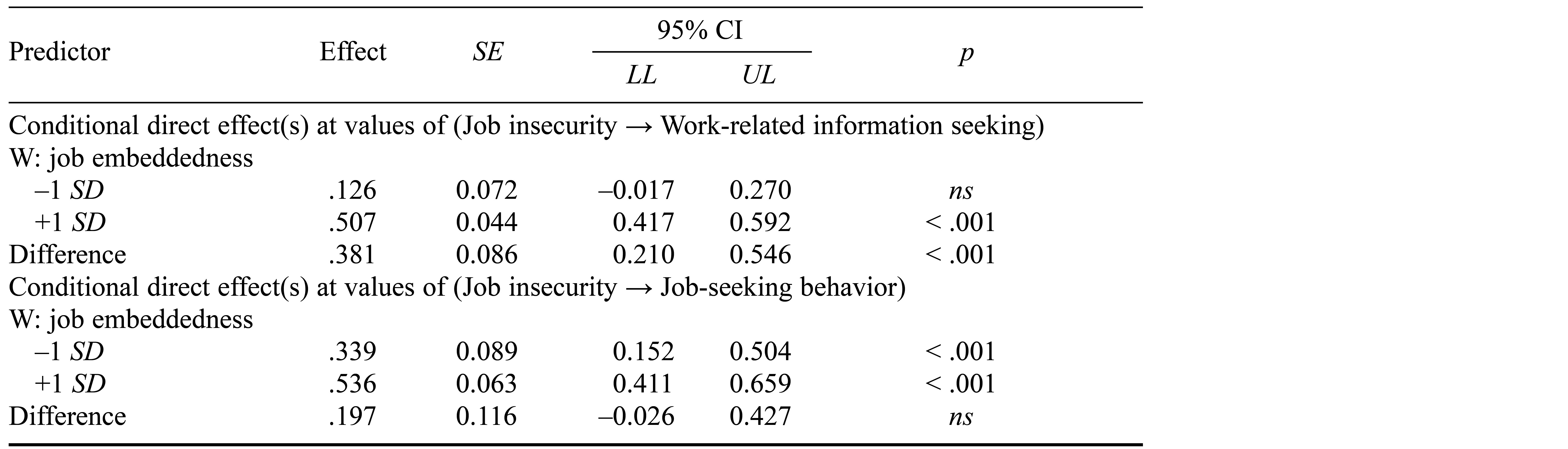

To test the hypotheses we constructed a structural equation model using Mplus 8.3, employing maximum likelihood estimation and 5,000 bootstrapped resamples (see Table 3). There was a positive relationship between job insecurity and COVID-19-related work changes, supporting Hypothesis 1. Job insecurity showed a positive relationship with both work-related information-seeking and job-seeking behavior. Thus, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported.

Table 3. Summary of Direct Effects

Note. N = 571. CWC = COVID-19-related work changes; JI = job insecurity; WRI = work-related information seeking; JSB = job-seeking behavior; JE = job embeddedness; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

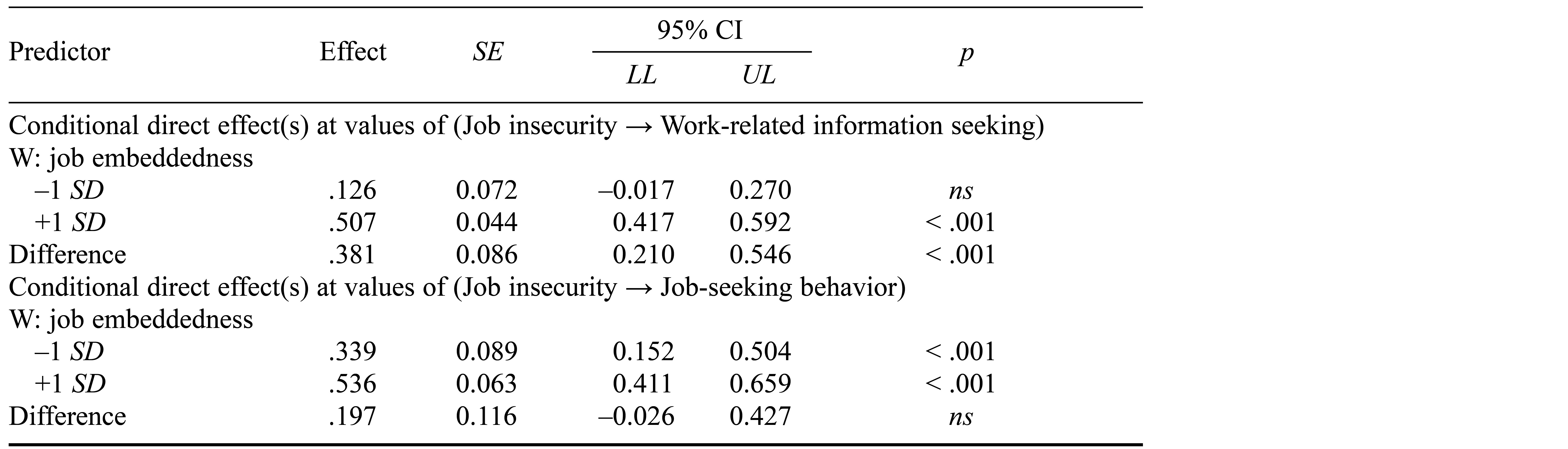

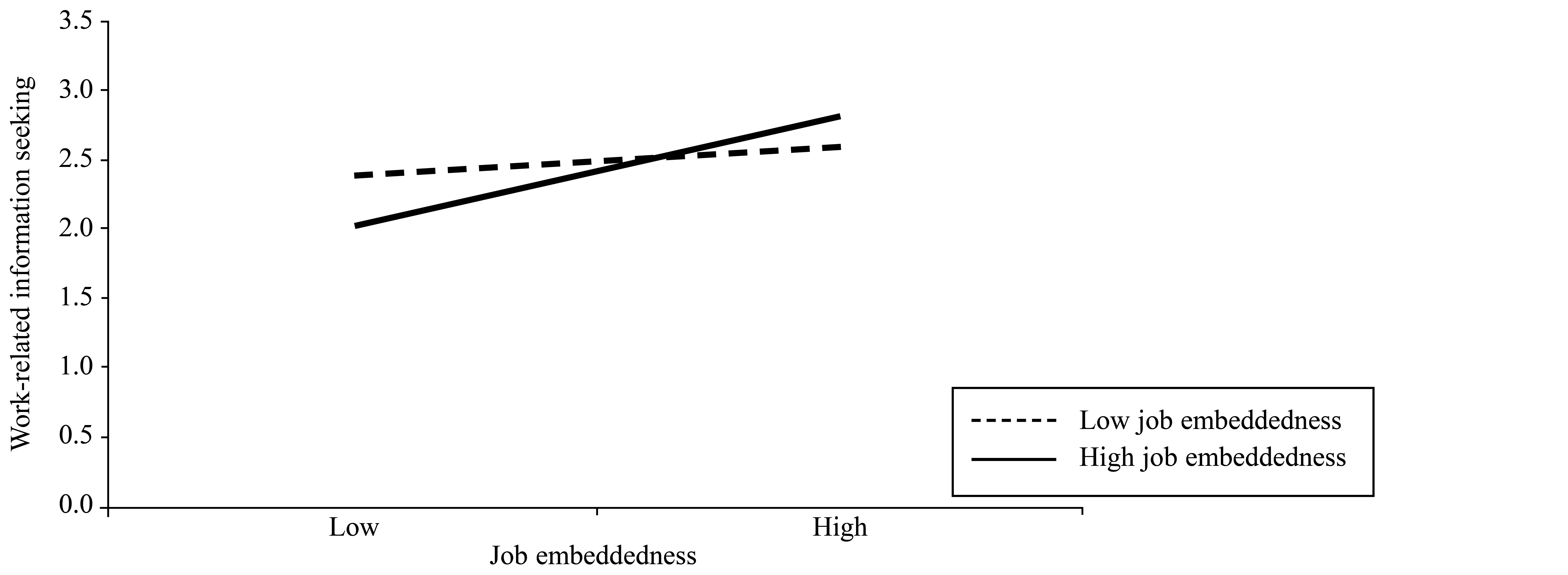

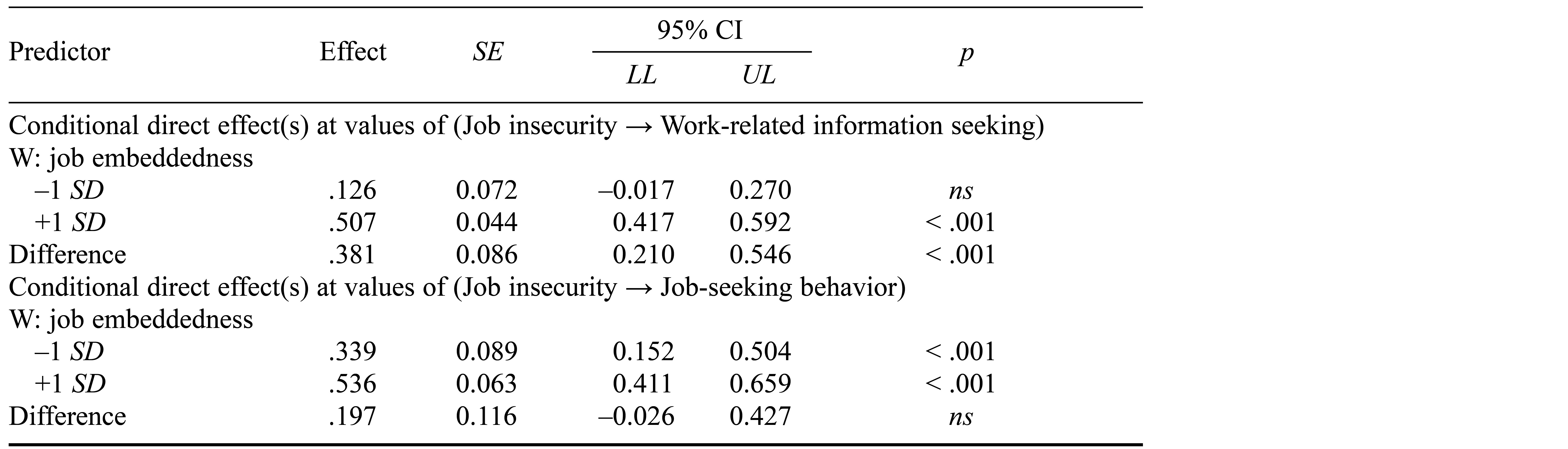

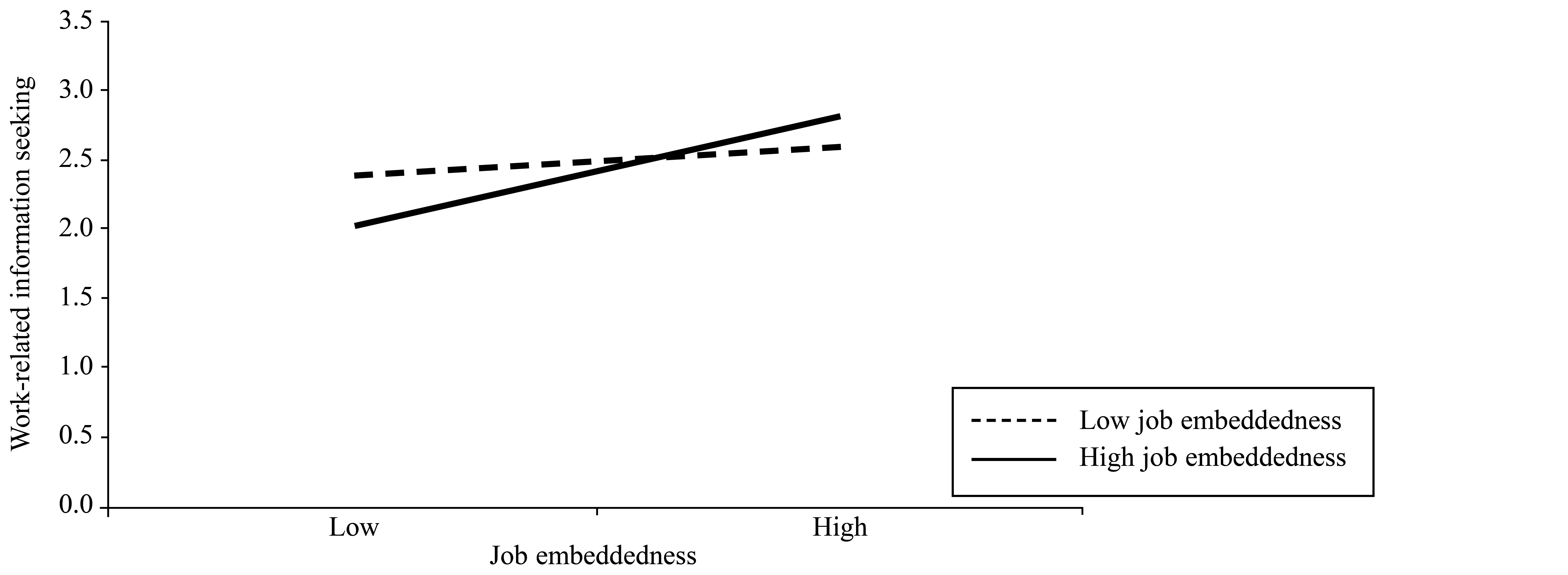

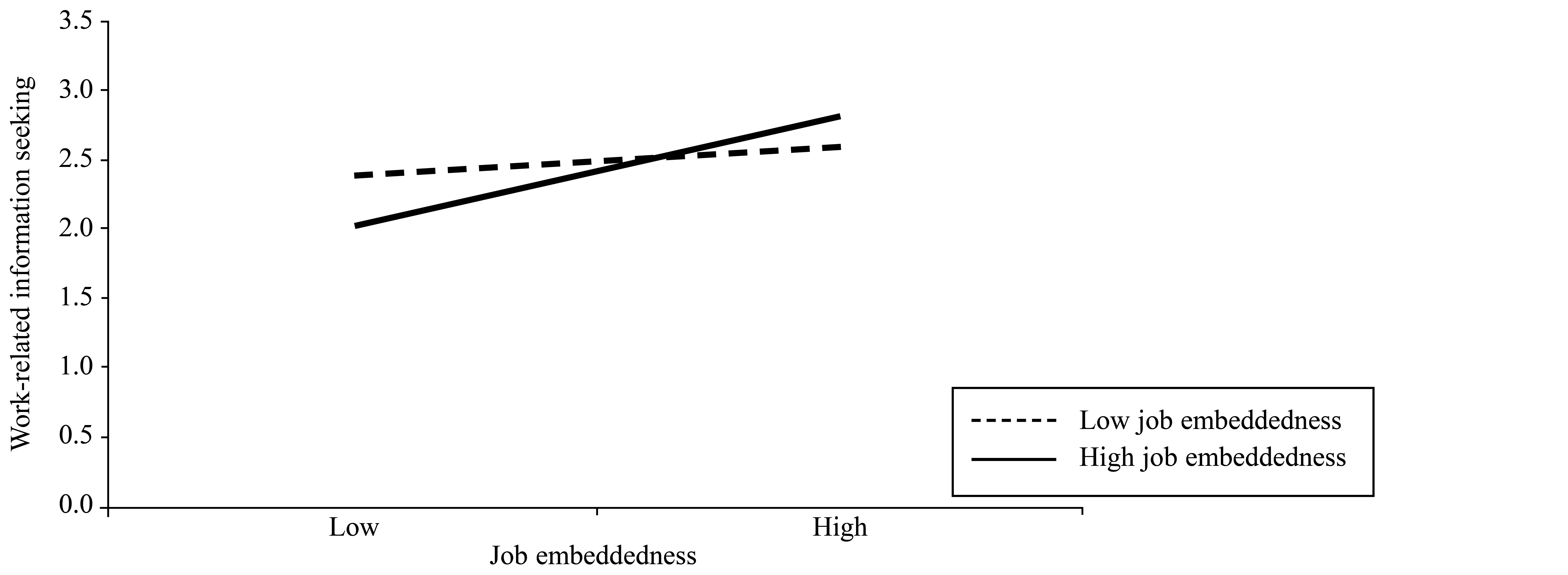

As can be seen in Table 4 and Figure 2, the interaction between job insecurity and job embeddedness positively predicted work-related information seeking. The interaction between job insecurity and job embeddedness was not significantly associated with job-seeking behavior, supporting Hypothesis 3 but not supporting Hypothesis 4. The direct effect of job insecurity on work-related information seeking was significant at high but not low levels of job embeddedness.

Table 4. Summary of Moderating Effects

Note. N = 571. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

Figure 2. The Moderating Effect of Job Embeddedness on the Relationship Between Job Insecurity and Work-Related Information Seeking

Discussion

We developed a model to elucidate the mechanisms through which COVID-19-related job changes impact employees’ proactive behaviors at work. Specifically, we focused on two variables: employees’ work-related information seeking and job-seeking behaviors. Using affective events theory, we introduced job insecurity as a mediator and examined the moderating effect of job embeddedness on the impact of job insecurity on work-related information seeking and job-seeking behaviors. Our experimental results indicate that COVID-19-related job changes promoted job insecurity in employees, which, in turn, encouraged them to engage in work-related information seeking and job-seeking behaviors.

Additionally, we found that job embeddedness positively moderated the effect of job insecurity on information seeking. This implies that when job embeddedness is high, the positive relationship between job insecurity and work-related information seeking is stronger. However, our research results also indicate that job embeddedness did not act as a moderator of the relationship between job insecurity and job-seeking behavior. We believe that this result can be attributed to the context of COVID-19. Against the backdrop of large-scale layoffs because of the pandemic, employees tended to engage in job-seeking behaviors resulting from immense uncertainty (McFarland et al., 2020). In such a scenario, the effect of job insecurity might be so pronounced that it could negate the usual moderating role of job embeddedness. Furthermore, during prolonged events like COVID-19, the relationship between job insecurity and job-seeking behavior might change over time. Our data were collected at a single time point, which might also have contributed to the nonsignificant moderating effect we observed.

Theoretical Implications

Our research offers numerous valuable contributions. First, we have extended the literature on the impact of COVID-19-related work changes on job insecurity and subsequent employee behaviors. By reviewing the existing literature, we found that the focus in previous studies was on the negative consequences of work changes caused by COVID-19, such as burnout leading to negative employee behaviors, including decline in mental health, interpersonal conflicts, and aggressiveness (X. Liu et al., 2023), and how job insecurity can lead to negative employee behaviors such as reduced work engagement, participation, and professional attitudes (C. Lee et al., 2018), while neglecting the positive behaviors employees may exhibit in this process. Consequently, our theoretical framework extends understanding of the impact of work changes on employees to previously unexplored domains, highlighting a proactive aspect of employee behaviors in the face of adversity.

Second, we revealed the potential mechanisms of how COVID-19-related job changes affect information seeking and job-seeking behaviors, by emphasizing the mediating role of job insecurity. Previous researchers have concentrated on the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic itself on these behaviors (McFarland et al., 2020; Pan & Zhang, 2020). However, relatively few scholars have studied its operating mechanisms. In this research we constructed a framework showing how COVID-19-related job changes influence employee information search and job-seeking behaviors through job insecurity, thereby initiating exploration of how pandemic-related job changes have affected employees’ proactive behaviors in seeking their own career development.

Third, by recognizing job embeddedness as an important boundary condition, our study explains the moderating role of job insecurity in the employee information-search process. Previous researchers mostly focused on job embeddedness as a mediator directly influencing employee work behavior (see, e.g., Holtom et al., 2012), overlooking its moderating role. Our research finding suggests that employees’ job embeddedness amplifies the process by which job insecurity affects their work behavior, highlighting the role of job embeddedness in the context of COVID-19 and expanding the literature in this field.

Practical Implications

Our research findings suggest three key strategies for organizations in the context of a crisis environment, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. First, addressing the job insecurity stemming from pandemic-induced work changes is essential. This could be done through transparent communication about job stability and introducing flexible work arrangements to alleviate employee concerns. Second, in a crisis environment, managers of organizations should focus on the psychological well-being of their employees to reduce turnover, making them feel valued and secure through opportunities for professional growth. Last, enhancing job embeddedness is important because it can positively moderate the impact of job insecurity on employees’ information-seeking behavior. Investing in employee benefits, such as health insurance and retirement plans, can increase job commitment and foster a culture of growth and loyalty within the organization.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study contains several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design we employed hinders the establishment of causality, suggesting a need for future longitudinal studies to better understand the dynamics between COVID-19-related work changes and the outcomes. Second, the focus on China may limit the findings’ applicability to other contexts, particularly in developed nations with different sociocultural backgrounds. Therefore, further research in varied international settings is recommended. Third, the absence of a significant moderating effect by job embeddedness on the relationship between job insecurity and employee job-seeking behavior indicates a potential area for future research to explore alternative moderating factors.

References

Ambrogio, G., Filice, L., Longo, F., & Padovano, A. (2022). Workforce and supply chain disruption as a digital and technological innovation opportunity for resilient manufacturing systems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 169, Article 108158.

Ashford, S. J., Lee, C., & Bobko, P. (1989). Content, cause, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal, 32(4), 803–829.

Astarlioglu, M., Kazozcu, S. B., & Varnalia, R. (2011). A qualitative study of coping strategies in the context of job insecurity. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 421–434.

Bauer, F., Friesl, M., & Dao, M. A. (2022). Run or hide: Changes in acquisition behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Strategy and Management, 15(1), 38–53.

Blackmore, C., & Kuntz, J. R. C. (2011). Antecedents of job insecurity in restructuring organisations: An empirical investigation. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 7–18.

Blau, G. (1994). Testing a two-dimensional measure of job search behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 59(2), 288–312.

Blustein, D. L., Duffy, R., Ferreira, J. A., Cohen-Scali, V., Cinamon, R. G., & Allan, B. A. (2020). Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: A research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, Article 103436.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon.

Brown, S. P., Ganesan, S., & Challagalla, G. (2001). Self-efficacy as a moderator of information-seeking effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 1043–1051.

Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., & Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031–1042.

Dahmani, A., & Gasmi, Z. (2022). Downsizing in times of COVID-19: The difficult reconciliation between the social and the economic. The case of the survivors of a hotel establishment in Tunisia [In French]. Relations Industrielles-Industrial Relations, 77(2), 1–17.

De Cuyper, N., De Witte, H., Vander Elst, T., & Handaja, Y. (2010). Objective threat of unemployment and situational uncertainty during a restructuring: Associations with perceived job insecurity and strain. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 75–85.

Grunberg, L., Moore, S., & Greenberg, E. S. (2006). Managers’ reactions to implementing layoffs: Relationship to health problems and withdrawal behaviors. Human Resource Management, 45(2), 159–178.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work & Stress, 22(3), 242–256.

Han, C., Zhang, R., Liu, X., Wang, X., & Liu, X. (2023). The virus made me lose control: The impact of COVID-related work changes on employees’ mental health, aggression, and interpersonal conflict. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, Article 1119389.

Holtom, B. C., Burton, J. P., & Crossley, C. D. (2012). How negative affectivity moderates the relationship between shocks, embeddedness and worker behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 434–443.

Hom, P. W., Tsui, A. S., Wu, J. B., Lee, T. W., Zhang, A. Y., Fu, P. P., & Li, L. (2009). Explaining employment relationships with social exchange and job embeddedness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 277–297.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), 819–834.

Lee, C., Huang, G.-H., & Ashford, S. J. (2018). Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 335–359.

Lee, T. W., Burch, T. C., & Mitchell, T. R. (2014). The story of why we stay: A review of job embeddedness. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 199–216.

Lian, H., Li, J. K., Du, C., Wu, W., Xia, Y., & Lee, C. (2022). Disaster or opportunity? How COVID-19-associated changes in environmental uncertainty and job insecurity relate to organizational identification and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(5), 693–706.

Liu, W., Xu, Y., & Ma, D. (2021). Work-related mental health under COVID-19 restrictions: A mini literature review. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, Article 788370.

Liu, X., Han, C., Xia, Y., & Liu, X. (2023). Different concerns, different choices: How does COVID-19-induced work uncertainty influence employees’ impression management? Current Psychology. Advance online publication.

Loretto, W., Platt, S., & Popham, F. (2010). Workplace change and employee mental health: Results from a longitudinal study. British Journal of Management, 21(2), 526–540.

Madero Gómez, S., Ortiz Mendoza, O. E., Ramírez, J., & Olivas-Luján, M. R. (2020). Stress and myths related to the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on remote work. Management Research, 18(4), 401–420.

McFarland, L. A., Reeves, S., Porr, W. B., & Ployhart, R. E. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on job search behavior: An event transition perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1207–1217.

Mihalache, M., & Mihalache, O. R. (2022). How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees’ affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Human Resource Management, 61(3), 295–314.

Miller, V. D., & Jablin, F. M. (1991). Information seeking during organizational entry: Influences, tactics, and a model of the process. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 92–120.

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121.

Mitchell, T. R., & Lee, T. W. (2001). The unfolding model of voluntary turnover and job embeddedness: Foundations for a comprehensive theory of attachment. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 189–246.

Pan, S. L., & Zhang, S. (2020). From fighting COVID-19 pandemic to tackling sustainable development goals: An opportunity for responsible information systems research. International Journal of Information Management, 55, Article 102196.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224–253.

Schmit, M. J., Amel, E. L., & Ryan, A. M. (1993). Self‐reported assertive job‐seeking behaviors of minimally educated job hunters. Personnel Psychology, 46(1), 105–124.

Schreurs, B. H., van Emmerik, H., Günter, H., & Germeys, F. (2012). A weekly diary study on the buffering role of social support in the relationship between job insecurity and employee performance. Human Resource Management, 51(2), 259–279.

Sombultawee, K., Lenuwat, P., Aleenajitpong, N., & Boon-itt, S. (2022). COVID-19 and supply chain management: A review with bibliometric. Sustainability, 14(6), Article 3538.

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(3), 242–264.

Venkatesh, V. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19: A research agenda to support people in their fight. International Journal of Information Management, 55, Article 102197.

Wanberg, C. R., Watt, J. D., & Rumsey, D. J. (1996). Individuals without jobs: An empirical study of job-seeking behavior and reemployment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(1), 76–87.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Wheeler, A. R., Harris, K. J., & Sablynski, C. J. (2012). How do employees invest abundant resources? The mediating role of work effort in the job‐embeddedness/job‐performance relationship. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(S1), E244–E266.

Wolfe Morrison, E. (1993). Newcomer information seeking: Exploring types, modes, sources, and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 557–589.

Yao, X., Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Burton, J. P., & Sablynski, C. S. (2004). Job embeddedness: Current research and future directions. In R. Griffeth & P. Hom (Eds.), Innovative theory and empirical research on employee turnover (pp. 153–187). Information Age.

Ambrogio, G., Filice, L., Longo, F., & Padovano, A. (2022). Workforce and supply chain disruption as a digital and technological innovation opportunity for resilient manufacturing systems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 169, Article 108158.

Ashford, S. J., Lee, C., & Bobko, P. (1989). Content, cause, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal, 32(4), 803–829.

Astarlioglu, M., Kazozcu, S. B., & Varnalia, R. (2011). A qualitative study of coping strategies in the context of job insecurity. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 421–434.

Bauer, F., Friesl, M., & Dao, M. A. (2022). Run or hide: Changes in acquisition behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Strategy and Management, 15(1), 38–53.

Blackmore, C., & Kuntz, J. R. C. (2011). Antecedents of job insecurity in restructuring organisations: An empirical investigation. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 7–18.

Blau, G. (1994). Testing a two-dimensional measure of job search behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 59(2), 288–312.

Blustein, D. L., Duffy, R., Ferreira, J. A., Cohen-Scali, V., Cinamon, R. G., & Allan, B. A. (2020). Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: A research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, Article 103436.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon.

Brown, S. P., Ganesan, S., & Challagalla, G. (2001). Self-efficacy as a moderator of information-seeking effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 1043–1051.

Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., & Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031–1042.

Dahmani, A., & Gasmi, Z. (2022). Downsizing in times of COVID-19: The difficult reconciliation between the social and the economic. The case of the survivors of a hotel establishment in Tunisia [In French]. Relations Industrielles-Industrial Relations, 77(2), 1–17.

De Cuyper, N., De Witte, H., Vander Elst, T., & Handaja, Y. (2010). Objective threat of unemployment and situational uncertainty during a restructuring: Associations with perceived job insecurity and strain. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 75–85.

Grunberg, L., Moore, S., & Greenberg, E. S. (2006). Managers’ reactions to implementing layoffs: Relationship to health problems and withdrawal behaviors. Human Resource Management, 45(2), 159–178.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work & Stress, 22(3), 242–256.

Han, C., Zhang, R., Liu, X., Wang, X., & Liu, X. (2023). The virus made me lose control: The impact of COVID-related work changes on employees’ mental health, aggression, and interpersonal conflict. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, Article 1119389.

Holtom, B. C., Burton, J. P., & Crossley, C. D. (2012). How negative affectivity moderates the relationship between shocks, embeddedness and worker behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 434–443.

Hom, P. W., Tsui, A. S., Wu, J. B., Lee, T. W., Zhang, A. Y., Fu, P. P., & Li, L. (2009). Explaining employment relationships with social exchange and job embeddedness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 277–297.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), 819–834.

Lee, C., Huang, G.-H., & Ashford, S. J. (2018). Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 335–359.

Lee, T. W., Burch, T. C., & Mitchell, T. R. (2014). The story of why we stay: A review of job embeddedness. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 199–216.

Lian, H., Li, J. K., Du, C., Wu, W., Xia, Y., & Lee, C. (2022). Disaster or opportunity? How COVID-19-associated changes in environmental uncertainty and job insecurity relate to organizational identification and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(5), 693–706.

Liu, W., Xu, Y., & Ma, D. (2021). Work-related mental health under COVID-19 restrictions: A mini literature review. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, Article 788370.

Liu, X., Han, C., Xia, Y., & Liu, X. (2023). Different concerns, different choices: How does COVID-19-induced work uncertainty influence employees’ impression management? Current Psychology. Advance online publication.

Loretto, W., Platt, S., & Popham, F. (2010). Workplace change and employee mental health: Results from a longitudinal study. British Journal of Management, 21(2), 526–540.

Madero Gómez, S., Ortiz Mendoza, O. E., Ramírez, J., & Olivas-Luján, M. R. (2020). Stress and myths related to the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on remote work. Management Research, 18(4), 401–420.

McFarland, L. A., Reeves, S., Porr, W. B., & Ployhart, R. E. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on job search behavior: An event transition perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1207–1217.

Mihalache, M., & Mihalache, O. R. (2022). How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees’ affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Human Resource Management, 61(3), 295–314.

Miller, V. D., & Jablin, F. M. (1991). Information seeking during organizational entry: Influences, tactics, and a model of the process. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 92–120.

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121.

Mitchell, T. R., & Lee, T. W. (2001). The unfolding model of voluntary turnover and job embeddedness: Foundations for a comprehensive theory of attachment. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 189–246.

Pan, S. L., & Zhang, S. (2020). From fighting COVID-19 pandemic to tackling sustainable development goals: An opportunity for responsible information systems research. International Journal of Information Management, 55, Article 102196.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224–253.

Schmit, M. J., Amel, E. L., & Ryan, A. M. (1993). Self‐reported assertive job‐seeking behaviors of minimally educated job hunters. Personnel Psychology, 46(1), 105–124.

Schreurs, B. H., van Emmerik, H., Günter, H., & Germeys, F. (2012). A weekly diary study on the buffering role of social support in the relationship between job insecurity and employee performance. Human Resource Management, 51(2), 259–279.

Sombultawee, K., Lenuwat, P., Aleenajitpong, N., & Boon-itt, S. (2022). COVID-19 and supply chain management: A review with bibliometric. Sustainability, 14(6), Article 3538.

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(3), 242–264.

Venkatesh, V. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19: A research agenda to support people in their fight. International Journal of Information Management, 55, Article 102197.

Wanberg, C. R., Watt, J. D., & Rumsey, D. J. (1996). Individuals without jobs: An empirical study of job-seeking behavior and reemployment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(1), 76–87.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Wheeler, A. R., Harris, K. J., & Sablynski, C. J. (2012). How do employees invest abundant resources? The mediating role of work effort in the job‐embeddedness/job‐performance relationship. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(S1), E244–E266.

Wolfe Morrison, E. (1993). Newcomer information seeking: Exploring types, modes, sources, and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 557–589.

Yao, X., Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Burton, J. P., & Sablynski, C. S. (2004). Job embeddedness: Current research and future directions. In R. Griffeth & P. Hom (Eds.), Innovative theory and empirical research on employee turnover (pp. 153–187). Information Age.