Artificial intelligence service reduces customer citizenship behavior for warm brands versus competent brands

Main Article Content

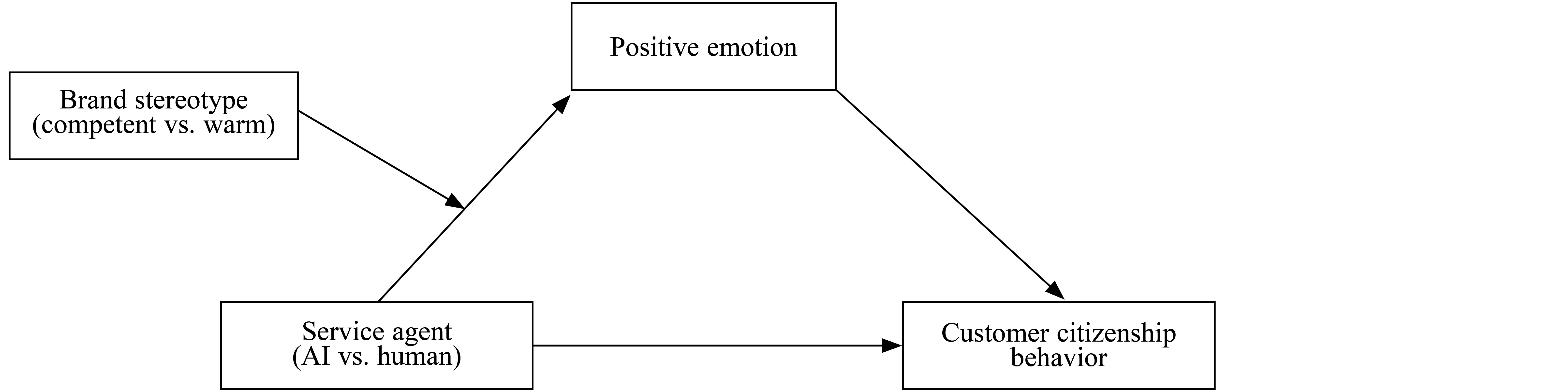

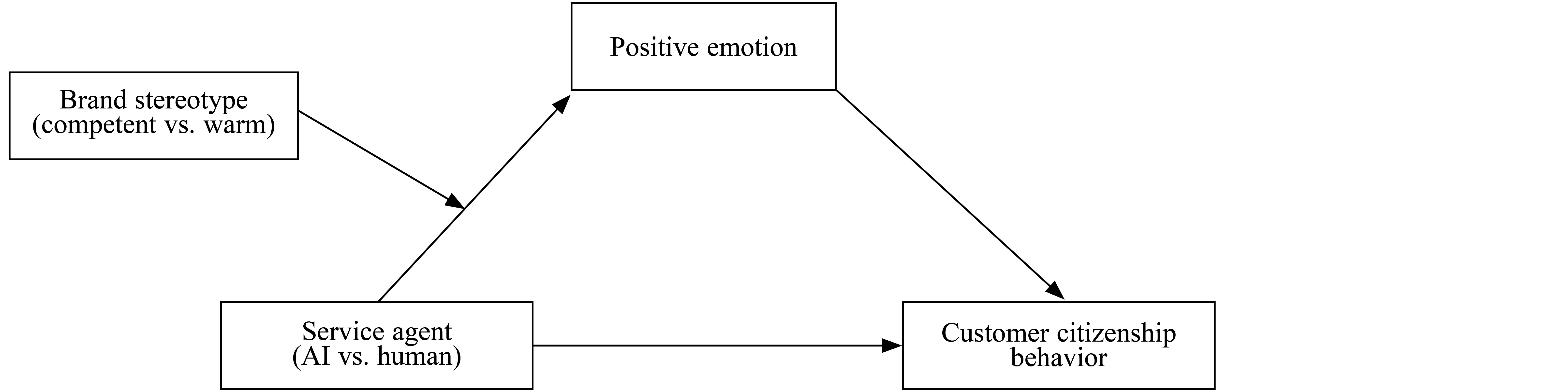

Chatbot services powered by artificial intelligence (AI) have begun to replace staff on the frontline in various industries. This research examined how AI service affects customer citizenship behavior. Drawing on emotional spillover theory, we conducted two experiments (Ns = 140 and 200). The results demonstrated there was a negative effect of AI (vs. human) service on customer citizenship behavior and identified positive emotion as the underlying mechanism of this effect (Study 1). Additionally, brand stereotypes were found to moderate the relationship between service type and positive emotions (Study 2). Specifically, the relationship became weaker for competent (vs. warm) brand service. These findings contribute to promoting customer citizenship behavior in unmanned contexts and provide insights for the application of AI services in frontline operations.

Artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots have been developed as digital agents to enhance customer experience through instant interactions (Song et al., 2022). They have begun to replace traditional staff in various industries, such as online retailing, tourism, and hospitality (Song et al., 2022). For example, Marriott has employed Aloft’s ChatBotlr for customer consulting service during hotel stays. The global chatbot industry is expected to reach USD 3.99 billion by 2030, expanding at a compound annual growth rate of 25.7% from 2022 to 2030 (Grand View Research, Inc., 2022). While most previous research in this area has focused on enhancing customer acceptance of chatbots (Song et al., 2022), as their use grows there is an urgent need to consider the carry-over effect on customer response, including customer citizenship behavior. Customer citizenship behavior refers to extrarole behaviors (e.g., offering suggestions) that provide additional value to businesses (Gong & Yi, 2021), which is crucial for sustainable company development (Vargo & Lusch, 2017).

Existing research has focused primarily on customers’ cognitive attitude toward and response to chatbots, such as perceived effectiveness and satisfaction (Zhu et al., 2022). Few studies have paid attention to the impact of chatbots on customer emotions and their citizenship behaviors following use of the service. To address this gap, we proposed a framework (see Figure 1) based on emotional spillover theory, which posits that emotions generated in one role may engender spillover effects in another role (X. Zhou et al., 2022). Accordingly, we proposed that AI (vs. human) service would influence consumers’ positive emotion, leading to spillover effects on their customer citizenship behavior. As a result, our study contributes to the extant literature in several ways. First, while most existing research has examined the influence of macro-organizational factors on customer citizenship behavior, such as corporate social responsibility (Abdelmoety et al., 2022), limited attention has been given to the influence of micro-organizational factors. Therefore, we explored this aspect, starting from the service agent, to deepen understanding of customer citizenship behavior. Second, customer responses to AI agents are often emotional (Huang & Rust, 2021), yet most studies have focused on customers’ cognitive evaluation (Zhu et al., 2022). Our research broadens the perception of AI services to include emotional evaluation. Last, we argued that the desirability of AI service would be context-dependent (Ruan & Mezei, 2022). Thus, we sought to advance theoretical understanding by delineating the effect boundaries and providing management implications for service providers.

Study 1

Method

Participants

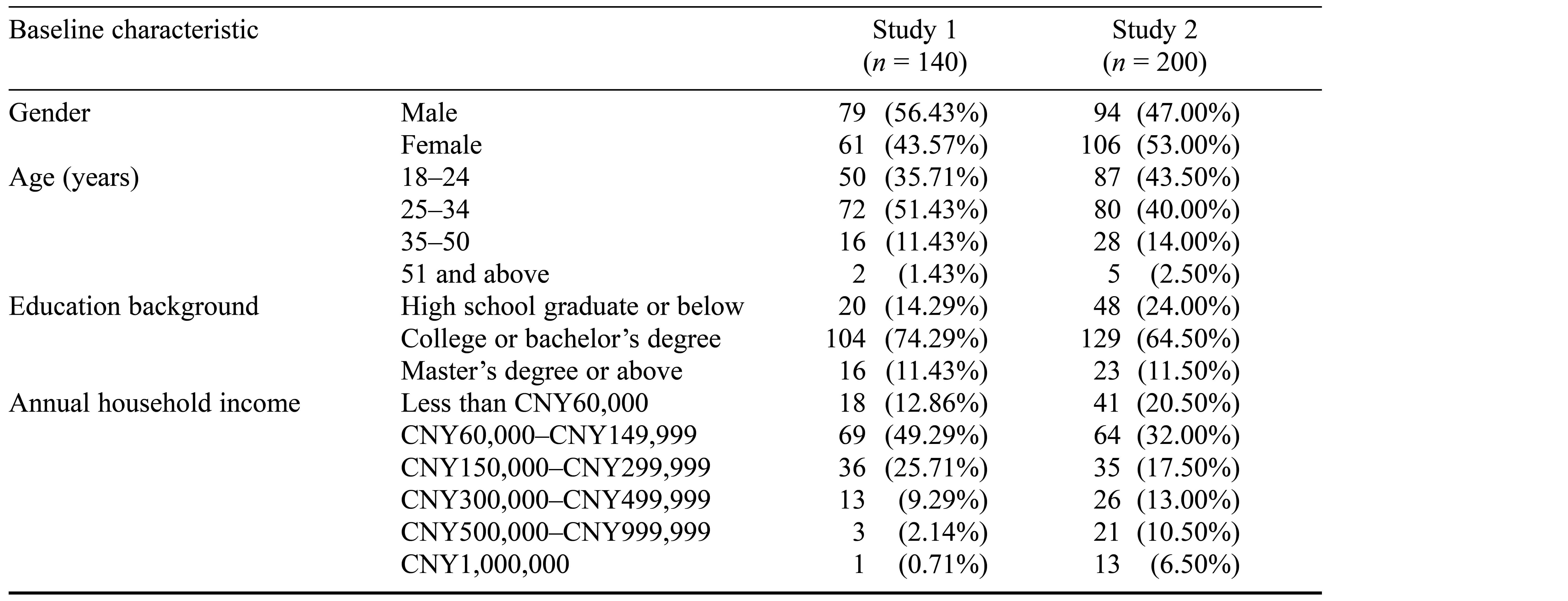

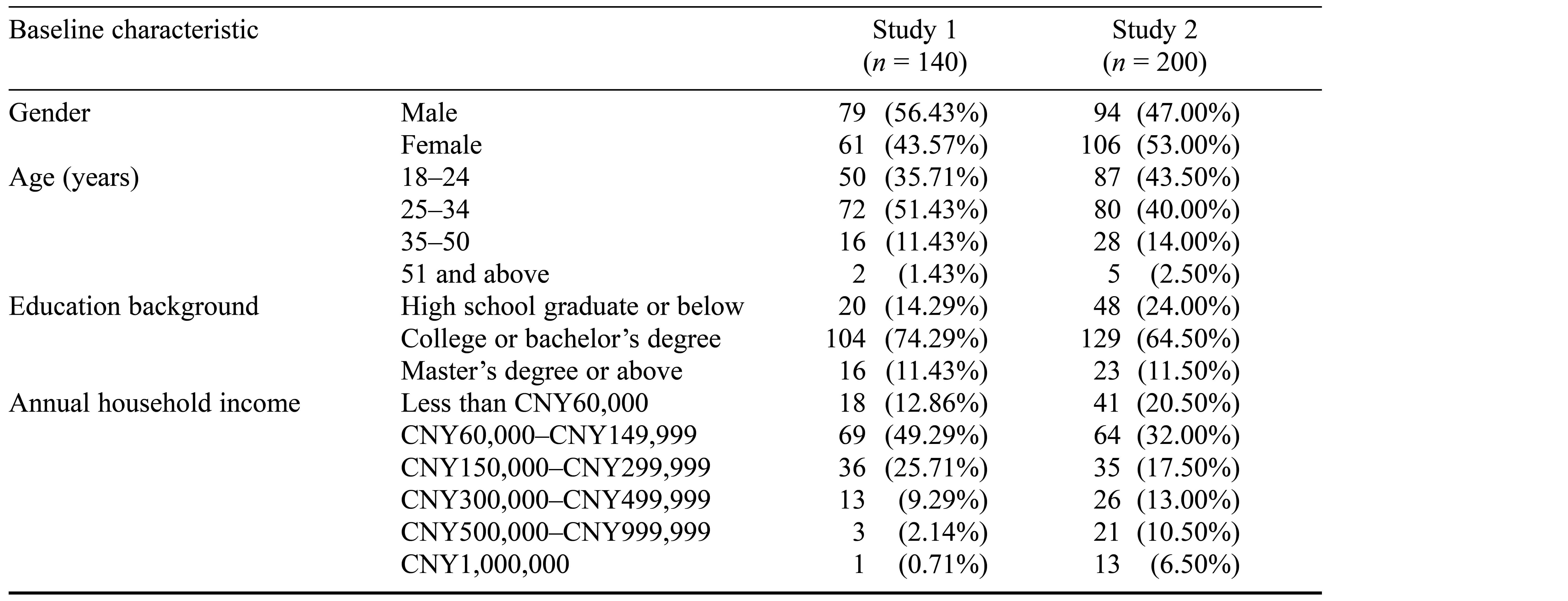

Table 1. Participants’ Demographic Profile

Note. Numbers in parentheses are the percentage of the total sample. CNY 1.00 = USD 0.14.

Procedure

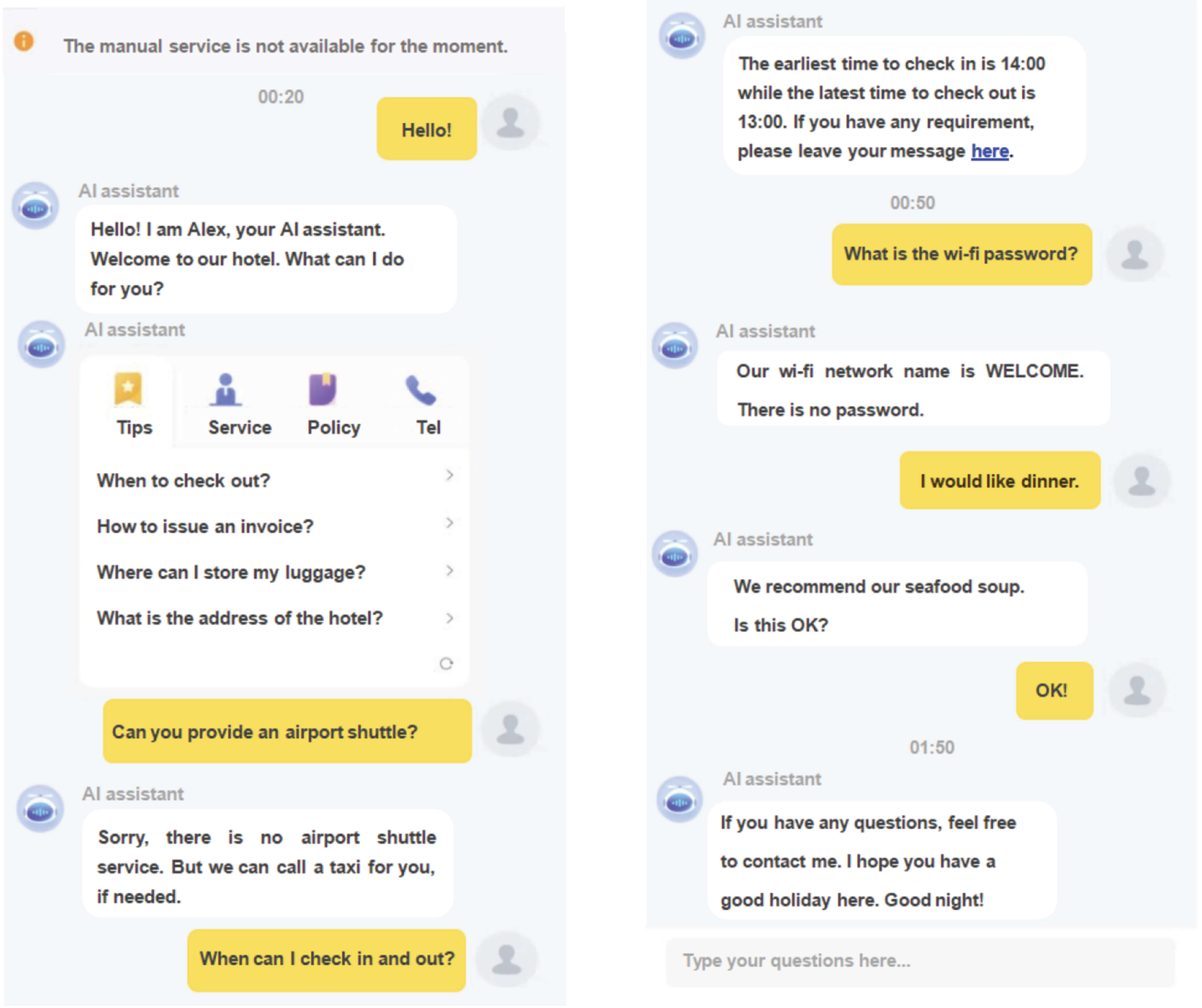

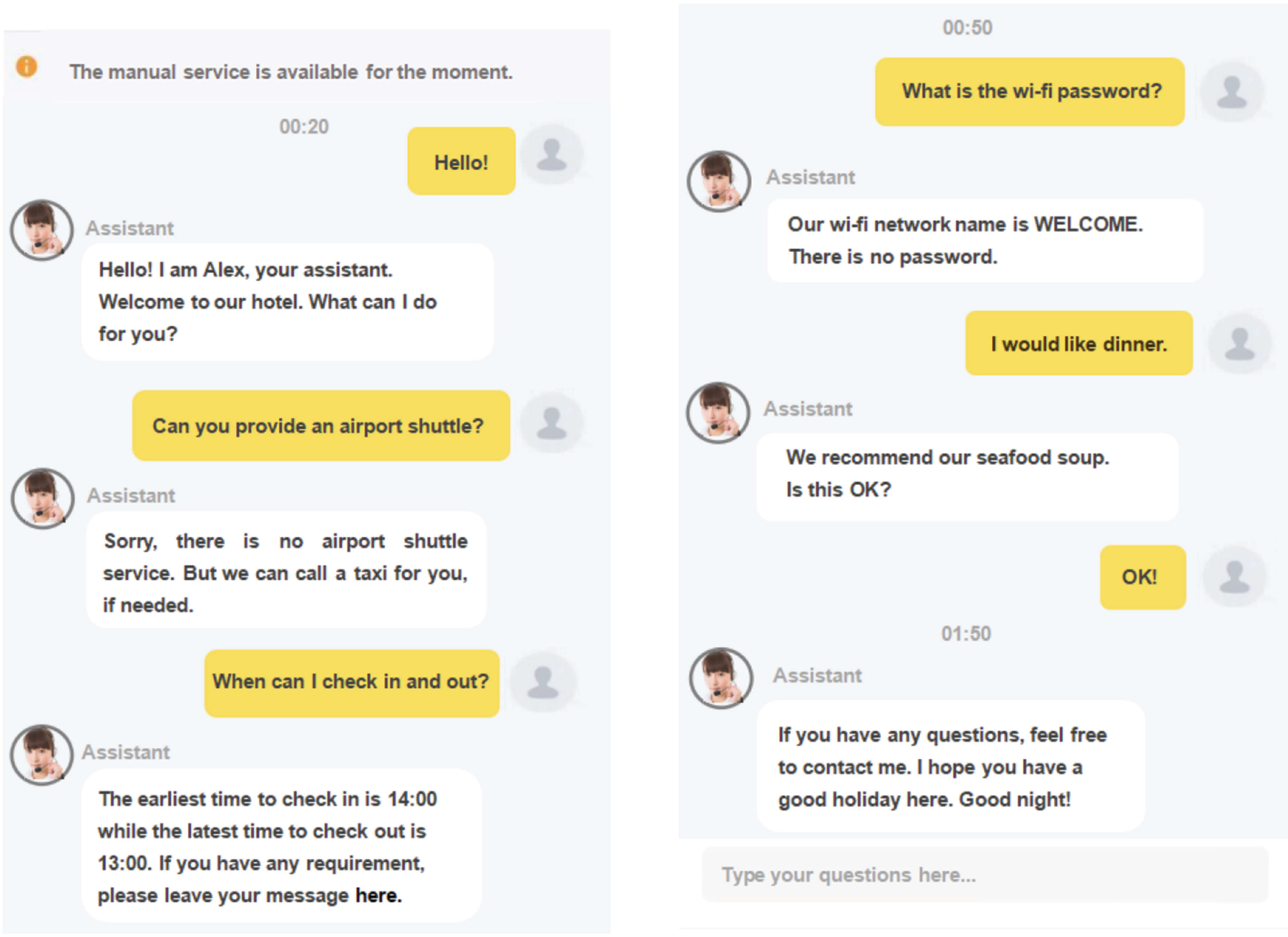

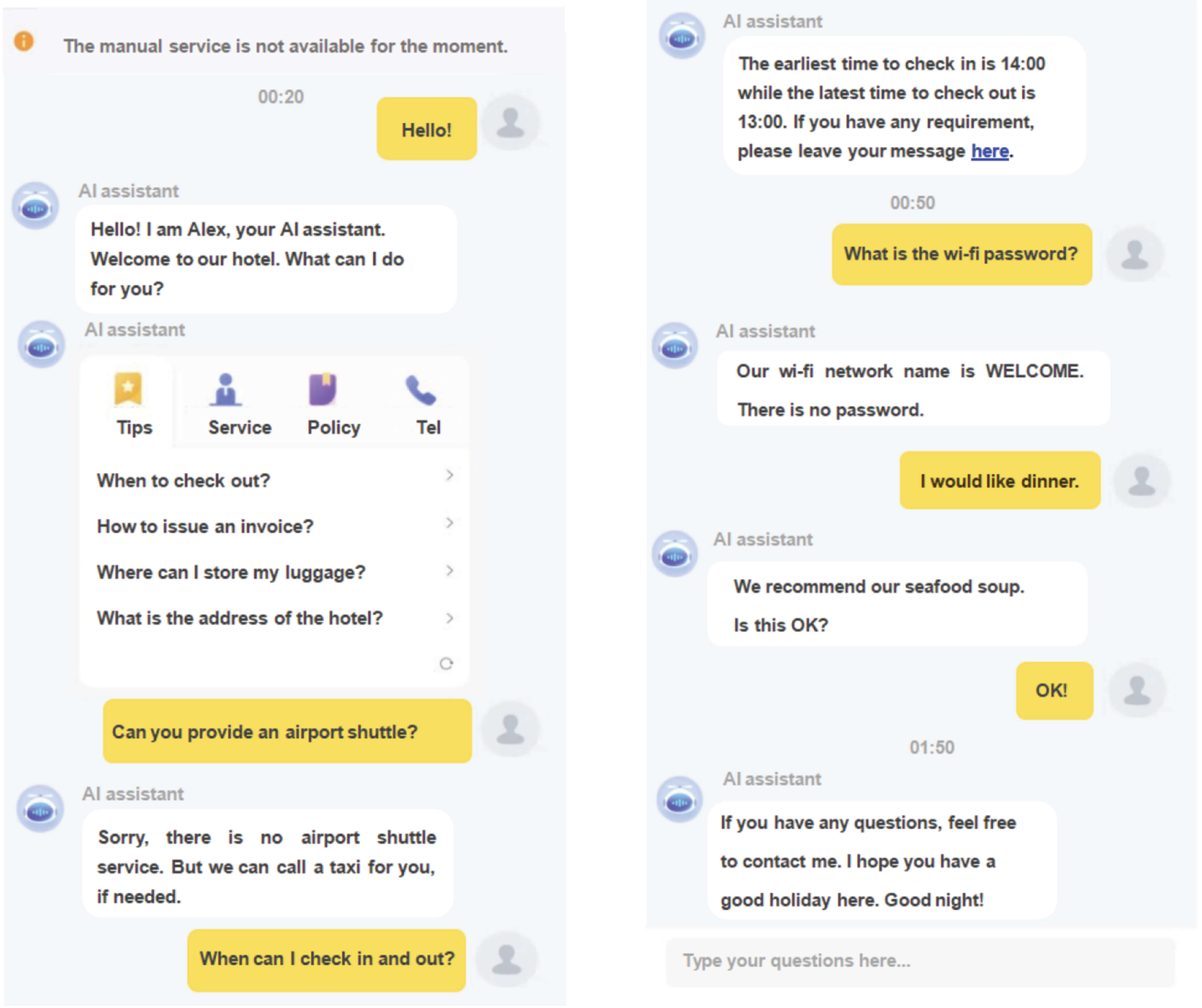

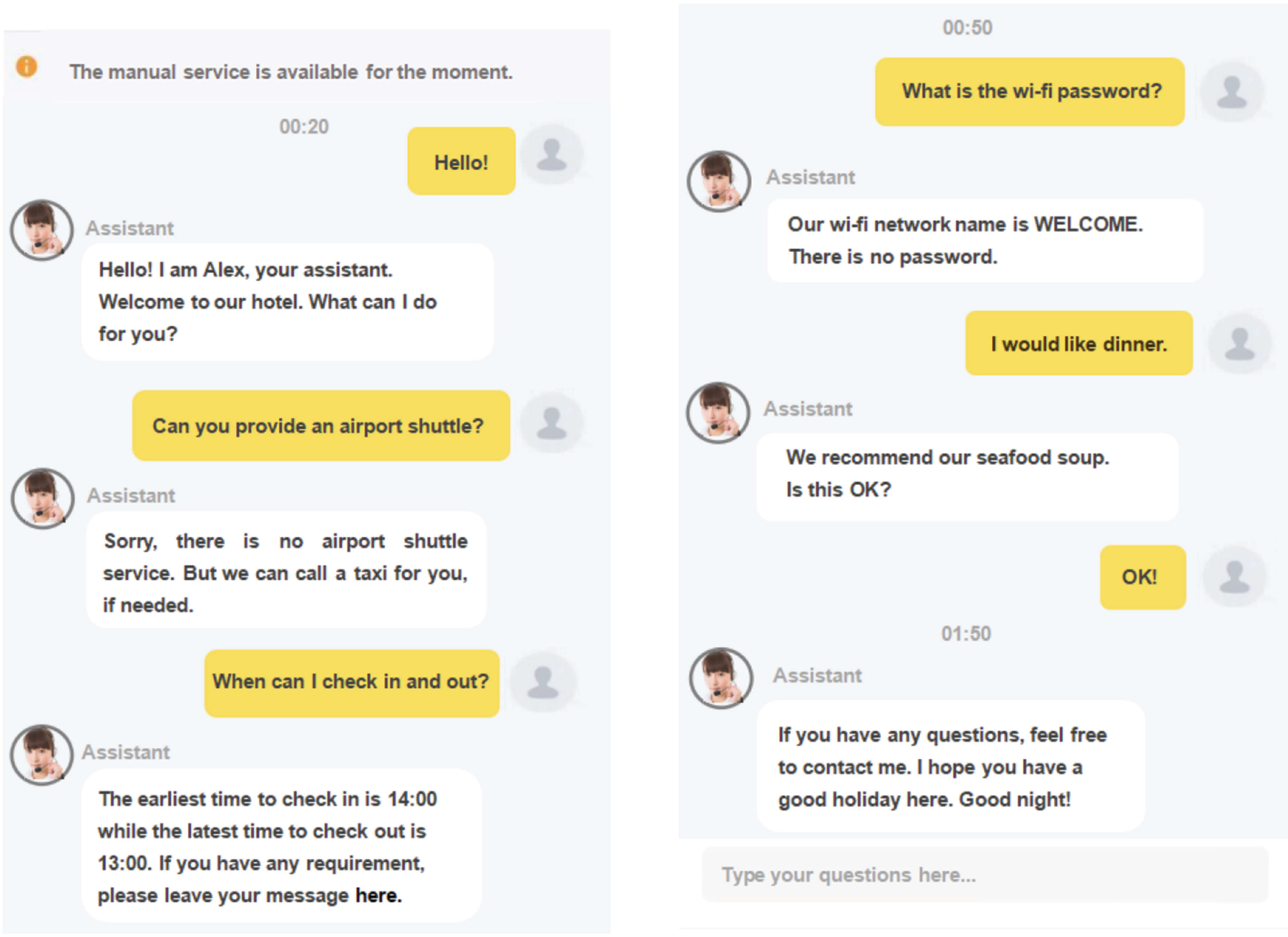

Participants were initially measured for positive emotion (α = .89; see Appendix A) before the test and were instructed to imagine themselves on vacation, having just arrived at the destination on their own. Then, participants in the two different service modes were instructed to act as the protagonist in the respective scenarios. AI service was indicated by a robot head portrait and preset replies (see Figure 2), while human service was indicated by a human head portrait (see Figure 3).

Afterward, participants reported their customer citizenship behavior, for which we used a five-item scale adapted from Yi and Gong (2013). A sample item is “If I have a useful idea on how to improve service, I let an employee know.” Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 = very unlikely and 7 = very likely. In our study Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

Positive emotion was measured with a four-item scale adapted from Sherman et al. (1997). A sample item is “To what extent are you feeling the following emotions: happy/satisfied/pleased/hopeful?” Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 = not at all and 7 = an extreme amount. In our study Cronbach’s alpha was .92.

Subsequently, a manipulation check for the service agent type was conducted using a two-item scale, r = .94. One of the items is “What is the possibility you thought the service was provided by AI?” Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 = very unlikely and 7 = very likely.

Finally, participants provided their demographic information. All participants signed a written consent form before the experiment and received compensation (USD 0.50) for their participation (as for Study 2). We obtained ethical approval for the research from an appropriate committee in our institution.

Figure 2. Artificial Intelligence Service Scenario

Figure 3. Human Service Scenario

Results

The results of an independent-samples t test showed that participants perceived higher humanless interaction in the AI service setting, M = 6.10, SD = 0.66, than in the human service setting, M = 3.42, SD = 0.53, t = 26.43, p < .01, d = 4.48. Thus, the manipulation was effective.

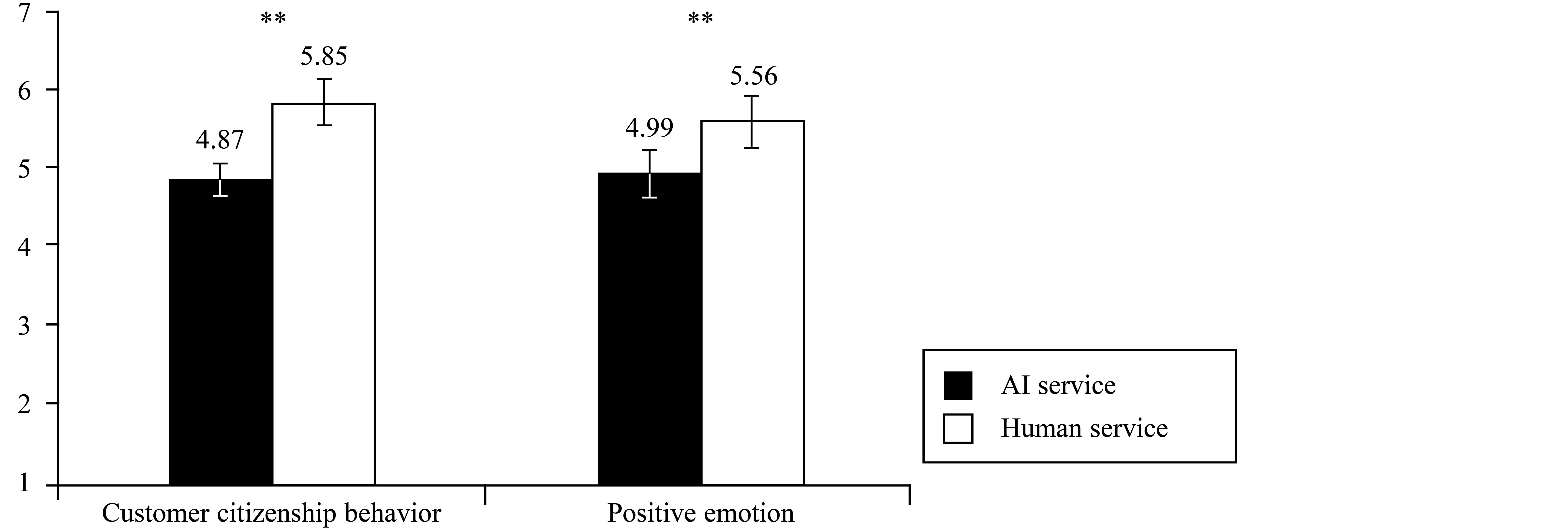

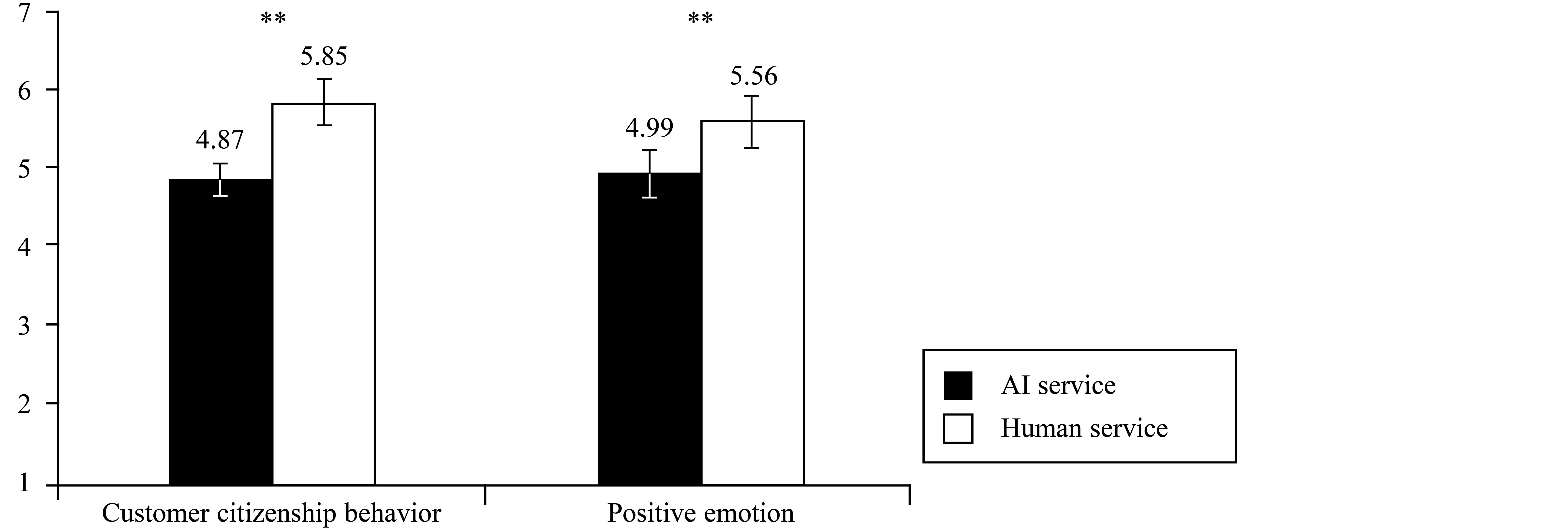

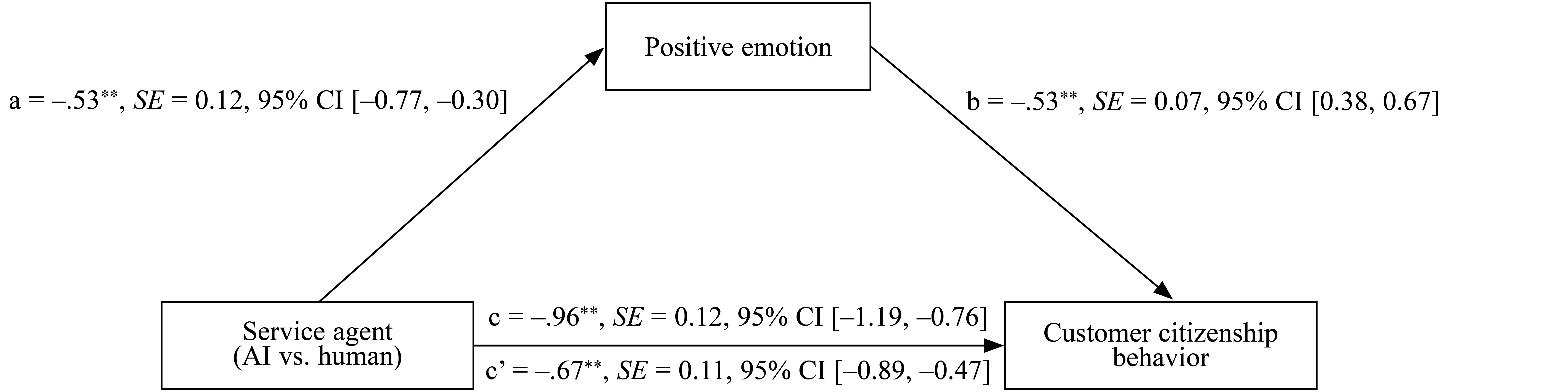

After controlling for baseline emotion (as for Study 2), the results of a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) showed that participants in the AI service setting showed significantly less customer citizenship behavior, M = 4.87, SD = 0.88, than did those in the human service setting, M = 5.85, SD = 0.78, F(1, 138) = 66.22, p < .01, η2 = .33. Participants also showed lower positive emotion in the AI setting, M = 4.99, SD = 0.91, than in the human service setting, M = 5.56, SD = 0.93, F(1, 138) = 20.33, p < .01, η2 = .13. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported (see Figure 4).

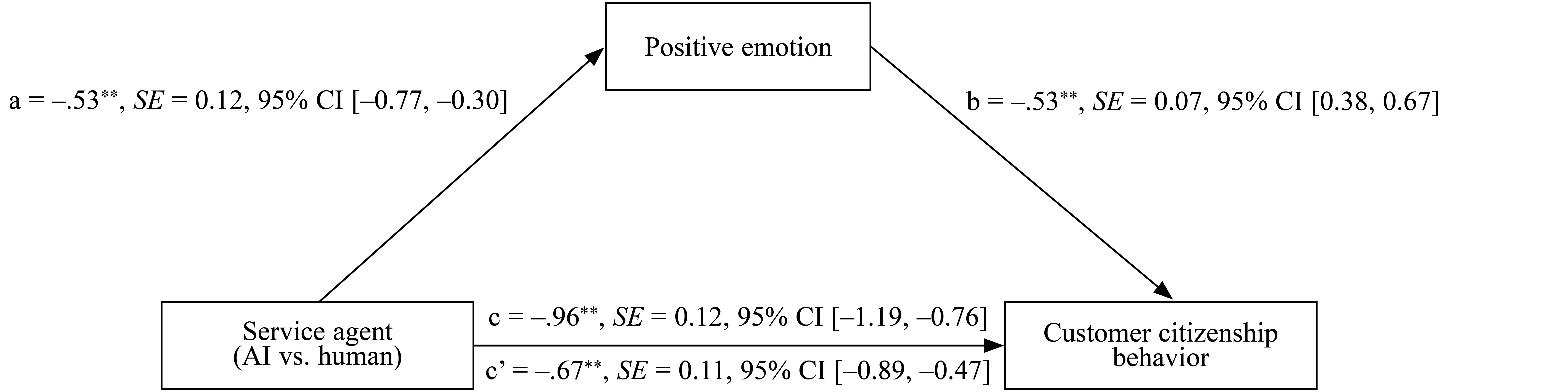

A bootstrapped mediation analysis was conducted with 5,000 resamples using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2012), with the service agent type as the independent variable, positive emotion as the mediator, customer citizenship behavior as the dependent variable, and baseline emotion as the covariate. The result revealed a significant mediating effect of positive emotion on the relationship between service agent and customer citizenship behavior, β = −.28, SE = 0.10, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−0.52, −0.12] (see Figure 5 and Appendix B). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Study 2

In Study 2 we examined whether the effect of AI service on customer citizenship behavior was moderated by brand stereotype.

Method

Participants

This experiment used a 2 (service agent: AI vs. human) × 2 (brand stereotype: competent vs. warm) between-groups design. G*Power software with a parameter for effect size of .25 at α = .05 and power = .80 (Robiady et al., 2021) was used to calculate the effect and sufficiency of the sample size. The result showed that 179 was the minimum sample size. Therefore, we recruited 200 participants, comprising 106 (53%) women and 94 (47%) men (Mage = 28.11 years, SD = 7.93) from the online survey platform www.credamo.com and randomly assigned each participant to one of the four experimental scenarios. Demographic details of participants are shown above, in Table 1.

Procedure

The warm-oriented brand was introduced in a personalized way (see Figure 6), while the competent-oriented brand was advertised as efficiency-oriented (see Figure 7).

Figure 6. Warm Brand Advertisement

Figure 7. Competent Brand Advertisement

Participants first reported their baseline emotions (see Appendix A), then they were instructed to imagine that they were planning to have a holiday and had booked a hotel on the platform. As they arrived late, they picked up the phone and tried to consult with the details on the App (see Figures 2 and 3). As in Study 1, participants reported their customer citizenship behavior (α = .83) and positive emotion (α = .91). The manipulation check for the service agent type was measured with a two-item scale (r = .90, as in Study 1), while the check for the brand stereotype manipulation was conducted using two four-item scales (competence: α = .83; warm: α = .82) adapted from Fiske et al. (2002): “Please rate the brand’s capability/competence/efficiency/intelligence/friendliness/good nature/kindness/warmth.” The first four items assessed brand competence and the latter four assessed brand warmth. Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = an extreme amount). Finally, the participants reported their demographic information.

Results

The results of an independent-samples t test showed that participants perceived higher humanless interaction in the AI service setting, M = 5.93, SD = 0.67, than in the human service setting, M = 3.24, SD = 0.55, t = 31.03, p < .05, d = 4.39. In addition, participants’ evaluation of brand competence was significantly higher for the competent-oriented brand, M = 5.76, SD = 1.02, than for the warm-oriented brand, M = 5.04, SD = 0.67, t = 5.90, p < .01, d = 0.83. Finally, participants’ evaluation of brand warmth was significantly higher for the warm-oriented brand, M = 5.86, SD = 0.94, than for the competent-oriented brand, M = 4.99, SD = 0.66, t = 7.49, p < .05, d = 1.07. Thus, both manipulations were successful.

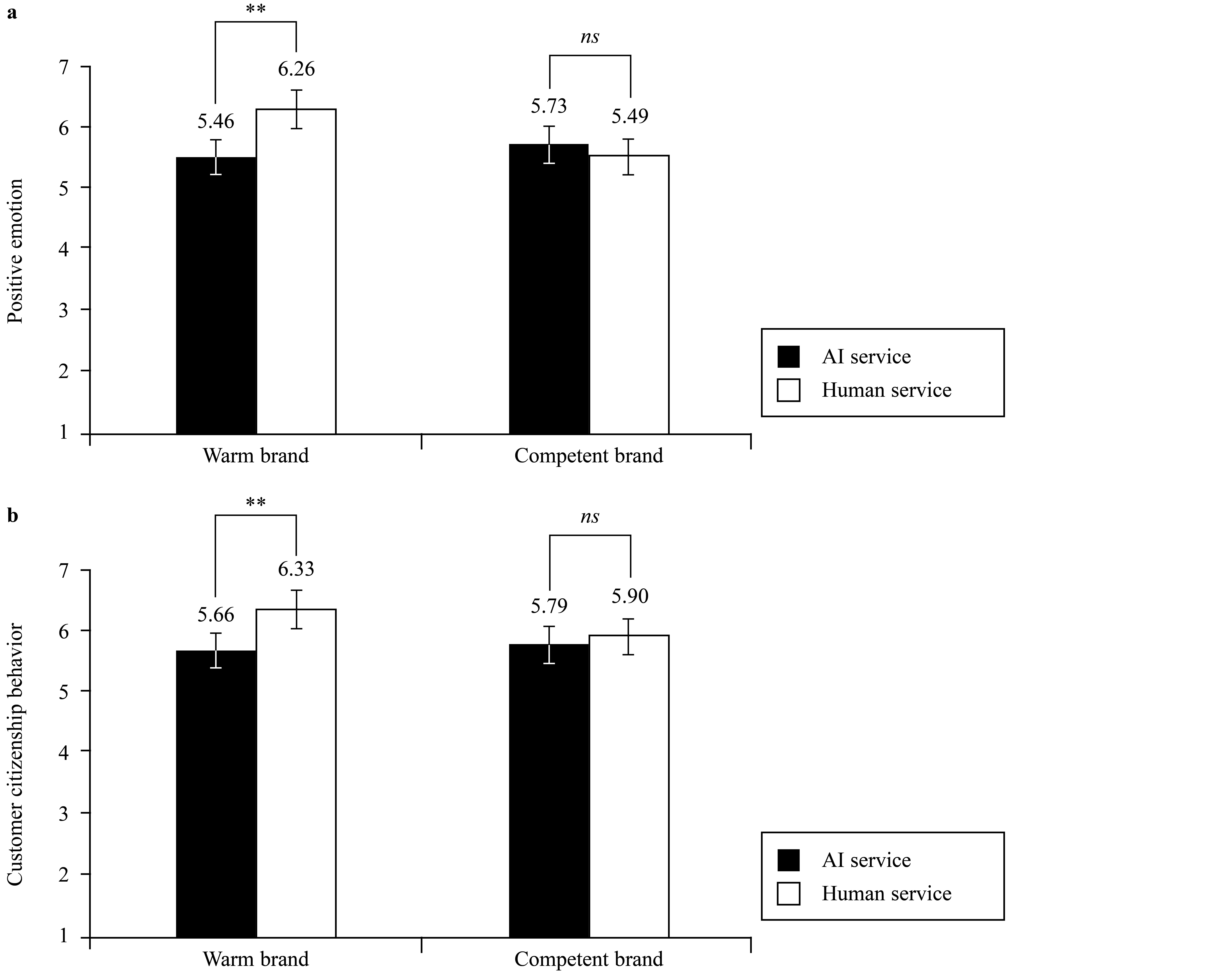

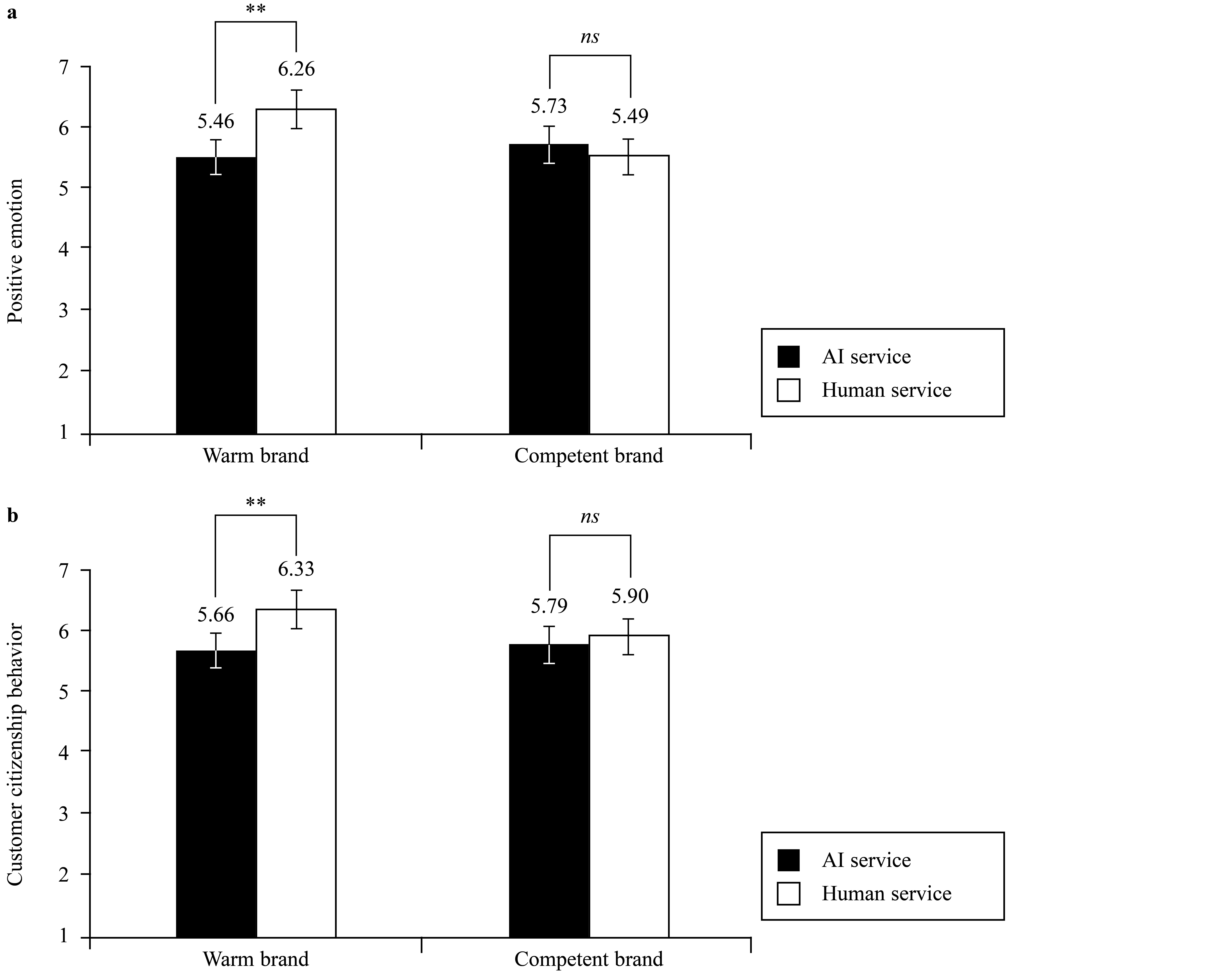

Supporting Hypothesis 1, a two-way ANCOVA demonstrated that AI service led to lower customer citizenship behavior, M = 5.72, SD = 0.60, compared to human service, M = 6.11, SD = 0.67, F(1, 196) = 20.32, p < .01, η2 = .09. AI service also led to lower positive emotion, M = 5.60, SD = 0.83, compared to human service, M = 5.87, SD = 0.86, F(1, 196) = 5.80, p < .05, η2 = .03. In addition, the interaction term of service type × brand stereotype had a significant effect on both positive emotion, F(1, 196) = 22.00, p < .01, η2 = .10, and customer citizenship behavior, F(1, 196) = 10.78, p < .01, η2 = .05. The results of a one-way ANCOVA revealed that when the brand was warm-oriented, participants reported significantly lower positive emotion for the AI service setting, M = 5.46, SD = 0.94, than for the human service setting, M = 6.26, SD = 0.69, F(1, 98) = 23.02, p < .01, η2 = .19. Participants also reported lower customer citizenship behavior for the AI service setting, M = 5.66, SD = 0.71, than for the human service setting, M = 6.33, SD = 0.27, F(1, 98) = 39.92, p < .01, η2 = .29. When the brand was competent-oriented, positive emotion did not significantly differ whether service was provided by AI, M = 5.73, SD = 0.69, or human service agents, M = 5.49, SD = 0.85, F(1, 98) = 3.01, p = .09, η2 = .03. Customer citizenship behavior likewise did not significantly differ whether service was provided by AI, M = 5.79, SD = 0.47, or human service agents, M = 5.90, SD = 0.86, F(1, 98) = 0.60, p = .44. For details see Figure 8.

Moreover, to check whether the interplay between service agent type and brand stereotype affected customer citizenship behavior through positive emotion, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis using Model 7 of the SPSS PROCESS macro with 5,000 bootstrapped resamples (Hayes, 2015). We set the service agent as the independent variable (1 = AI service, 0 = human service), brand stereotype as the moderator (1 = competent, 0 = warm), positive emotion as the mediator, and customer citizenship behavior as the dependent variable. The results indicated there was a significant indirect effect of positive emotion, Index = .36, SE = 0.13, 95% CI [0.14, 0.64]. For the warm-oriented brand, the mediating effect of positive emotion was significant, β = −.27, SE = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.46, −0.11]. For the competent-oriented brand, the mediating effect of positive emotion was nonsignificant, β = −.09, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.23]. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

General Discussion

The prevalence of AI services has aroused the interest of both business and academia. The majority of existing research has focused on consumers’ attitude and behavioral intention toward AI services, such as consumer preference and adoption intentions (Zhu et al., 2022). While this body of literature has provided valuable insights, there has been limited research on how AI services shape consumer extrarole behaviors. Scholars have also called for further studies of the behavioral consequences of AI services (Fan et al., 2022). Building upon existing research, we have shed light on how AI services affect consumer psychological states and social behaviors. The two empirical studies in this paper consistently demonstrate that there is a negative correlation between AI services and consumer citizenship behaviors, which supports the findings of Y. Zhou et al. (2022) that human–chatbot interaction impairs charitable donation. These results suggest that AI chatbots cannot fully replace the role of human agents, which aligns with the findings of Fan et al. (2022) regarding the potential dark side of AI services.

In addition, we have demonstrated the mechanism of this effect based on positive emotion, using emotional spillover theory. This expands the explanatory path of customer citizenship behavior from cognitive processing (Song et al., 2022) to mental processing. Furthermore, this study contributes to understanding of customers’ emotional response to AI services by investigating brand stereotype as a boundary condition. The AI–warmth paradox presents a significant challenge in marketing experience products that are consumed primarily for the experiential value they provide, rather than for their functional utility, as AI chatbots are driven by technology, which is often perceived as competent and cold (Wirtz et al., 2018). This lack of human touch calls for complementation from the brand’s value. Our study aligns with the work of Ruan and Mezei (2022) in exploring the effectiveness of AI chatbots in experience product settings, considering the interplay with brand characteristics.

This study also has critical implications for practice. While previous research has emphasized that brand warmth has a stronger impact on consumer behaviors than does brand competence (Kolbl et al., 2020), our findings demonstrate that brand competence is particularly helpful for AI services. The negative effects of AI service on customers’ positive emotion and behavior are mitigated when the brand is perceived as competent rather than warm. Established warm brands can consider reserving human service for high-contact positions if they choose to adopt AI services. On the other hand, start-up companies can advertise their brands as competent to emphasize the fully automatic nature of their services. Regardless of the situation, service providers should strive to compensate for the loss of social contact in AI services to enhance customer well-being.

There are several limitations to this research. First, we considered only the binary interaction between consumers and service providers. With the emergence of the service triad (Odekerken-Schröder et al., 2021), future studies could explore whether the combination of human staff and AI chatbot can provide a better service experience. Second, we focused primarily on customer citizenship behavior. Future studies could examine the generalizability of these findings to green customer citizenship behavior (Zhang et al., 2022). Additionally, the perception of interaction with AI services can vary among individuals. For instance, individuals with a tendency toward social avoidance, which is characterized by a desire to avoid being with other people (Watson & Friend, 1969), may have stronger positive emotion toward AI service. Therefore, future research could explore the boundaries of this effect among different individuals.

References

Appendix A

Differences in Emotion at Pre- and Posttest

Note. AI = artificial intelligence.

Appendix B

Conditional Indirect Effects of the Moderated Mediation Model

Note. AI = artificial intelligence.

Table 1. Participants’ Demographic Profile

Note. Numbers in parentheses are the percentage of the total sample. CNY 1.00 = USD 0.14.

Figure 2. Artificial Intelligence Service Scenario

Figure 3. Human Service Scenario

Figure 6. Warm Brand Advertisement

Figure 7. Competent Brand Advertisement

Note. AI = artificial intelligence.

Note. AI = artificial intelligence.

Haiquan Chen, School of Management, Jinan University, No. 601, Huangpu Avenue, Tianhe District, Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China, 510632. Email: [email protected]