What kinds of online video advertising music do people like? A qualitative study

Main Article Content

If consumers like the music in an advertisement, this is conducive to their forming a positive response. To find out what kinds of advertising music people like we conducted semistructured in-depth interviews with 20 participants in China, then analyzed the content through thematic analysis. We found that consumers liked music that they perceived as having good advertising functions, acceptable artistic qualities, attractive characteristics (e.g., interesting, positive, easy to remember, distinctive), and which had the ability to evoke positive affect and feelings. This study supplements previous investigations into advertising music from the perspective of consumers. On the basis of our findings, we provide suggestions on selecting music for advertisements that consumers find likable.

The influence of advertising music on consumers has been widely studied (Allan, 2006; Chou & Lien, 2010; Chou & Singhal, 2017; Lavack et al., 2008), including the effects of three types of integration of popular music in advertisements (original lyrics, altered lyrics, and instrumentals) on attention and memory (Allan, 2006), the influence of brand-congruent music on brand attitude specific to the differences caused by the consistency of music (Lavack et al., 2008), the effects of songs’ nostalgia (Chou & Lien, 2010), gender match-up between singer and audience (Chou & Singhal, 2017), and the impact of music tempo on consumers’ attitudes toward the brand (Stewart & Koh, 2017). Gorn (1982) discovered that consumers’ product preferences may be affected by whether they are listening to liked or disliked music, and Tom (1995) partly replicated this finding. Vermeulen and Beukeboom (2016) carried out three experiments to investigate how single-pairing of background music with an advertised product can condition consumer choice behavior, and found that single, short, and simultaneous pairing of a product with liked/disliked music may affect consumers’ choice. However, the effects were weaker than those originally reported by Gorn when various factors were controlled for (e.g., confounds in the musical stimuli, between-participant contamination). Gorn’s research results are controversial because although some studies support them, others provide only partial support (Tom, 1995; Vermeulen & Beukeboom, 2016) or no support (Kellaris & Cox, 1989; Pitt & Abratt, 1988). Even so, matching preferred music with products is of significance for consumers’ decision making because the reported inconsistencies may be caused by other factors.

Moreover, if advertisers use consumers’ favorite music to promote products, the benefits are not limited to a positive impact on consumers’ choices. For example, pairing a brand with liked music can significantly improve general brand and product evaluations (Vermeulen & Beukeboom, 2016), and it has been found that the likability of music has significant positive effects on consumers’ attitude toward the advertisement and the brand (Galan, 2009). Thus, if advertisers want to enhance advertisement effectiveness, they should use music that consumers like.

However, it is not completely clear from the extant research what kinds of advertising music consumers like. Although suggestions can be obtained from previous studies (e.g., Craton & Lantos, 2011; Finnäs, 1989; Peretz et al., 1998), and scholars have clarified the importance and positive influences of favorite music (Bierley et al., 1985; Galan, 2009; Gorn, 1982; Tom, 1995; Vermeulen & Beukeboom, 2016), there is a lack of research on which advertising music consumers like. The extant literature mainly covers which characteristics of music may get a good response from consumers, and some concepts are helpful for exploring what advertising music consumers like. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the kinds of advertising music that consumers like.

Moderate Familiarity

It has been found that repetition of an unfamiliar melody increases consumers’ fondness for it (Peretz et al., 1998), whereas for simple and well-known music repetition can quickly lead to a decline in preference (Finnäs, 1989). Therefore, a piece of music that is more familiar is not necessarily better in inducing liking. Indeed, “the association between familiarity and liking is by no means linear” (Swaminathan & Schellenberg, 2015, p. 193). After studying music in service environments, Herrington (1996) suggested that service providers should choose music that is “familiar yet still fresh to patrons” (p. 38). Chou and Lien (2010) conducted a study with a sample of young people and found that a popular song that had been released during the participants’ childhood may be a good choice for advertising music because it can arouse feelings of nostalgia, leading to a good mood and favorable brand attitude.

Fit

Researchers have found that musical fit influences product choice. North et al. (1997) reported that more French than German wine was sold when French music was played in-store, and more German than French wine was sold when German music was played. In 2004, North et al. conducted two studies on musical fit. The first study indicated that musical fit enhanced recall of advertised products and brands, and increased both participants’ ratings of how much they liked the advertisement and their likelihood of buying the advertised product. The second study found that voice fit could also promote recall of specific product claims, increase liking of advertisements, and raise the likelihood of purchasing the advertised product. In high-cognition advertisements, congruent music positively influences consumers’ attitudes toward an advertisement and brand (Lavack et al., 2008). The use of highly relevant lyrics facilitates the production of favorable advertisement execution-related thoughts, which can affect attitudes toward the advertisement both directly and indirectly, the latter through the mediator of good mood (Chou & Lien, 2010). These results emphasize that advertising music does not exist in isolation; rather, to impress consumers it must be matched with other elements of the advertisement.

Music Preference

Music preferences are an important factor in choosing advertising music because they “represent liking for individual pieces or specific genres of music, which reflect basic approach or avoidance responses” (Swaminathan & Schellenberg, 2015, p. 193). Stronger preference tends to be aroused by “(a) fast tempos and distinct rhythm, (b) coherent melodies, (c) absence of pronounced dissonances, and (d) a moderate degree of complexity” (Finnäs, 1989, p. 1). Music preferences may be influenced by the cognitive, emotional, and cultural functions of music, by physiological arousal, and by familiarity (Schäfer & Sedlmeier, 2010). Since the preferences of different populations may vary greatly with social and cultural habits and fashions (Finnäs, 1989), it is impossible to find music that all consumers prefer. Therefore, our goal was instead to identify music that most consumers may like, which means it is important to find common likable points in advertising music. If a comprehensive evaluation can be made of whether a piece of music is good or bad in the minds of consumers, the selection of advertising music will be simplified.

Attitude Toward Advertising Music

To identify the causes of potential negative consumer response to music in broadcast advertisements, Craton and Lantos (2011) introduced a new consumer response variable: attitude toward advertising music (AAM). As a significant component of attitude toward an advertisement, AAM refers to “a predisposition to respond in a favorable or unfavorable manner to an ad’s music during a particular exposure occasion” (Craton & Lantos, 2011, p. 401). It is “essentially what the consumer perceives, thinks, and feels in response to an ad’s music—that is, how the consumer consciously experiences the music” (Craton et al., 2017, p. 21); thus, listening situation, musical stimulus, listener characteristics, and advertising processing strategy can affect a consumer’s AAM (Lantos & Craton, 2012). Raja et al. (2018) constructed a multi-item scale to measure consumers’ AAM with congruity, music appeal, and utilitarianism, but AAM is more concerned with consumer response than with the music itself.

Past studies have provided some good suggestions for choosing advertising music, but we believe more work is needed. First, studies need to be conducted from the perspective of consumers so that aspects that consumers care about and that have not yet been discussed by researchers are not missed. Second, in the extant literature, some concepts in the advertising music field do not directly point to music. For example, familiarity with music depends on consumer experience. Therefore, we adopted a qualitative research method to explore consumers’ thoughts in detail. We hoped to find indicators directly related to the characteristics of the music itself in order to provide advertisers with a very practical reference when selecting music.

Method

Thematic Analysis

Many previous studies on advertising music have adopted the method of combining experimental and quantitative analysis approaches (e.g., Kellaris et al., 1993; Lavack et al., 2008; Park et al., 2014); thus, more qualitative advertising research is needed (Belk, 2017). De Pelsmacker (2021) pointed out that there has been very little qualitative research on the advertising discipline, although qualitative research is highly regarded and widely published in other disciplines. Thus, we adopted a qualitative research approach because of its exploratory nature, so that the phenomena could be understood and interpreted from the participants’ point of view (Hussain et al., 2020; Priporas et al., 2017).

Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes within data whereby the data set can be minimally organized and described in rich detail (Braun & Clarke, 2006). It is a qualitative analytic method widely used in psychology (Braun & Clarke, 2006) that has proven to be applicable in the field of advertising (Hussain et al., 2020). Braun and Clarke (2006) illustrated the flexibility of this method, which is not wedded to a pre-existing theoretical framework; rather, it is a data-driven process that can be compatible with essentialist as well as constructionist paradigms within psychology. We adopted the following six steps of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006): (1) become familiar with the data, (2) generate initial codes, (3) search for themes, (4) review themes, (5) define and name themes, and (6) produce the report. In addition, a selection of participants’ pertinent words and verbatim quotations was reported to provide clarity in interpreting meaning and to enhance validity (Middleton et al., 2020).

Procedure

We chose online video advertisements as the conversation object of our consumers during the interviews. There have been many studies about music in radio and television advertisements (Galan, 2009; Kellaris et al., 1993; Kupfer, 2017; Lalwani et al., 2009; Park et al., 2014), but, to our knowledge, there is a lack of studies about music in online video advertisements. As information technology has continued to develop, many online video advertisements are now being released through mobile devices. In the process of data collection in this study, for convenience, participants watched online video advertisements with music on laptops, tablets, or cell phones.

Data were collected through semistructured in-depth interviews. Each participant was interviewed individually, and most of the interviews lasted between 40 and 60 minutes. The total length of all the interviews was about 850 minutes. The basic procedure of the interview was as follows: (1) Ask respondents to talk about their favorite advertising music and why they like it. This step allows consumers to recall their favorite advertising music and its characteristics, and, at the same time, they can promptly connect with the topic. (2) Invite respondents to watch three video advertisements with music and share their thoughts about whether they like it and, if so, why. (3) Ask respondents to summarize the common characteristics of the advertising music they like. (4) Ask for basic demographic information, including age, level of education, music preferences, and occupation. During the entire process, questions were added according to the respondents’ answers.

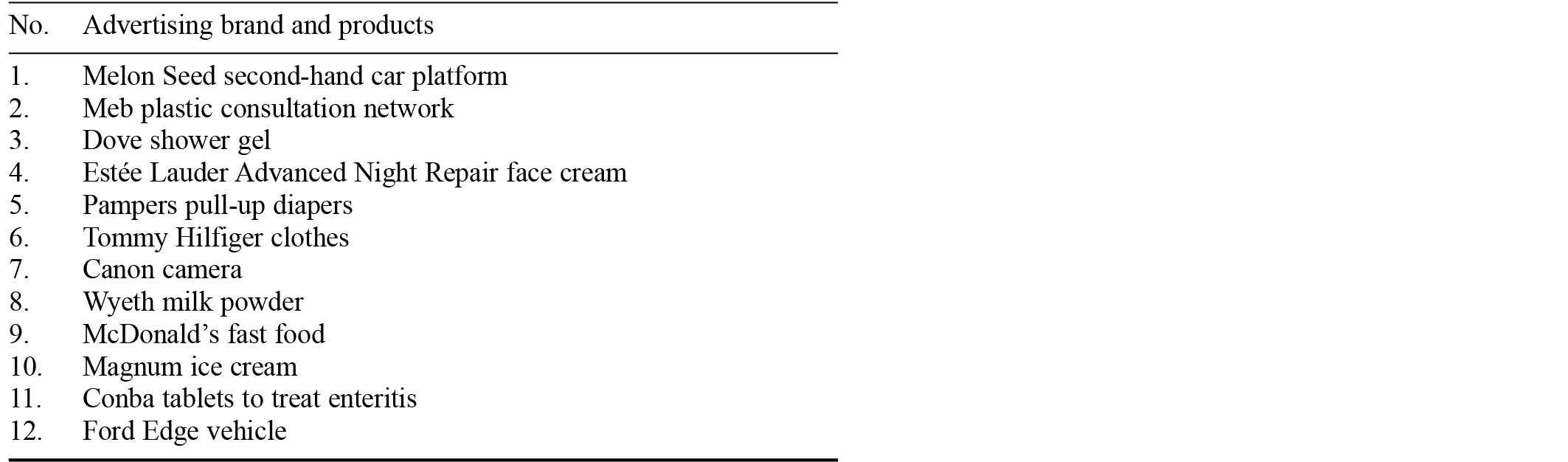

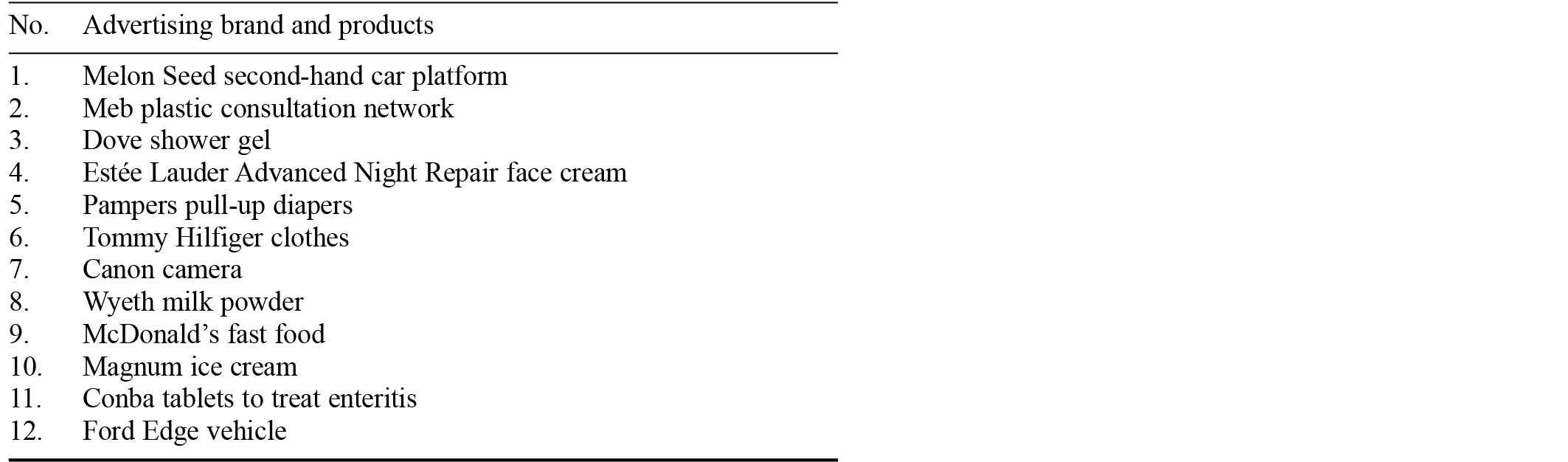

The interviewees were asked to randomly choose either (a) three advertisements (usually < 1 minute each in duration) on the Internet via their cell phones/tablets/laptops or (b) three of our recorded advertisements, and watch these on their cell phones. We recorded 12 video advertisements (see Appendix) from three popular Chinese video platforms: Tencent, iQIYI, and Youku. Four of the 20 respondents randomly selected online advertisements, and the rest watched the advertisements we had recorded. Using the recorded advertisements enabled the interviews to proceed smoothly even in the case of a poor network signal.

Participants

Twenty participants (nine men and 11 women) were recruited through snowball sampling and all had heard of advertising music before. The interviewees (Mage = 31.40 years, SD = 10.46, range = 20–56) were recruited from March 2019 to February 2021. Participants were informed of the purpose of this research, their names were coded to ensure anonymity, and the interviews were recorded with their permission. All records were transcribed verbatim by the interviewer to avoid ambiguity.

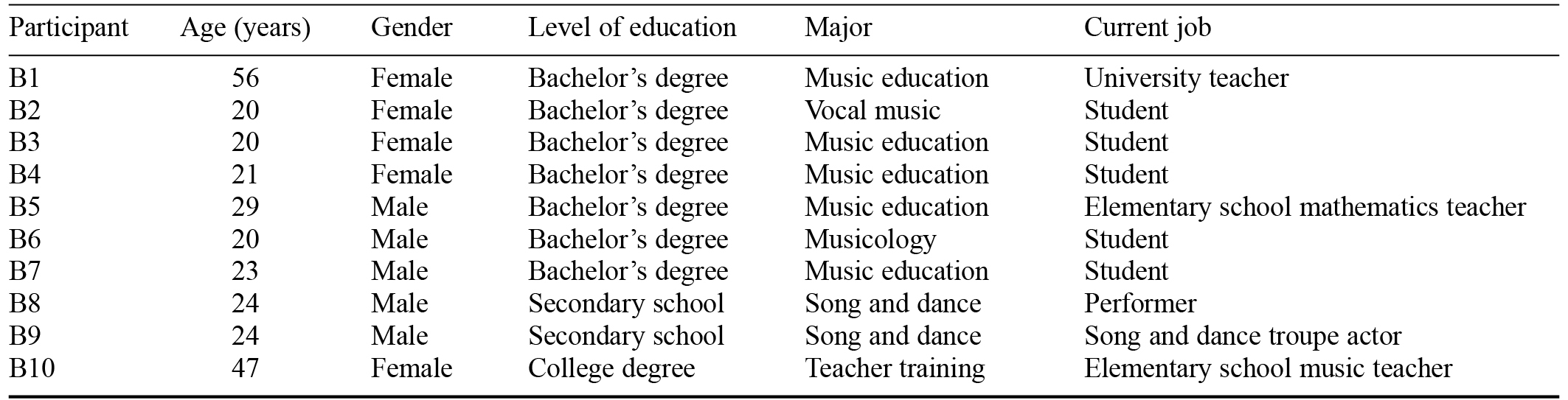

Participants who had received systematic music education were coded as B1–B10, and those who had not were coded as A1–A10. The reasons for including two types of interviewees in our sample are as follows: (a) Those who have (vs. have not) received systematic music education can more accurately express and describe their views concerning music knowledge; (b) Among consumers as a whole, only a few have received systematic music education. Thus, the perspectives of those who have not are still very important and representative.

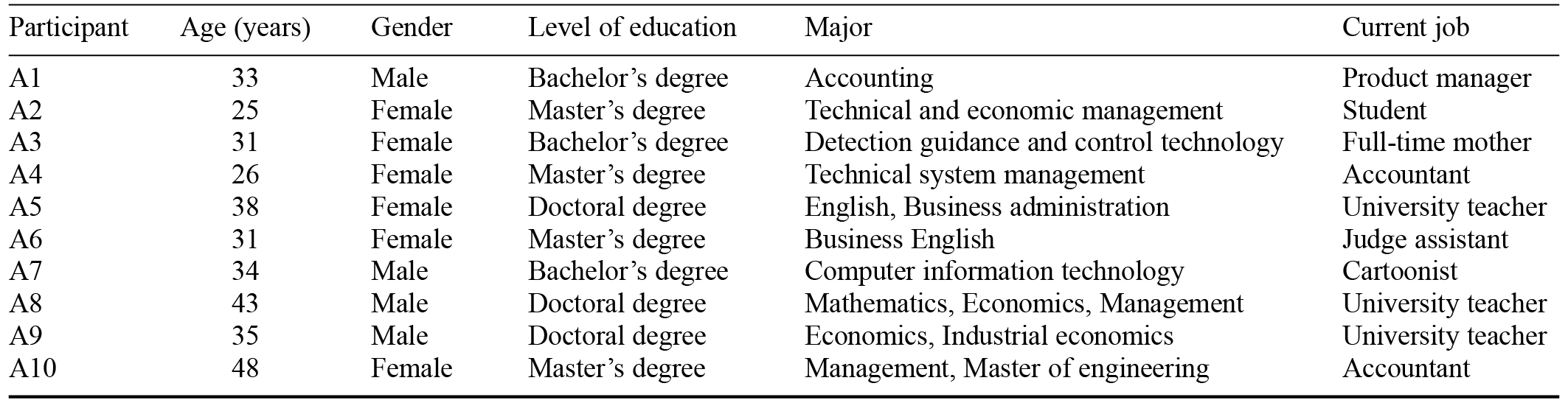

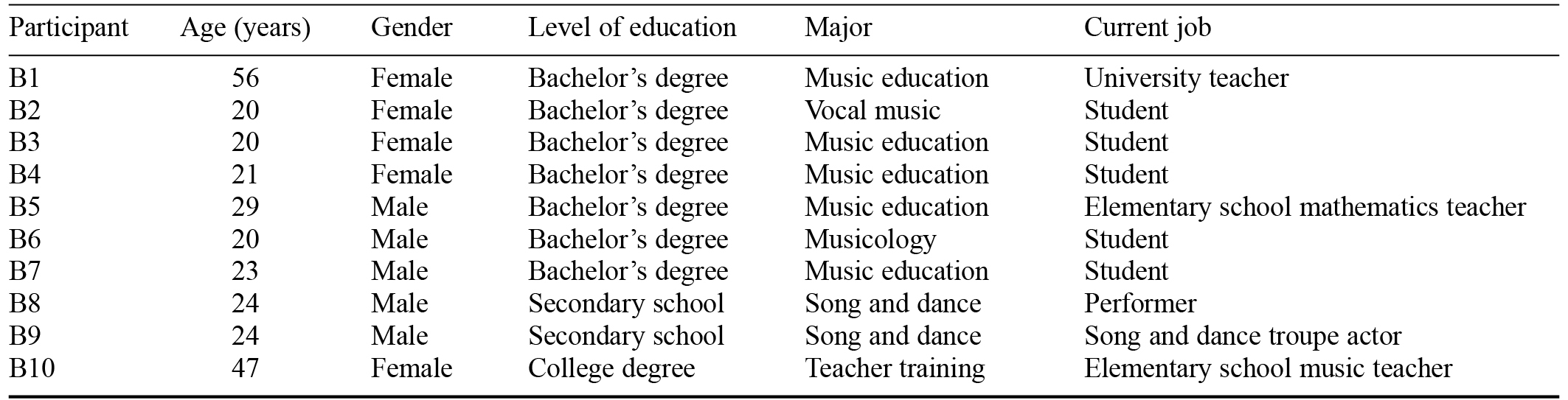

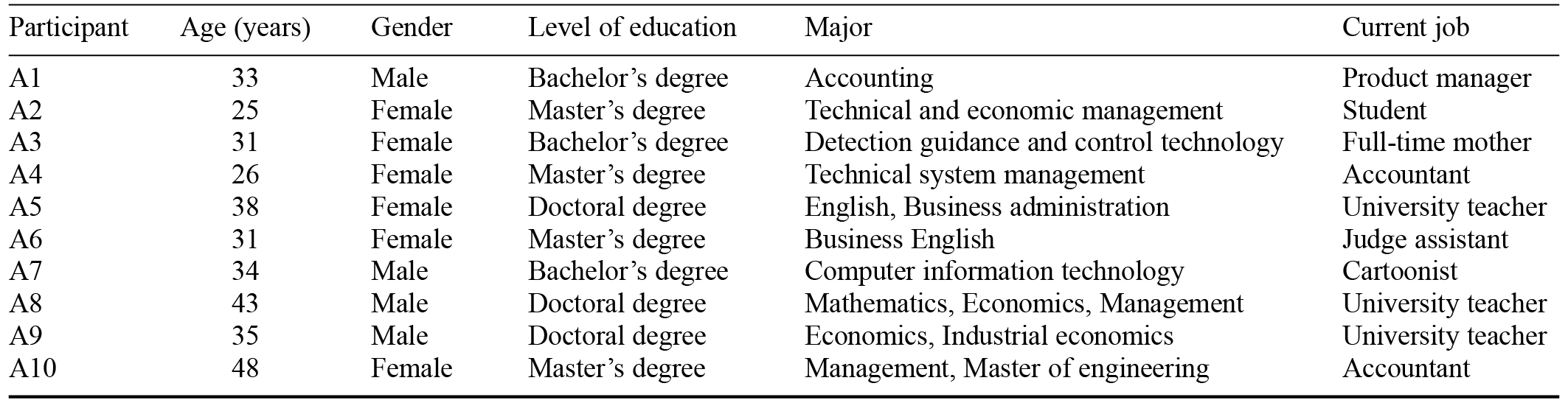

The data were then analyzed after all information to identity the individual had been removed. The demographic characteristics of the interviewees are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Interviewees With No Systematic Music Education

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of Interviewees With Systematic Music Education

Results

Good Advertising Function

The likability of advertising music was found to be related to whether the participants perceived that the music had good advertising functions. One respondent said, “When judging whether I like advertising music, I pay more attention to the role of music in the advertisement” (B7, male, 23 years, student).

The participants identified a number of aspects that they liked in the music used in advertising. First, many interviewees said that the music should fit the advertisement. There are many aspects of fit: (1) Fit with the advertisement picture, for example, when analyzing an advertisement for of Pampers pull-up diapers, one respondent (B10, female, 47 years, elementary school music teacher) said, “The music in the advertisement is quite relaxed and lively, which is suitable for the feeling of children crawling in the picture”; (2) Fit with the product positioning; (3) Fit with the target consumers, for example, “I think good advertising music should first match the positioning of the product and some habits and hobbies of target consumers” (A5, female, 38 years, university teacher); and (4) Fit with the brand, for example, “I feel that this advertising song particularly fits the image of u.loveit [milk tea brand]” (B2, female, 20 years, student).

When music and advertisement are not a good fit, even if the consumers like the music itself, they may not like the advertisement. For example, “The song is good, but it does not match the advertising picture or advertising content. What I mean is that the song is not well-connected with the advertising content, not that the song is bad” (B7, male, 23 years, student). Another interviewee had similar thoughts:

|

The second aspect was whether advertising music caught consumers’ attention. One interviewee commented, “Advertising music can catch me and attract my attention as soon as it is played, and then I will pause and listen to it” (B2, female, 20 years old, student).

The third aspect was whether the advertising music helped consumers remember the advertising content. For example, “If there are lyrics in advertising music, it is best to be catchy, so people listening to it will think of the advertising content” (A7, male, 34 years, cartoonist).

Acceptable Artistic Quality

Although advertising music plays a commercial role, the participants were not indifferent to the artistry of the music. On the contrary, they paid attention to the melody, lyrics, and even arrangement.

| |

I like the advertising music in the BBK cell phone advertisement, but I cannot remember the specific name of the song. When listening to this song, I feel quite comfortable, that is, happy. Because it has a beautiful melody, it sounds very comfortable. (B6, male, 20 years, student) |

Although one reason that participants preferred advertising music was a beautiful melody, this does not mean that music with this feature is perfect for the advertisement. Combined with the above-mentioned concept of fit, the melody was more likely to play its role if the participants perceived that it was a good fit to the advertised product. Perception of poor fit caused consumers to dislike the music and even to feel antipathy toward the product, and also toward the advertisement. Two participants both made comments to this effect (B7, male, 23 years, student; A1 male, 33 years, product manager).

In addition, lyrics that participants found impressive attracted their attention (A2, female, 25 years old, student) and helped them enjoy the advertising music: “I think the lyrics of advertising music should be written to impress customers” (B10, female, 47 years, elementary school music teacher).

If participants felt the advertising music had a harmonious arrangement and excellent lyrics, melody, and singing, their enjoyment increased.

|

Attractive Characteristics

The characteristics of advertising music affected its likability, such as whether it was perceived as “interesting” (A9, male, 35 years old, university teacher), “positive” (B8, male, 24 years old, performer), distinctive, and easy to remember. In addition, advertising music that was easy to remember often impressed the participants.

|

Other interviewees agreed: “I think this song [We Will Rock You by Queen, in an advertisement for a Canon camera] is suitable for young people. It has strong rhythms that are easy to remember” (A6, female, 31 years, judge assistant). “The lyrics can make you remember and stay fresh in your memory so that you will have a better impression of this advertisement song” (B6, male, 20 years, student).

These statements show that the characteristics of advertising music that consumers found distinctive and recognizable not only made them like the music but also caused them to associate the advertised brand with the music.

| |

Intel’s advertising music was excellent in my opinion. I think that if the advertising music is highly recognizable to let people see the brand, and they then think of or hear the music and associate it with the brand, it will be very successful. (A1, male, 33 years, product manager) |

Another respondent agreed: “My favorite advertising music has one thing in common: it is all very distinctive” (B10, female, 47 years, elementary school music teacher).

Storytelling was another likable feature in participants’ eyes. For instance, one participant said, “I like this advertising music because I think it’s kind of like telling a story, it’s kind of like turning a book, page by page; it makes you want to see what the next page is going to say” (A9, male, 35 years, university teacher). A similar comment was made by another participant (A10, female, 48 years, accountant).

Ability to Evoke Positive Affect and Feelings

Respondents formed a good impression when the advertising music aroused positive emotions and feelings, such as evoking beautiful memories, resonating with the music, having an immersive feeling, or feeling happy and comfortable. Two respondents spoke about their memories in relation to their favorite advertising music: “I generally like such music in advertisements, as it can give surprises or stimulate common memories. I like McDonald’s songs very much. It reminds me of my sophomore year when I worked part-time at McDonald’s” (A9, male, 35 years, university teacher). Another participant said:

|

Two interviewees mentioned that the advertisement music stirred feelings and caused them to resonate with it, which means empathy is of significance: “If I sum up the characteristics of good advertisement music, I think the most important point is that there is a kind of empathy. It has to resonate, and the melodies should make us want to hear more” (A9, male, 35 years old, university teacher). “One advertising song I like is for Kangmei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. I think I am driven by the music and can experience its mood” (B9, male, 24 years, song and dance troupe actor).

Many participants mentioned immersion:

|

It should not be overlooked that respondents often mentioned they were happy and comfortable rather than sad or depressed when they heard the advertising music they liked: “Among the advertisements I have seen before, I prefer Rhythm of the Rain in the advertisement for Doublemint. The rhythm is very brisk, and with the video, the advertisement gives a relatively fresh feeling. It made me feel good” (A5, female, 38 years old, university teacher). “I like the BBK cell phone’s advertisement music. Song Hye Kyo acted in it. I think that music is cheerful and clear. Yes, it just sounds comfortable” (B4, female, 21 years, student).

Discussion

In this study we identified four themes of advertising music that consumers like, which can help guide the selection of such music. Our work builds on previous studies related to this topic (e.g., Craton & Lantos, 2011; Lantos & Craton, 2012; Raja et al., 2018). For example, Craton and Lantos (2011) summarized the components of and factors influencing AAM, Raja et al. (2018) examined how to measure AAM, and we sought to determine the characteristics of music that may induce a positive AAM. We used a qualitative method and thematic analysis, which are not wedded to any pre-existing theoretical frameworks (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Our findings increase understanding of the inner world of consumers and their views on advertising music.

Theoretical Implications

Among the four themes of advertising music that we identified, the first and second themes indicate that advertising music liked by consumers should have both commercial function and artistic quality. In the first theme, our findings about good advertising function echo those of some previous studies regarding the positive effects of music–message congruency and music–brand congruency on consumers’ reactions. When the background music of an advertisement evokes message-congruent (vs. message-incongruent) thoughts, increasing the audience’s attention to the music can enhance message reception (Kellaris et al., 1993). In high-cognition advertisements, congruent music (i.e., music that consumers perceive as being a good fit to the brand) results in a more positive attitude towards the advertisement and the brand (Lavack et al., 2008) than does either incongruent music or no music. Our findings emphasize that advertising music should fit the product and the target group of consumers. This is consistent with the study by Herget et al. (2020), which systematically determined musical fit in an audiovisual advertisement. To do this, the authors evaluated the level of musical fit by evaluating whether the music was a good fit for narration, product, and target group, and found that product and target group were important to evaluate the degree of fit of a piece of advertising music. Lalwani et al. (2009) also emphasized the importance of the fit between the music and the pictures used in the advertisement.

The capacity of the advertisement to attract viewers’ or listeners’ attention has long been regarded as one of the functions of use of music in advertisements (Craton & Lantos, 2011; Hecker, 1984; Lantos & Craton, 2012). Hecker (1984) pointed out that music often helps draw attention to both the advertisement itself and the product being advertised. According to Craton and Lantos (2011), the level and persistence of attention to advertising music is a component of consumers’ attitude toward the music, and attracting attention is the corresponding advertising objective. In line with this, our findings indicate that consumers preferred advertising music that caught their attention.

Enhancing consumers’ memory of advertising content is the corresponding objective of depth of processing of music, which is one component of AAM (Craton & Lantos, 2011). We found that consumers who like advertising music tend to remember the advertising content, which supports the results of Raja et al. (2018).

The second theme emphasizes that consumers like advertising music with high artistic quality, including beautiful melody, impressive lyrics, harmonious arrangements, and good singing. Negative cognition and affect arising from any AAM components can be caused by an unfavorable combination of an advertisement’s musical structural characteristics (Lantos & Craton, 2012). In line with our findings, Lantos and Craton (2012) emphasized the importance of the structural characteristics of melody and texture. In addition, Allan (2006) found that song vocals were more effective stimuli of advertisement effects than were instrumental songs or those with no popular music. They further showed that lyrics (either original or altered) are important, which aligns with our finding that impressive lyrics can lead consumers to like advertising music. The “singing well” component mentioned by our participants has been reported on in few past studies, making this a novel contribution to the literature.

In the third theme, our participants noted interesting, positive, and storytelling as attractive characteristics of advertising music, which are relatively new findings in the advertising music field. The remaining characteristics our participants suggested, comprising easy to remember and distinctive, have been supported in previous studies. Raja et al. (2018) showed that music memorability was an important factor, and our findings are consistent with this. Further, in line with Lantos and Craton (2012), our findings show that consumers liked advertising music that they thought was distinctive.

In the fourth theme, consumers liked advertising music that made them feel immersive and comfortable. This is a relatively new finding. Emotional memories activated by music are an affective component of AAM (Lantos & Craton, 2012), which aligns with our finding that advertising music is liked if it evokes good memories. In Hecker’s (1984) study of music for advertising effect, he pointed out that empathy is often achievable at least partially through music. This shows that music can make consumers feel empathetic, and our research further demonstrates the positive effect of empathy on attitude toward advertising music. Our findings are also similar to those of Raja et al. (2018), showing the importance of pleasure induced by listening to advertising music.

Practical Implications

This research has rich practical significance. First, the study findings show that advertising music plays an important role that needs to be accounted for in marketing. Because music is not a trivial part of an advertisement, consumers will also care about its artistic expression. Further, the findings can help advertisers to gain understanding of the inner world of consumers and find out what they like. The findings of this study can provide advertisers with detailed guidance when choosing, making, or improving advertising music. This will help advertisers to make music that consumers like in their advertisement, thus enhancing the possibility of generating positive consumer responses, and further contributing to achieving good advertising effectiveness.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has some limitations. First, the participants comprised a small group of Chinese consumers. Owing to cultural differences, the advertising music that consumers like may differ in other countries and regions. Because listeners tend to “exhibit biases favoring the music of their native culture” (Swaminathan & Schellenberg, 2015, p. 190), our conclusions may not be generalizable outside China. Future research could focus on advertising music liked by consumers in other countries and regions. Second, our data were qualitative in nature. This allowed us to summarize the common characteristics of consumers’ favorite music and identify new factors that affect consumers’ attitudes toward music in advertisements. However, we cannot distinguish which characteristics were the most important and had the greatest impact on the final AAM. The next step could be to add quantitative research based on these findings and compare effects of the characteristics and influencing factors identified in this study on AAM and consumer responses. Finally, future research could be conducted to examine whether characteristics of consumers’ favorite advertising music differ according to the medium through which the music is heard (e.g., social media, radio, television).

References

Allan, D. (2006). Effects of popular music in advertising on attention and memory. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), 434–444.

https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849906060491

Belk, R. W. (2017). Qualitative research in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 36–47.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1201025

Bierley, C., McSweeney, F. K., & Vannieuwkerk, R. (1985). Classical conditioning of preferences for stimuli. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 316–323.

https://doi.org/10.1086/208518

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chou, H.-Y., & Lien, N.-H. (2010). Advertising effects of songs’ nostalgia and lyrics’ relevance. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 22(3), 314–329.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851011062278

Chou, H.-Y., & Singhal, D. (2017). Nostalgia advertising and young Indian consumers: The power of old songs. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(3), 136–145.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2016.11.004

Craton, L. G., & Lantos, G. P. (2011). Attitude toward the advertising music: An overlooked potential pitfall in commercials. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(6), 396–411.

https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761111165912

Craton, L. G., Lantos, G. P., & Leventhal, R. C. (2017). Results may vary: Overcoming variability in consumer response to advertising music. Psychology & Marketing, 34(1), 19–39.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20971

De Pelsmacker, P. D. (2021). What is wrong with advertising research and how can we fix it? International Journal of Advertising, 40, 835–848.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1827895

Finnäs, L. (1989). How can musical preferences be modified? A research review. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 102, 1–58. https://bit.ly/3nz9Vh0

Galan, J.-P. (2009). Music and responses to advertising: The effects of musical characteristics, likeability and congruency. Recherche et Applications En Marketing (English Edition), 24(4), 3–22.

https://doi.org/10.1177/205157070902400401

Gorn, G. J. (1982). The effects of music in advertising on choice behavior: A classical conditioning approach. Journal of Marketing, 46(1), 94–101.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1251163

Hecker, S. (1984). Music for advertising effect. Psychology & Marketing, 1(3–4), 3–8.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220010303

Herget, A.-K., Breves, P., & Schramm, H. (2020). The influence of different levels of musical fit on the efficiency of audio-visual advertising. Musicae Scientiae. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864920904095

Herrington, J. D. (1996). Effects of music in service environments: A field study. Journal of Services Marketing, 10(2), 26–41.

https://doi.org/10.1108/08876049610114249

Hussain, S., Melewar, T. C., Priporas, C. V., & Foroudi, P. (2020). Examining the effects of advertising credibility on brand credibility, corporate credibility and corporate image: A qualitative approach. Qualitative Market Research, 23(4), 549–573.

https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-12-2017-0175

Kellaris, J. J., & Cox, A. D. (1989). The effects of background music in advertising: A reassessment. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(1), 113–118.

https://doi.org/10.1086/209199

Kellaris, J. J., Cox, A. D., & Cox, D. (1993). The effect of background music on ad processing: A contingency explanation. Journal of Marketing, 57(4), 114–125.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1252223

Kupfer, P. (2017). Classical music in television commercials: A social-psychological perspective. Music and the Moving Image, 10(1), 23–53.

https://doi.org/10.5406/musimoviimag.10.1.0023

Lalwani, A. K., Lwin, M. O., & Ling, P. B. (2009). Does audiovisual congruency in advertisements increase persuasion? The role of cultural music and products. Journal of Global Marketing, 22(2), 139–153.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08911760902765973

Lantos, G. P., & Craton, L. G. (2012). A model of consumer response to advertising music. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(1), 22–42.

https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211193028

Lavack, A. M., Thakor, M. V., & Bottausci, I. (2008). Music-brand congruency in high-and low-cognition radio advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 27(4), 549–568.

https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048708080141

Middleton, K., Turnbull, S., & de Oliveira, M. J. (2020). Female role portrayals in Brazilian advertising: Are outdated cultural stereotypes preventing change? International Journal of Advertising, 39(5), 679–698.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1658428

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1997). In-store music affects product choice. Nature, 390(6656), Article 132.

https://doi.org/10.1038/36484

North, A. C., MacKenzie, L. C., Law, R. M., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2004). The effects of musical and voice “fit” on responses to advertisements. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(8), 1675–1708.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02793.x

Park, H. H., Park, J. K., & Jeon, J. O. (2014). Attributes of background music and consumers’ responses to TV commercials: The moderating effect of consumer involvement. International Journal of Advertising, 33(4), 767–784.

https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-33-4-767-784

Peretz, I., Gaudreau, D., & Bonnel, A.-M. (1998). Exposure effects on music preference and recognition. Memory & Cognition, 26(5), 884–902.

https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03201171

Pitt, L. F., & Abratt, R. (1988). Music in advertisements for unmentionable products—A classical conditioning experiment. International Journal of Advertising, 7(2), 130–137.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1988.11107051

Priporas, C.-V., Stylos, N., & Fotiadis, A. K. (2017). Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 374–381.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.058

Raja, M. W., Anand, S., & Kumar, I. (2018). Multi-item scale construction to measure consumers’ attitude toward advertising music. Journal of Marketing Communications, 26(3), 314–327.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2018.1471615

Schäfer, T., & Sedlmeier, P. (2010). What makes us like music? Determinants of music preference. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4(4), 223–234.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018374

Stewart, K., & Koh, H. E. (2017). Hooked on a feeling: The effect of music tempo on attitudes and the mediating role of consumers’ affective responses. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(6), 550–564.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1665

Swaminathan, S., & Schellenberg, E. G. (2015). Current emotion research in music psychology. Emotion Review, 7(2), 189–197.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914558282

Tom, G. (1995). Classical conditioning of unattended stimuli. Psychology & Marketing, 12(1), 79–87.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220120106

Vermeulen, I., & Beukeboom, C. J. (2016). Effects of music in advertising: Three experiments replicating single-exposure musical conditioning of consumer choice (Gorn 1982) in an individual setting. Journal of Advertising, 45(1), 53–61.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2015.1088809

Appendix

Recorded Video Advertisements Used as Research Stimuli

Allan, D. (2006). Effects of popular music in advertising on attention and memory. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), 434–444.

https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849906060491

Belk, R. W. (2017). Qualitative research in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 36–47.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1201025

Bierley, C., McSweeney, F. K., & Vannieuwkerk, R. (1985). Classical conditioning of preferences for stimuli. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 316–323.

https://doi.org/10.1086/208518

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chou, H.-Y., & Lien, N.-H. (2010). Advertising effects of songs’ nostalgia and lyrics’ relevance. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 22(3), 314–329.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851011062278

Chou, H.-Y., & Singhal, D. (2017). Nostalgia advertising and young Indian consumers: The power of old songs. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(3), 136–145.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2016.11.004

Craton, L. G., & Lantos, G. P. (2011). Attitude toward the advertising music: An overlooked potential pitfall in commercials. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(6), 396–411.

https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761111165912

Craton, L. G., Lantos, G. P., & Leventhal, R. C. (2017). Results may vary: Overcoming variability in consumer response to advertising music. Psychology & Marketing, 34(1), 19–39.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20971

De Pelsmacker, P. D. (2021). What is wrong with advertising research and how can we fix it? International Journal of Advertising, 40, 835–848.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1827895

Finnäs, L. (1989). How can musical preferences be modified? A research review. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 102, 1–58. https://bit.ly/3nz9Vh0

Galan, J.-P. (2009). Music and responses to advertising: The effects of musical characteristics, likeability and congruency. Recherche et Applications En Marketing (English Edition), 24(4), 3–22.

https://doi.org/10.1177/205157070902400401

Gorn, G. J. (1982). The effects of music in advertising on choice behavior: A classical conditioning approach. Journal of Marketing, 46(1), 94–101.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1251163

Hecker, S. (1984). Music for advertising effect. Psychology & Marketing, 1(3–4), 3–8.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220010303

Herget, A.-K., Breves, P., & Schramm, H. (2020). The influence of different levels of musical fit on the efficiency of audio-visual advertising. Musicae Scientiae. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864920904095

Herrington, J. D. (1996). Effects of music in service environments: A field study. Journal of Services Marketing, 10(2), 26–41.

https://doi.org/10.1108/08876049610114249

Hussain, S., Melewar, T. C., Priporas, C. V., & Foroudi, P. (2020). Examining the effects of advertising credibility on brand credibility, corporate credibility and corporate image: A qualitative approach. Qualitative Market Research, 23(4), 549–573.

https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-12-2017-0175

Kellaris, J. J., & Cox, A. D. (1989). The effects of background music in advertising: A reassessment. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(1), 113–118.

https://doi.org/10.1086/209199

Kellaris, J. J., Cox, A. D., & Cox, D. (1993). The effect of background music on ad processing: A contingency explanation. Journal of Marketing, 57(4), 114–125.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1252223

Kupfer, P. (2017). Classical music in television commercials: A social-psychological perspective. Music and the Moving Image, 10(1), 23–53.

https://doi.org/10.5406/musimoviimag.10.1.0023

Lalwani, A. K., Lwin, M. O., & Ling, P. B. (2009). Does audiovisual congruency in advertisements increase persuasion? The role of cultural music and products. Journal of Global Marketing, 22(2), 139–153.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08911760902765973

Lantos, G. P., & Craton, L. G. (2012). A model of consumer response to advertising music. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(1), 22–42.

https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761211193028

Lavack, A. M., Thakor, M. V., & Bottausci, I. (2008). Music-brand congruency in high-and low-cognition radio advertising. International Journal of Advertising, 27(4), 549–568.

https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048708080141

Middleton, K., Turnbull, S., & de Oliveira, M. J. (2020). Female role portrayals in Brazilian advertising: Are outdated cultural stereotypes preventing change? International Journal of Advertising, 39(5), 679–698.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1658428

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1997). In-store music affects product choice. Nature, 390(6656), Article 132.

https://doi.org/10.1038/36484

North, A. C., MacKenzie, L. C., Law, R. M., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2004). The effects of musical and voice “fit” on responses to advertisements. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(8), 1675–1708.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02793.x

Park, H. H., Park, J. K., & Jeon, J. O. (2014). Attributes of background music and consumers’ responses to TV commercials: The moderating effect of consumer involvement. International Journal of Advertising, 33(4), 767–784.

https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-33-4-767-784

Peretz, I., Gaudreau, D., & Bonnel, A.-M. (1998). Exposure effects on music preference and recognition. Memory & Cognition, 26(5), 884–902.

https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03201171

Pitt, L. F., & Abratt, R. (1988). Music in advertisements for unmentionable products—A classical conditioning experiment. International Journal of Advertising, 7(2), 130–137.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1988.11107051

Priporas, C.-V., Stylos, N., & Fotiadis, A. K. (2017). Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing. Computers in Human Behavior, 77, 374–381.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.058

Raja, M. W., Anand, S., & Kumar, I. (2018). Multi-item scale construction to measure consumers’ attitude toward advertising music. Journal of Marketing Communications, 26(3), 314–327.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2018.1471615

Schäfer, T., & Sedlmeier, P. (2010). What makes us like music? Determinants of music preference. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4(4), 223–234.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018374

Stewart, K., & Koh, H. E. (2017). Hooked on a feeling: The effect of music tempo on attitudes and the mediating role of consumers’ affective responses. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(6), 550–564.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1665

Swaminathan, S., & Schellenberg, E. G. (2015). Current emotion research in music psychology. Emotion Review, 7(2), 189–197.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914558282

Tom, G. (1995). Classical conditioning of unattended stimuli. Psychology & Marketing, 12(1), 79–87.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220120106

Vermeulen, I., & Beukeboom, C. J. (2016). Effects of music in advertising: Three experiments replicating single-exposure musical conditioning of consumer choice (Gorn 1982) in an individual setting. Journal of Advertising, 45(1), 53–61.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2015.1088809

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Interviewees With No Systematic Music Education

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of Interviewees With Systematic Music Education

Yongzhong Yang, Business School, Sichuan University, No. 24, South Section 1, First Ring Road, Wuhou District, Chengdu 610065, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected]