Emotion experience and regulation in undergraduates following social rejection: A daily diary study

Main Article Content

We used a 30-day daily diary assessment method to examine the within-person associations between social rejection, emotional experiences, and emotion regulation strategies in a sample of 34 college students. Taking emotional experience as the dependent variable, we explored and analyzed cumulative and hysteresis effects using a random regression coefficient model. The results showed that situations of social rejection tended to induce negative emotional experiences, for which college students mostly adopted attention transfer strategies. In contrast, positive emotional experience increased in situations of social acceptance, and college students mostly adopted cognitive reappraisal strategies in this setting. Further, cognitive reappraisal strategies had time accumulation and overlapping effects on individual positive emotional experiences, and attention transfer strategies had a lag effect on individual emotional experiences. These findings advance understanding of the negative affect–emotion regulation association among individuals exposed to social rejection.

Method

Participants

We recruited 34 students from a college in China, comprising 14 men and 20 women with an average age of 20.6 years (SD = 1.64, range = 19–23). Before the study started, the participants completed an informed consent form, indicating that they understood the survey procedure and test content and agreed to take part. The sample size was determined based on an a priori power analysis, which showed that 27 participants were required to detect a small-to-medium-sized interaction effect (f = .80) with an alpha value of .05 and power of .80. Therefore, this study was sufficiently powered.

Procedure

This study used continuous daily data acquisition tracking for 1 month. The participants were required to accurately record daily life situations (key characters and key events), rate their emotion regulation, and evaluate their emotional experiences at the end of the day. To ensure high-quality data and timely recording and evaluation, they used smartphones and were prompted to send their completed measures for recording and evaluation at 12 pm daily. The reporting rate was 100%. No incentives were provided for participation.

Measures

Emotional Experience Scale

The emotional experience of each social situation was scored using an 8-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (very unhappy) to 7 (very happy). The overall emotional experience in each day was scored using an 8-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Considering that the emotional experiences induced by daily life situations are complex, diverse, and cannot be measured by a single basic emotion, the emotional experience scale items in this study included happiness, excitement, pleasure, surprise, anxiety, anger, sadness, guilt, and shame. The average scores for positive and negative emotions were calculated. Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability in this study was .87.

Daily Life Situations Surveys

The participants recorded the social situations they experienced in daily life, including the time, place, person(s) involved, and process. They were allowed to use alternative symbols and patterns to simplify relevant details, such as the names of key figures and important objects, for reasons of privacy. The influence of social context on emotion experience was scored by participants using an 8-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Upon completion of the recording, social situation classification was coded by two psychology postgraduates. If the coding results of the two sides were inconsistent, they were required to reach an agreement after discussion.

Daily life situations were divided into social rejection and social acceptance categories. Social rejection situations refer to settings in which individuals are ignored or rejected by others and in which they might experience neglect, negation, or rejection. Social acceptance situations refer to settings in which individuals feel accepted or are shown concern and in which they might experience attention, affirmation, or acceptance.

Emotion Regulation Strategy

After collecting the specific descriptions of participants’ emotion regulation in each event, emotion regulation strategies were judged and classified by two coders. With this index, emotion regulation was divided into the elements of cognitive reappraisal, attention transfer, concealment restraint, keeping calm, disclosure, and enjoyment (English et al., 2017). Individuals use the strategy of cognitive reappraisal to assign new meanings to situations, thereby regulating their emotional responses and behavioral tendencies. Attention transfer refers to the strategy by which an individual’s attention selectively refocuses on other situations and things, thereby transferring the focus of induced emotion and weakening the intensity of a particularly emotional experience. Concealment restraint refers to the strategy whereby individuals do not express their real emotions or force their suppression. Keeping calm refers to the individual facing emotional events and remaining calm. Disclosure entails revealing and venting about one’s emotional experiences, while enjoyment refers to recalling or experiencing positive emotions for a long period.

Data Analysis

After data collection and coding, we used SPSS 20.0 and HLM 6.08 software for statistical processing.

Results

The Emotional Experiences of College Students in Daily Life Situations

The college students experienced acceptance situations 2.20 ± 0.17 times per day and rejection situations 1.87 ± 0.20 times per day. The average positive emotional experience score was 3.16 ± 0.24, while the score for negative emotional experience was 1.58 ± 0.22. A correlation analysis revealed that frequency of refusal situations in a day was significantly and positively correlated with negative emotional experiences (r = .73, p < .001). In analyzing the temporal changes in emotional experience by repeated measures analysis of variance, we found no significant differences in positive emotional experience, F(30, 982) = 1.24, p = .17, but there was a significant difference in negative emotional experience, F(30, 982) = 1.53, p < .05, η2 = 0.05. We also found that the negative emotional experiences of the first 3 days, the 5th day, the 7th day, the 11th day, and the 16th day were all significantly higher than those of other time points. Furthermore, the score on the 29th day was significantly lower than those of the other time points, indicating fluctuations in the negative emotional experiences of college students in daily life.

College Students’ Application of Emotion Regulation Strategies in Daily Life Situations

The influence indices of acceptance and rejection situations in the study were 3.09 ± 0.22 and 2.91 ± 0.33, respectively. These indicate that emotional situations induced a certain degree of emotional experience and needed to be adjusted accordingly.

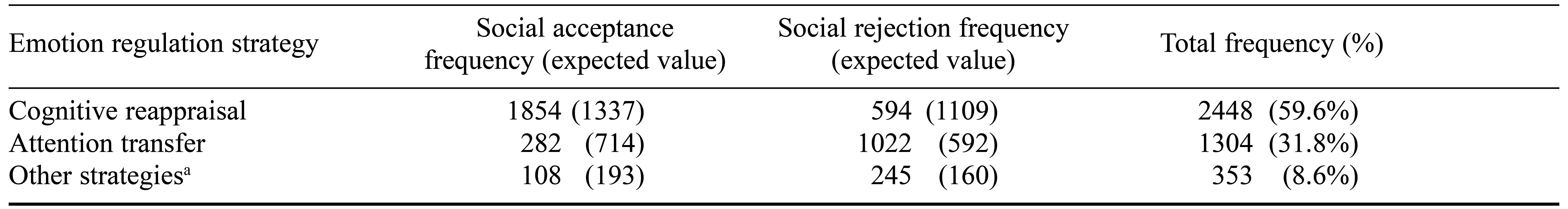

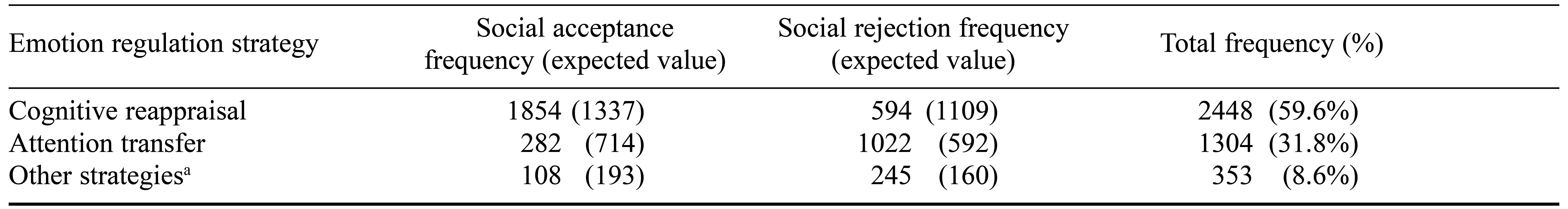

As shown in Table 1, college students used a cognitive reappraisal strategy the most frequently (59.6%), followed by an attention transfer strategy (31.8%). Statistical analysis yielded a value of χ2 = 1012.78 (df = 2, p < .001), indicating that the emotional context of daily life was significantly associated with the use of emotion regulation strategies; specifically, college students tended to adopt attention transfer strategies in social rejection situations and cognitive reappraisal strategies in social acceptance situations.

Table 1. Emotion Regulation Strategies in Social Situations in Daily Life

Note. aOther emotion regulation strategies included concealment restraint, keeping calm, disclosure, and enjoyment.

Cumulative Effect of Emotion Regulation on College Students’ Emotional Experiences in Daily Life Situations

The cumulative effect of college students’ emotional adjustment on their emotional experiences in daily life was analyzed using a random regression coefficient model. The first layer consisted of the sampled daily data and the second layer was the zero model form for individual data. The specific mathematical models were as follows:

First layer: Emotional experience dj = β0j + β1j × Emotion regulation dj + εdj

Second layer: β0j = γ00 + μ0j, β1j = γ10 + μ1j

where β0j represents the average score of emotional experience without emotion regulation, and β1j is the influence coefficient of emotion regulation on emotional experience. The size of the coefficient indicates the influence of emotion regulation on emotional experience.

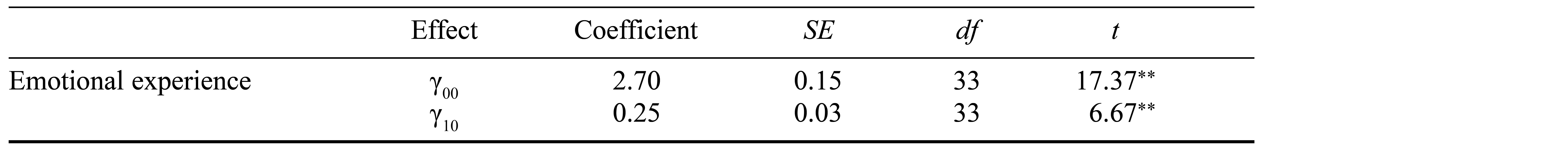

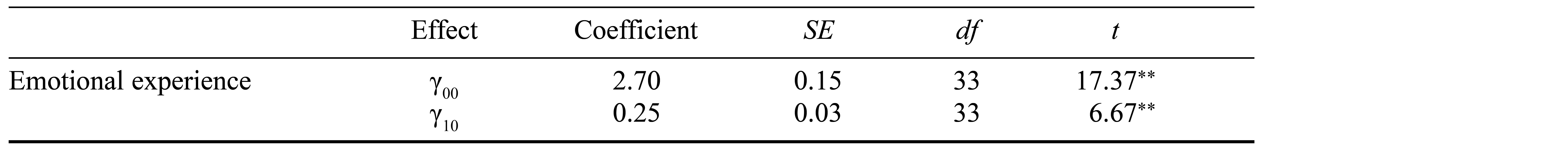

As shown in Table 2, the effect of cognitive reappraisal on positive emotional experience was significant (the moderating effect of cognitive reappraisal was γ10 = 0.25, p < .001), whereas the effect of attention transfer was not significant. Therefore, cognitive reappraisal affected college students’ positive emotional experiences in emotional situations. Individuals’ use of cognitive reappraisal also had a time-cumulative effect on their subjective positive emotional experiences.

Table 2. Effect of Cognitive Reappraisal on Emotional Experience

Note. ** p < .001.

Lag Effect of College Students’ Emotion Regulation on Their Emotional Experiences in Daily Life Situations

We used a time-lagged multilayer linear analysis model to further explore whether college students’ emotion regulation had a lag effect on their positive emotional experiences in daily life. Emotion regulation and emotional experiences of the previous day were used as the independent variables. The dependent variable was the score for emotional experience on the following day. A zero model was used for analysis.

For emotional experience and emotion regulation in emotional situations, two time-lagged multilayer linear analysis mathematical models were devised as follows:

First layer: Emotional experience d + 1j = β0j + β1j × Emotional experience dj + β2j × Emotion regulation dj + εdj

Second layer: β0j = γ00 + μ0j, β1j = γ10 + μ1j, β2j = γ20 + μ2j

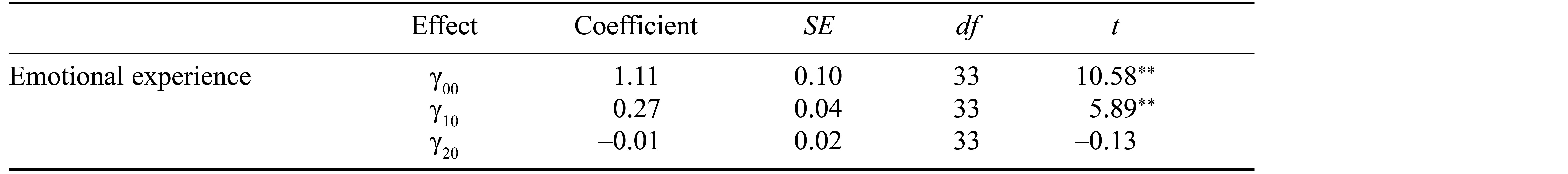

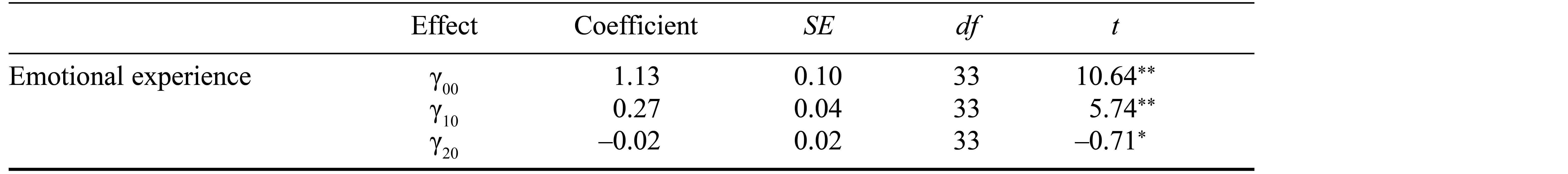

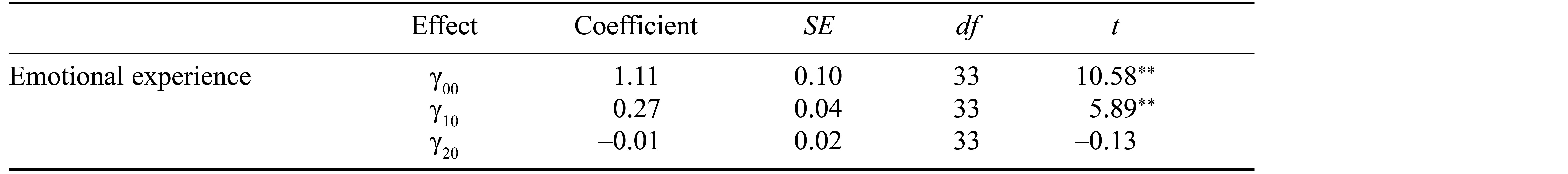

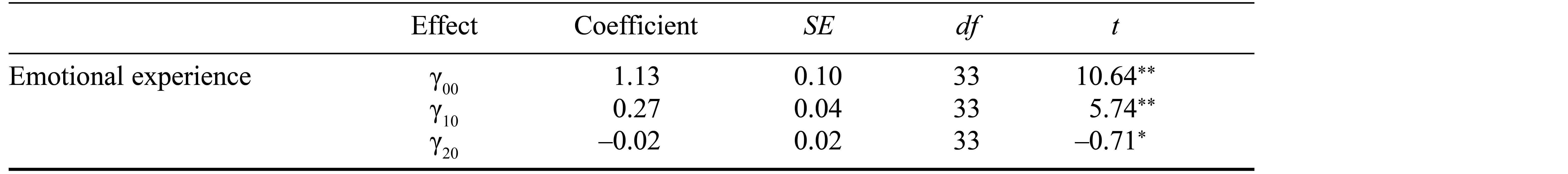

As shown in Tables 3 and 4, in daily life situations college students’ emotional experiences showed a lag effect (γ10 = 0.27, t = 5.74, p < .001). Furthermore, use of the attention transfer adjustment strategy on the previous day significantly affected the emotional experience of the next day (γ20 = −0.02, t = −0.71, p < .05), indicating a lag effect for the use of the attention transfer strategy.

Table 3. Time-Lagged Changes in Cognitive Reappraisal Strategy and Emotional Experience

Note. ** p < .001.

Table 4. Time-Lagged Changes in Attention Transfer Strategy and Emotional Experience

Note. * p < .05. ** p < .001.

Discussion

Analysis of Daily Life Situations and Emotion Regulation

The results of this study showed that emotional situations in daily life are related to emotional experience and that rejection situations are positively correlated with negative emotional experience. Social rejection is experienced widely in people’s daily lives and threatens the sense of belonging, which is one of the most basic needs of individuals (Luo et al., 2012; Williams, 2007). Our results reveal that individuals tend to use cognitive reappraisal in acceptance situations and attention transfer in rejection situations.

Emotion regulation preference in daily life has attracted the attention of emotional psychology researchers, who have discussed this concept in terms of cognitive behavior and proximity avoidance. Some researchers believe that rejection situations in daily life differ from temporary, virtual rejection situations induced in a laboratory setting. In particular, the former may have greater long-term effects, which, in turn, may affect individuals’ self-control and weaken their ability to choose and use emotion regulation. Furthermore, individuals pay greater attention to weakening the impact of negative emotions and restoring emotional, cognitive, and behavioral self-regulation (Riva et al., 2014). In the context of rejection, individuals tend to use attention transfer, which initially weakens the influence of emotional stimuli and then gradually eliminates the negative impact.

Some studies have found that among individuals of Chinese cultural background, the choice of emotion regulation strategies is closely related to interpersonal situations. When people have good interpersonal relationships they tend to use cognitive reappraisal, whereas when they are in poor interpersonal relationships they tend to use emotion regulation strategies (Li & Lu, 2005). The college students in this study tended to use the emotion regulation strategy of attention transfer in the context of rejection, which is a positive and healthy emotional coping method.

Cumulative Effect of College Students’ Emotion Regulation on Their Emotional Experiences in Daily Life Situations

Our results show that cognitive reappraisal significantly affects individuals’ positive emotional experiences in daily life situations. In particular, the use of individual cognitive reappraisal in the context of rejection has a cumulative effect on positive emotional experience. Cognitive reappraisal entails modifying one’s emotional experiences by mentally separating oneself from unfavorable circumstances and altering one’s cognitive interpretation (Grezellschak et al., 2015). Furthermore, cognitive reappraisal is a regulatory strategy of prior attention, which involves modifying a possible negative emotional experience by readjusting one’s cognitive concept of an external emotional situations or endowing situations with new meaning. This finding is consistent with that presented in previous studies (see, e.g., Yuan et al., 2015). Therefore, our results reveal that individuals of Chinese cultural background may effectively reduce the negative impact of negative emotions through cognitive reappraisal.

The inertia emotion strategy formed by individuals can reflect the time superposition effect of emotion regulation strategies on emotional experience. When the intensity of an irrational emotional experience is adjusted, corresponding physiological indicators and reactions of discomfort, including skin temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate, are also adjusted and stabilized (Kreibig, 2010). On the whole, cognitive reappraisal has a cumulative protective effect on the physical and mental health of individuals in situations of rejection in daily life.

Lag Effect of College Students’ Emotion Regulation on Their Emotional Experiences in Daily Life Situations

The results reveal that attention transfer has a lag effect in daily life situations, in which the use of emotion regulation during the previous day significantly affects the emotional experience of the following day. Attentional shifting involves directing one’s attention away from the current context toward alternative stimuli, thereby attenuating the impact of certain adverse emotional experiences (Grezellschak et al., 2015). Attention transfer, which is the most commonly used emotion regulation method in people’s daily lives (Brans et al., 2013), reduces the negative impact of negative emotions on the time axis of emotion occurrence. Here, individuals selectively remove their attention from the current emotional situation or focus on cognitive operation activities unrelated to the emotional situation (continuous addition and subtraction operations). In doing so, they deviate from the point of emotional focus and prevent or weaken the occurrence and persistence of negative emotional experiences.

Attention transfer has proven to be the most effective strategy when negative emotions induced by emotional situations are fully exposed and responded to and when the rapid regulation of their intensity is required (Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005). In the laboratory context the time interval between the first presentation of emotional stimuli and the second presentation of situations is relatively short, and the effect of repetition of emotional stimuli in daily life situations may be small. In this study the frequency of daily life events was recorded in the unit of a day and the effects of the corresponding emotion regulation strategies differed from those seen in a laboratory setting. We found that rejection situations in daily life induced negative emotional experiences, prompting individuals to use attention transfer adjustment strategies. Such strategies have both a timely effect and an overall lag effect on negative emotional experiences.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

In terms of limitations, our findings may not be generalizable to other cultural or educational contexts because our sample was composed solely of Chinese college students. Furthermore, this study was small in scale and caution is recommended in drawing wider conclusions based on our findings. Nonetheless, the daily diary method has important advantages in exploring the effects of college students’ daily emotion regulation in the context of social rejection.

References

Table 1. Emotion Regulation Strategies in Social Situations in Daily Life

Note. aOther emotion regulation strategies included concealment restraint, keeping calm, disclosure, and enjoyment.

Table 2. Effect of Cognitive Reappraisal on Emotional Experience

Note. ** p < .001.

Table 3. Time-Lagged Changes in Cognitive Reappraisal Strategy and Emotional Experience

Note. ** p < .001.

Table 4. Time-Lagged Changes in Attention Transfer Strategy and Emotional Experience

Note. * p < .05. ** p < .001.

The authors acknowledge support from the Research Foundation for Advanced Talents (WGKQ201702021) and the Ministry of Education, Humanities, and Social Science Research Funds (13YJC190010).

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Dengfeng Xie, Education Science College, West Anhui University, Postal No. 1 Yunlu Road, Yu’an District, Lu’an City 237012, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected]