Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude and relationships with subjective well-being

Main Article Content

It has been well documented that psychology has been more interested in studying human vice than virtue (e.g., Myers & Diener, 1995). Gratitude appears to be one of the neglected virtues in psychology. Although linguistic equivalents for gratitude reside in virtually every language and major religions have emphasized the importance of grateful expression (Emmons & Crumpler, 2000), very little attention has been paid to gratitude in the social sciences.

However, there are several reasons why gratitude may be important to investigate. Research indicates that gratitude is important to people (Gallup, 1998), and "grateful" appears to be a highly valued trait. In a recent study of over 800 descriptive trait words, "grateful" was rated in the top four percent in terms of likeability (Dumas, Johnson, & Lynch, 2002). Conversely, "ungrateful" was rated as one of the most negative traits (in the bottom 1.7%). Also, gratitude may be a strength important to the good life. Although this is one of the primary questions of this article, there are some conceptual analyses and empirical indications that suggest ways in which gratitude might be important to emotional well-being (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002; Watkins, in press).

Emotion may be studied as an immediate feeling state, as a more enduring climate of mood, or as an affective trait (Rosenberg, 1998). The term affective trait refers to how likely a given individual is to experience a particular emotion. Thus, the affective trait of gratitude may be thought of as a predisposition to experience gratitude. A grateful person may not experience grateful feelings at any given moment, but he/she will be more likely to experience gratitude in particular situations. Thus, grateful individuals have a lower threshold for gratitude. This analysis implies that a science of gratitude should embark on studies of both the state and trait of gratitude. In this article we describe the development of a measure of trait gratitude, as well as relationships between the grateful disposition and grateful feelings. Grateful affect may be defined as a feeling of thankful appreciation for favors received (Guralnik, 1971, p. 327), and trait gratitude would be the predisposition to experience this state.

A successful measure of dispositional gratitude should be developed from a clear theory of what grateful individuals are like. In creating our gratitude measure, we felt that grateful persons would have four characteristics. First, we reasoned that grateful individuals would not feel deprived in life. Stated positively, grateful individuals should have a sense of abundance. Second, we reasoned that grateful individuals would be appreciative of the contribution of others to their well-being. Theories of gratitude have emphasized the importance of attributing the source of benefits to others (e.g., Weiner, 1985), and generally speaking experimental research has supported this hypothesis (for a review see McCullough, Kilpatrick, Emmons, & Larson, 2001). Third, we felt that grateful persons would be characterized by the tendency to appreciate simple pleasures. Simple pleasures refers to those pleasures in life that are readily available to most people. Individuals who appreciate simple pleasures should be more prone to experience grateful feelings because they will experience subjective benefits more frequently in their daily lives. Finally, we expected that grateful individuals should acknowledge the importance of experiencing and expressing gratitude. In creating our measure of trait gratitude we attempted to create items that tapped these four characteristics, and called our measure the Gratitude,Resentment, and Appreciation Test (GRAT).

Implicit in our understanding of grateful persons is that experiencing and expressing gratitude should enhance one's subjective well-being (SWB). In his attempt to understand the function of praise, C. S. Lewis observed,

I think we delight to praise what we enjoy because the praise not merely expresses but completes the enjoyment; it is its appointed consummation. It is not out of compliment that lovers keep on telling one another how beautiful they are; the delight is incomplete until it is expressed. (Lewis, 1958, p. 95)

Thus, Lewis argued that praise enhances enjoyment of benefits, and if praise is simply the verbal expression of gratitude, experiences of gratitude should complete the enjoyment of benefits in life. Following this line of reasoning, experiences and expressions of gratitude should enhance SWB, and thus, those who are disposed to gratitude should also demonstrate more happiness. A second purpose of the studies described here was to evaluate the relationship between gratitude and happiness.

In this article we report four studies that describe the development of the GRAT and also illuminate relationships between trait gratitude, grateful feelings, and happiness. In Study 1 we describe our initial development of the GRAT. In Study 2 we compared the GRAT with a number of different measures in several populations in an attempt to demonstrate the construct validity of this measure. In Studies 3 and 4 we report two experiments that manipulated gratitude to investigate causative relationships with affect. In addition, we investigated how the disposition of gratitude might interact with these manipulations.

Study 1

The purpose of this study was to develop a reliable measure of dispositional gratitude following our theory of grateful persons as described earlier.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Our initial population consisted of 237 students. All participants were enrolled in an undergraduate psychology course and received partial course credit for their involvement. Participants were administered the preliminary item set of the GRAT in several group settings.

Preliminary Form Development

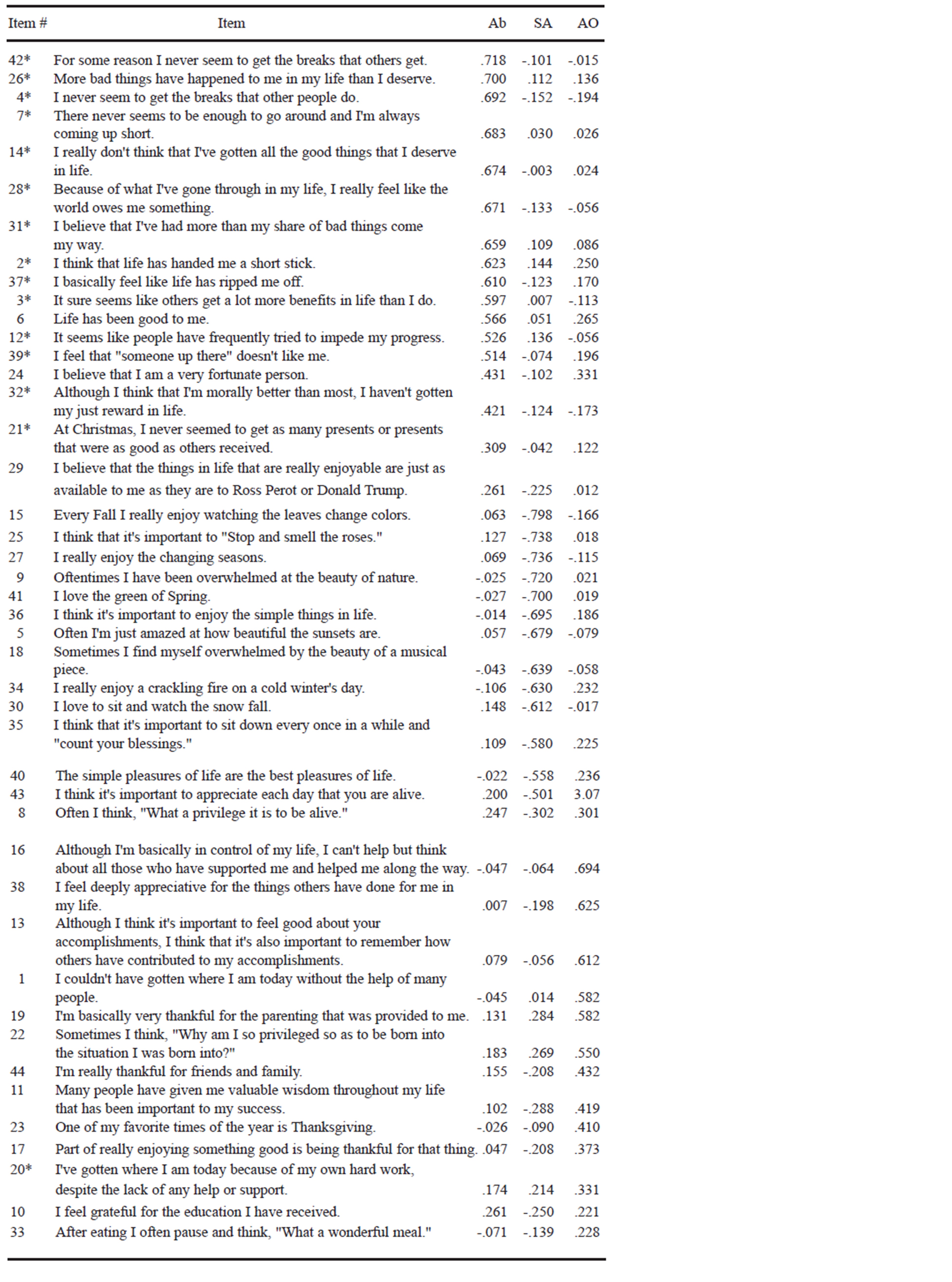

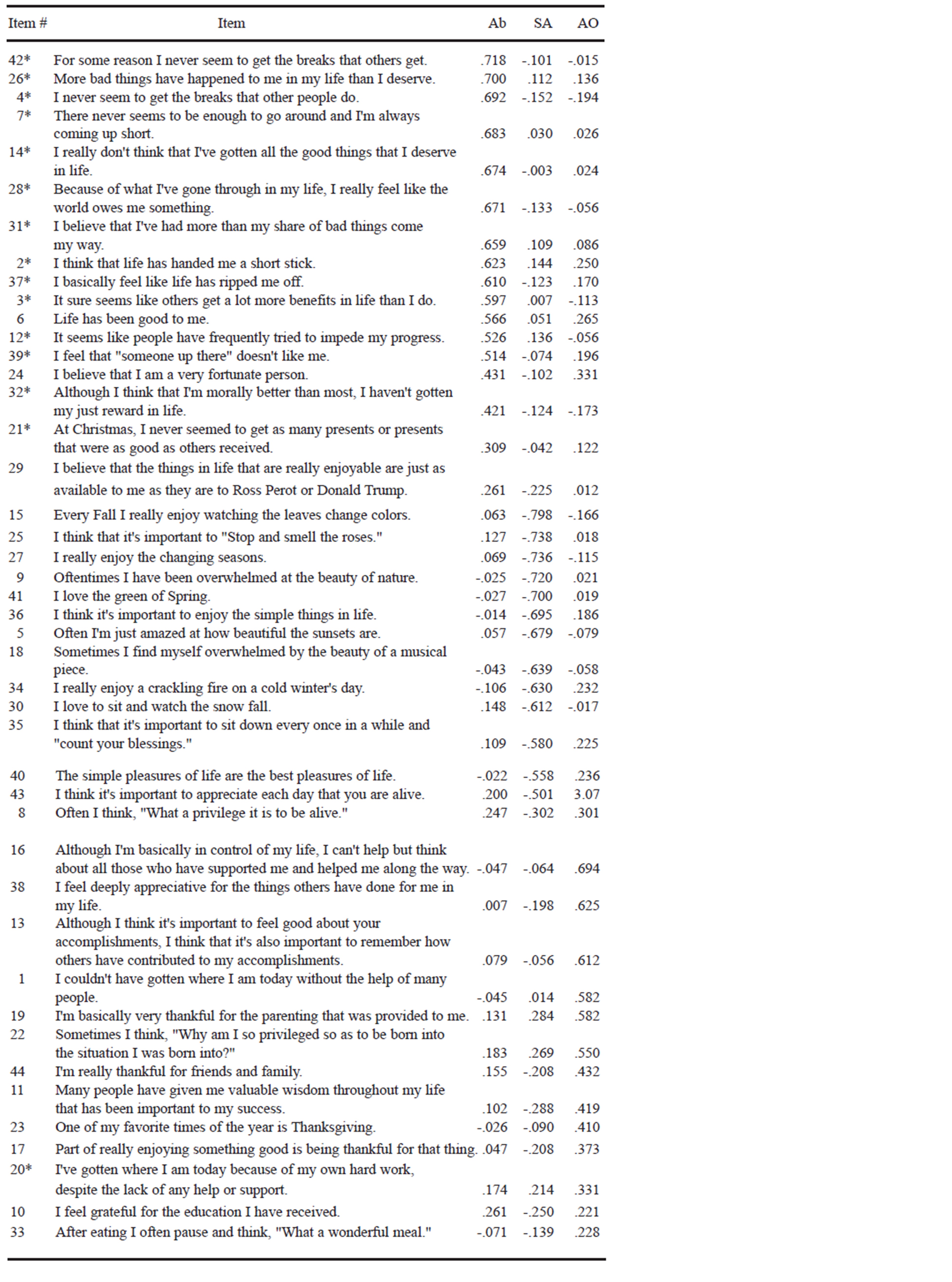

We initially created 53 questions that we felt tapped the four domains of a sense of abundance, simple appreciation, appreciation for others, and importance of gratitude expression. Nine items were eliminated due to poor item-total correlations. The final 44 items are shown on Table 1. Participants were instructed to read each item and to indicate their agreement/disagreement on a five point Likert-type scale (1= I strongly disagree, 5 = I strongly agree with the statement). Of the final 44 items, 14 are reverse scored. These items are indicated on Table 1.

* Indicates item is reverse scored. Ab=Sense of Abundance, SA=Simple Appreciation, AO=Appreciation for Others.

Results

We first conducted corrected item-to-total correlations to determine the items for the final measure. All items with less than .20 correlations were eliminated. This left the final 44 items shown in Table 1. Mean corrected item-to-total correlation was .44 (SD =.11). The internal consistency for the final 44 item measure was good (coefficient alpha = .92).

We followed this analysis by conducting a principle components factor analysis (with oblimin rotation) to evaluate the four proposed characteristics of gratitude. Three factors had eigenvalues above 2.00. We then extracted three factors. Factor loading for the items are shown on Table 1. Generally speaking, this factor structure fitted our proposed characteristics of gratitude with few exceptions.

However, items relating to the appreciation of others and to the importance of expressing gratitude clustered in one factor. Following our convention, we entitled factor 1 "Sense of Abundance" (Ab), factor 2 "Simple Appreciation" (SA), and factor 3 "Appreciation of Others" (AO). Table 1 indicates the factors to which each item belongs. The last two items listed did not clearly fall into any of the factors (i.e., relatively equivalent factor loadings on all three factors). Each factor showed adequate internal consistency as revealed by coefficient alpha (Ab = .88, SA = .90, AO = .76). Mean GRAT scores for this population were 176.61 (SD = 17.33), and mean factor scores were: Ab = 66.48 (SD = 8.83), SA = 58.64 (SD = 7.48), and AO = 43.63 (SD = 5.20). Across six years, six different student populations, and 1,187 participants, total GRAT scores averaged 176.62 (SD = 22.02), and mean factors scores were: Ab = 67.61 (SD =11.68), SA = 57.40 (SD = 8.59), and AO = 43.88 (SD = 6.28).

Discussion

The initial development of the GRAT appeared to be successful. The measure showed good internal consistency and factorial validity. Factor analysis supported the proposed structure of grateful persons, with the exception that items related to the importance of expressing gratitude clustered in one factor with items related to the appreciation of others. In retrospect, this makes some sense because the expression of gratitude is typically a social expression. Individuals who are appreciative of the contribution of others are also likely to express gratitude to their benefactors and believe that expressing thanks to their benefactors is important. This study showed that the GRAT is a reliable instrument in terms of internal consistency and factorial validity.

Study 2

The principal aim of Study 2 was to examine criterion-related validity for the GRAT using several different populations. At the time of this study there were no direct measures of trait gratitude and so we investigated the validity of the GRAT by comparing it with a number of measures we felt would be indirectly related to dispositional gratitude. In a nutshell, we predicted that trait gratitude would be positively related to positive affects and SWB, and negatively related to unpleasant states. Following from our notion that gratitude functions to enhance positive affect, we predicted that the GRAT would be more strongly related to positive affectivity than to negative affectivity. Of the negative affects, we predicted that gratitude would show the strongest inverse relationship with depression because those vulnerable to depression should be more likely to feel deprived, which should degrade their sense of gratitude. We felt that gratitudewould also be inversely related to resentment. We reasoned that if a person is resentful about his or her past s/he is not likely to experience pervasive gratitude.

We also conducted several exploratory investigations. First, we were interested in the relationship between religiosity and gratitude. We reasoned that because many religious individuals believe that the first cause of all benefits resides in a good giver (God), they would be more prone to experience gratitude, because all benefits are experienced as gifts from God (cf. McCullough et al., 2002). This prediction would seem to hold for intrinsically religious individuals (i.e., those who practice religion for a relationship with the divine), but not for extrinsically religious individuals (those who practice religion for secondary gain).

Finally, we felt it important to evaluate the relationship between gratitude and locus of control. It could be that gratitude fosters an external locus of control because grateful responses are experienced in the context of an external attribution for a benefit. However, grateful individuals could have an internal locus of control in that they accurately recognize their own contribution to good things in life, but are more likely than less grateful individuals to acknowledge the contribution of others as well.

Method

In three different groups of participants we administered various questionnaires along with the GRAT to evaluate the proposed relationships outlined above. In each case the questionnaires were administered in a group format in undergraduate psychology courses. Students received partial course credit for their participation.

Materials

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is one of the most commonly used measures of SWB (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985), and focuses on the cognitive judgment aspect of SWB (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999). The Fordyce Happiness Scales (HS) provide a more affective index of a person's overall happiness (Fordyce, 1988). Although the four scales on this measure are single items scales, this measure appears to have good validity and is frequently used in happiness research. The Positive and Negative Affectivity Scales (PANAS) is one of the most well developed measures of positive and negative affectivity (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). This measure is based on the theory that positive and negative emotional states are not simply bipolar opposites, but are largely orthogonal axes in affective space. In these populations we administered these scales with the instruction to "Indicate to what extent you generally feel that way." The Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ) asks participantsto indicate whether or not certain stressful events have occurred to them in the last six months (Brugha & Cragg, 1990). If the GRATis indeed a trait measure of gratitude, we felt that gratitude would not be unduly affected by recent stressful experiences. As we argued earlier, comparisons between dispositional gratitude and locus of control could be very interesting. We used the Belief in Personal Control Scale (BPCS; Berrenberg, 1987) because not only does it assess general internal versus external locus of control, it also contains scales for an exaggerated sense of control, and also measures how much personal control an individual believes they have through the assistance of a divine being. The factor measuring exaggerated sense of control assesses an individual's unrealistic belief in his or her control of events. The Religious Orientation Scale (ROS) taps two orthogonal dimensions of religious orientation (Allport & Ross, 1967). Intrinsically religious persons are said to engage in religious practices for their own sake, whereas extrinsically religious persons participate in religion for other gains outside of religion (e.g., material gains and social status). We predicted that gratitude would be positively related to intrinsic religiosity, but would show no relationship with extrinsic religiosity. The Semantic Differential Feeling and Mood States (SDFMS) scale contains 35 semantic differential items with bipolar emotional states (Lorr & Wunderlich, 1988), which are divided into five subscales. We used this measure to assess the immediate affective states of our respondents. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is one of the most commonly used measures of depression, and has extensive reliability and validity data supporting its use (e.g., Beck, 1972). The Aggression Questionnaire (AQ) is one of the most widely used instruments assessing various aspects of anger, and has good psychometric properties (Buss & Perry, 1992). It contains four subscales that tap physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility (or resentment). We predicted that gratitude would be most strongly associated with resentment. The Selfism Scale (NS) is designed to tap subclinical narcissism, and it appears to have adequate psychometric properties (Phares & Erskine, 1984). We reasoned that narcissistic individuals would be less likely to be grateful because research has shown that if people feel they are entitled to benefits, they are less likely to feel grateful (for reviews see McCullough et al., 2001; Watkins, 2001). Thus, we predicted an inverse correlation between the NS and the GRAT.

Populations

Population 1 consisted of 57 students. They were administered the GRAT with the following measures: SWLS, PANAS, SDFMS, LEQ, BPCS, ROS, BDI, AQ, and the NS. Population 2 consisted of 66 individuals who completed the GRAT along with the following measures: SWLS, HS, PANAS, and the BDI. With this population we administered the GRAT twice, at the beginning and end of the series of questionnaires. This afforded us an opportunity to evaluate within-session temporal stability of the GRAT. In Population 3 we administered the GRAT, BDI, and SWLS to 154 participants.

Results and Discussion

A summary of our results is presented in Table 2. In general, results supported our predictions. The two administrations of the GRAT were highly correlated (r = .94), providing some support for the temporal stability of the GRAT.

Correlations with SWB and Positive Affect Variables

The GRAT showed strong relationships with various measures of positive affect. Correlations with the SWLS ranged between .49 and .62 in the three populations. Other SWB variables showed similar associations with the GRAT. In general, results showed that dispositional gratitude was more strongly related to positive affect than to negative affect.

Correlations with Negative Affect and Maladaptive Traits

Of the variables tapping negative states, depression showed the strongest and most reliable inverse associations with gratitude. As predicted, the BDI showed moderate to strong negative correlations with the GRAT. It should be noted that other negative affects (anxiety and irritability) did not show reliable relationships with the GRAT. Does gratitude have a unique relationship with depression among psychological disorders? This issue may be a fruitful avenue for future research.

Interestingly, the number of stressful events in the last six months showed no relationship to the GRAT (r = .04). This did not appear to be due to the insensitivity of the LEQ, as number of recent stressful events was reliably associated with the BDI (r = .30, p < .05). Thus, the GRATdid not appear to be reactive to significant recent stressors. If the GRAT is indeed tapping a trait variable, this would be the expected finding.

Gratitude was also inversely associated with some anger-related variables. In particular, the GRAT showed inverse correlations with physical aggression and resentment (i.e., "Hostility"). Feeling resentful about the past may contravene a grateful attitude in the present. Conversely, it could be that grateful experiences counteract resentment.

As predicted, we also found that gratitude was negatively related to narcissism. Although this relationship was as predicted, we were somewhat surprised at the strength of the association (r = -.49). The investigation of relationships between narcissism, humility, and gratitude, presents promising research possibilities.

Gratitude and Religiosity

We also predicted that intrinsic religiosity would be positively related to gratitude, and our results supported this notion. Additionally, extrinsic religiosity was significantly and negatively associated with gratitude. Thus, it appears that individuals who engage in religious practice as an end in itself tend to be more grateful, but those who engage in a more instrumental religiosity tend to be less grateful. Intrinsic religiosity may enhance gratitude because these individuals see the ultimate source of all benefits in life in a good God. However, some have also suggested that experiences of gratitude may promote belief in God (e.g., see Chesterton, 1908/1986, p. 258. McCullough et al., 2002).

Gratitude and Locus of Control

In a more exploratory analysis we investigated relationships of dispositional gratitude with locus of control. We found that the GRAT was positively correlated with an internal locus of control, but was not related to a maladaptive sense of personal control. At first glance, this appears to be a paradoxical finding, because in order to experience gratitude people must make an external attribution for the benefit. McCullough and colleagues (2002) have suggested that grateful individuals may be willing to attribute benefits to themselves when they, are, in fact, responsible. However, they argue that grateful individuals should be more likely to attribute benefits to many sources. Alternatively, it could be that individuals with an internal locus-of-control do not expect others to provide benefits, and therefore favors from others are more salient and more likely to generate gratitude. Conversely, individuals with an external locus-of-control may expect others to bring them benefits, thus decreasing their experience of gratitude when favors are provided. Research has shown that gratitude is more likely when favors exceed social expectations (Bar-Tal, Bar-Zohar, Greenberg, & Hermon, 1977).

The relationship between the Divine Control scale of the BPCS and the GRAT might be informative to this issue. The positive correlation here (r=.49), suggests that grateful individuals are more likely to feel in control of their destiny through the actions of a divine entity who is interested in their well-being. This implies that one can feel in control of one’s future and well-being through one’s confidence in the goodness of others. If people feel grateful for how others have contributed to their lives in the past, it is likely that they will also feel in control of their destiny because they are confident that others will contribute in a positive way to their well-being in the future. At this point, these ideas are speculative, but future research may illuminate this interesting relationship.

In sum, this study provided evidence of construct validity for the GRAT and also illuminated relationships between gratitude and positive and negative affective states. Results revealed strong relationships between gratitude and various happiness measures. In addition, gratitude was inversely related to several unpleasant states, but appeared to show the strongest negative relationship with depression. Grateful individuals also appeared to be less narcissistic, more intrinsically religious, and tended to have an internal locus of control. Although these results support the theory that gratitude enhances happiness, it is also possible that gratitude is somewhat of an epiphenomenon of happiness. In studies 3 and 4 we conducted experimental studies in an effort to evaluate whether gratitude promotes positive affect.

Study 3

In this study we investigated whether gratitude might enhance mood. In addition, we administered the GRAT, which allowed us to further evaluate the criterion-related validity of the GRAT. Specifically, we asked whether grateful individuals were more likely to experience gratitude and positive affect in the context of a gratitude manipulation.

Method

Participants

One hundred and four students from undergraduate psychology courses at Eastern Washington University participated in this study. Participants received partial course credit for being involved in this study.

Materials

In addition to the GRAT, we also administered the SDFMS, SWLS, and the BDI to provide additional construct validity data on the GRAT. Our primary dependent variable in this study was the PANAS. In this study we used the immediate state version of the PANAS ("Indicate to what extent you feel that way right now at this moment"). We also administered 10 neutral words to which participants supplied 4 semantic differential ratings to each word on a 7-point Likert scale (Kuykendall, Keating, & Wagaman, 1988). This provided us with an indirect measure of SWB. Our previously presented comparisons of gratitude with happiness measures are vulnerable to the criticism of the relationship being created by similar desirability self-report biases. Ratings of neutral words provided us with an indirect, nonobvious measure of SWB.

Procedure

All participants carried out the tasks for this study within the first five weeks of Fall quarter, 1999. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. In the gratitude condition, participants were asked to recall things they did over the previous summer that they felt grateful for. In the second condition participants were asked to list things they wanted to do over the summer but were not able to do. Participants engaged in these tasks for 5 minutes. Following this manipulation participants first completed a five-point Likert type scale indicating how grateful they felt for the summer. Participants then completed the PANAS, followed by the neutral word ratings, the SDFMS, the BDI, the SWLS and the GRAT.

Results And Discussion

We analyzed the impact of our manipulation on positive and negative affect separately with a 2 (gratitude condition) × 2 (gender) ANOVA. There were no significant main effects or interactions involving gender. Although the means were in the predicted direction for both positive and negative affect, gratitude condition showed a significant difference only with negative affect, F(1,100) = 6.21, p < .05, ηp2 = .057 (small to moderate effect size). The gratitude condition showed lower negative affect scores (mean=15.74, SE=1.01), than the control condition (mean = 18.27, SE = 0.96). Thus, in this study it appeared that a simple gratitude priming task was shown to improve mood. Although we found significant differences between the two conditions, it should be stated that it is possible that the control condition produced more negative affect than did the gratitude condition improving mood. In Study 4 we used a more neutral control condition to clarify this ambiguity.

We then conducted correlational analyses with the various measures to further evaluate the construct validity of the GRAT. Table 3 displays these relationships. Again, the GRAT was positively related to measures of SWB, and negatively related to depression. The disposition of gratitude implies that individuals high in this trait should be more likely to experience gratitude. Are grateful people indeed more likely to experience gratitude? Correlations between the GRAT and ratings of gratitude for the summer suggest that they are. However, because we did not evaluate mood prior to our manipulation, this design did not allow us to evaluate whether or not grateful individuals are more likely to experience an increase in positive affect in the context of a gratitude exercise. Also, debriefing interviews of our participants suggested that because we asked them to list asmany things as possible that they were grateful for over the summer, the task of listing might have mitigated their experience of gratitude somewhat. In Study 4, we attempted to design a gratitude manipulation that accounted for these problems.

Study 4

In this study we again sought to investigate whether grateful reflections can enhance positive affect. We were also interested in whether the nature of grateful experience/expression affects the extent of positive affect experienced. Third, we were interested in whether an individual's GRAT score administered before the experimental session would be predictive of his or her response to the gratitude manipulation. Finally, because we also administered the GRAT at the conclusion of the experimental session, this afforded an opportunity to evaluate the temporal stability of the GRAT.

Method

Participants

One hundred and fifty-seven undergraduate students participated in this study and received partial course credit for this activity. One participant was excluded because of failing to complete all the measures.

Materials

We used the PANAS as our primary dependent variable, administered both before and after treatment to evaluate affect changes over the course of the experiment. The PAST (Past Accounts of Sadness Test; Watkins & Curtis, 1994) was administered prior to treatment primarily to distract participants from our primary purpose - that of detecting affect changes. We also administered 8 bipolar affect scales. These scales were administered in an 8-point Likert format, and are listed on Table 4. The primary purpose of these scales was to provide data regarding predictive validity of the GRAT. Following the experimental treatment, all participants completed these affect scales as well as the GRAT.

Procedure

In initial mass-testing sessions participants were administered the GRAT along with a number of other measures not relevant to this study. Students were then contacted to arrange participation in the experiment. Time between mass testing and the experimental session was not less than two weeks but not greater than two months. After signing a consent form participants were administered the PAST, followed by the PANAS and the 8 bipolar affect scales. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of four conditions. In the control condition (n = 38), participants were asked to write about the lay-out of their living room. The remaining participants were randomly assigned to one of three gratitude conditions (thinking, essay, and letter). In the grateful thinking condition (n = 39), participants were instructed to think about someone living for whom they were grateful. As soon as the participant indicated they had thought of the person, timing began and the participant began thinking about this person. In the grateful essay condition (n = 37) participants were asked to write about someone they were grateful for. As soon as the participant began writing the timing began for five minutes. Finally, some participants were engaged in the grateful letter condition (n = 42). In this condition participants were asked to write a letter to a living person for whom they were grateful. Participants were told that the experimenter would not see the letter, but would mail it for the participant. Participants were also told that they would be phoned in about a week to see how the recipient received the letter. Although we did not actually mail the letter (at the conclusion of the experiment we gave them the letter to do with as they pleased), we felt that this cover story would encourage the participants to take the letter-writing task seriously. Following the experimental manipulation all participants were again administered the affect scales, followed by the PANAS, BDI, SDFMS, and concluding with the GRAT.

Results and Discussion

We analyzed the impact of our experimental manipulation by conducting a mixed-factorial General Linear Model (GLM) analysis for positive and negative affect as measured by the PANAS. Time (pretreatment and posttreatment) was our within subjects variable and condition was the between subjects variable. For positive affect, we found a main effect for time, F(1, 152) = 19.70, p < .05, ηp2 = .115 (moderate effect size). Observation of means indicated that this effect was due to posttreatment positive affect scores being higher than pretreatment affect scores. However, this main effect was modified by a significant time × condition interaction, F(3, 152) = 6.84, p < .05, ηp2 = .119 (moderate effect size). As predicted, the gratitude conditions showed reliable increases in positive affect and this was not the case in the control condition. This finding is depicted in Figure 1 using PANAS change scores (posttreatment – pretreatment). Somewhat surprisingly, the grateful thinking condition showed the strongest effect. We expected the letter-writing condition to show the strongest effect because in this condition our participants were engaging in a social expression of gratitude. It is possible that writing about positive events or persons engages cognitive processes that interrupt the experience of positive affect. If this is the case, this

has clear implications for gratitude interventions. However, it could also be that the writing conditions produced more social anxiety than in the grateful thinking condition. Our cover story for the letter-writing condition could have concerned our participants in that they were worried about how their benefactor would receive the letter.

We conducted a similar GLM analysis for negative-affect scores from the PANAS. Again we found a significant main effect for time, F(1, 152) =16.90, p < .05, ηp2 = .100 (moderate effect size). Negative affect reliably decreased from pre to posttreatment. Unlike positive affect, the time x condition interaction did not reach significance, F(3, 152) =1.51, ns, ηp2 = .022. Negative affect decreases were not reliably different across our experimental conditions, although the pattern of the means was in the expected direction.

Finally, we conducted several correlational analyses to further investigate the validity of the GRAT. Because we administered the GRAT at screening and in the experimental session, we were able to evaluate the temporal stability of the GRAT (two weeks to two months). The two administrations correlated highly, demonstrating good test-retest reliability. The full GRAT scores correlated at r = .90, p < .0001. The subscales of the GRAT also correlated highly between the two administrations (Ab r = .87, SA r = .85, AO r = .80).

We also conducted correlation analyses between the screening GRAT and the affect measures administered at pretest. These results are shown in Table 4. Again, in general positive affect correlated positively and negative affect correlated negatively with the GRAT. Of our bipolar affect scales, the highest correlations were between the GRAT and happiness, thankfulness, and contentment. These results provide further support for the construct validity of the GRAT. Of particular note, the GRAT reliably predicted future feelings of thankfulness, as would be expected of an affective trait measure. Again, sadness was more strongly associated with the GRAT than was fear, and the correlation coefficients were significantly different (z = 2.49, p < .01).

Our design also allowed us to conduct correlational analyses to evaluate whether GRAT scores predicted affect changes in the gratitude experimental conditions. Thus, we correlated screening GRAT scores with affect changes in the three gratitude conditions. Difference scores on the PANAS were computed by subtracting the pretreatment scores from the posttreatment scores. Screening GRAT scores reliably predicted increases in positive affect (r = .22, p < .05), but did not predict positive affect changes in the control condition. Changes in negative affect were not significantly related to screening GRAT scores. These results suggest that grateful individuals are more likely to enjoy gratitude exercises. As discussed above, screening GRAT scores were significantly and positively associated with pretreatment positive affect scores. Thus, grateful individuals had less room for improvement in positive affect, but still showed greater increases of positive affect than did less grateful individuals. We believe that this was a particularly strong test of the criterion-related validity of the GRAT. In sum, this study showed that gratitude exercises reliably cause increases in positive affect, and that grateful individuals show stronger increases than do their less grateful counterparts.

General Discussion

In this series of studies we sought to develop a psychometrically sound measure of trait gratitude, and to evaluate the relationship between gratitude and SWB. Our results suggest that the GRAT is a reliable and valid measure of dispositional gratitude. Results also suggest that grateful individuals tend to be happy and well adjusted.

In two studies, we found that the GRAT contains excellent internal consistency and temporal stability. We also found good support for the construct validity of this measure, in that it was predictive of grateful feelings in the future, and correlated in the expected manner with a number of relevant variables. Of course, the GRAT suffers from the same weaknesses as other self-report measures. Most notably, scores on the GRAT are probably somewhat reflective of a positivity bias. However, we do not believe this to be a significant weakness because a positively biased approach to life is also likely to be an important characteristic of the grateful person.

We also found strong relationships between dispositional gratitude and various measures of happiness and SWB. While most of these associations were demonstrated with direct self-report measures, in Study 3 we showed that gratitude was also correlated with an indirect measure of happiness (semantic differential ratings of neutral words). The association of the GRAT with the SWLS compares quite favorably with other personality traits that have been shown to have reliable associations with SWB (see Watkins, in press). Of course, these correlations may simply reflect the idea that gratitude is an epiphenomenon of happiness. However, in two studies we found that gratitude interventions improved mood. In a more long-term investigation on the impact of gratitude on emotional well-being, Emmons and McCullough (2003) found similar effects. In three studies, they demonstrated that a daily and weekly practice of gratitude caused increases in a number of positive affect variables, including SWB and hope. Their gratitude intervention also prompted decreases in a number of negative affect variables. Because the field of SWB has largely relied on correlational designs, results indicating that the induction of grateful thoughts can actually cause improvements in SWB are of particular significance.

How does gratitude promote SWB? The answer to this question awaits future research, but some authors have offered suggestions as to how gratitude might enhance SWB (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Watkins, in press). For example, gratitude might promote happiness by enhancing one's experience of positive events, by enhancing adaptive coping to negative events, by enhancing encoding and retrieval of positive events, by enhancing one's social network, or by preventing or mitigating depression. Investigations into these proposed mechanisms should provide valuable information for the understanding of happiness.

Although we have demonstrated that gratitude can cause positive affect, it is still possible that happiness enhances gratitude as well. Positive affect research provides a number of reasons why gratitude should be more likely in the presence of positive affect (see Isen, 1999). Does the relationship between gratitude and SWB result from gratitude causing happiness, or is it that happiness causes gratitude? In answer to this conundrum we support the notion that happiness and gratitude may operate in a "cycle of virtue" (Watkins, in press), whereby gratitude enhances happiness, but happiness enhances gratitude as well. This may be another "upward spiral" where positive affect has been proposed to provide benefits for the individual that tend to feed into further benefits (cf. Fredrickson, 1998). Clearly, these speculative notions await further research.

We have argued that there are several components to trait gratitude. In large measure, our results support the notion that grateful individuals have at least three characteristics. First, grateful individuals have a sense of abundance. Grateful individuals do not feel that they have been deprived in life. The second component of trait gratitude appears to be an appreciation of simple pleasures. Our results suggest that grateful individuals appreciate the common everyday pleasures of life. Thirdly, grateful individuals appreciate the contribution of others to their well-being. While our locus-of-control findings suggest that grateful individuals still take appropriate credit for their successes, our results also imply that grateful individuals are quick to acknowledge how others have contributed to their well-being. Results from our religiosity measures suggest that not only do grateful individuals admit the beneficial contributions of their fellow humans, they are also more likely to acknowledge the contribution of the divine.

Is there a grateful trait? Taken together, the results presented here and elsewhere (McCullough et al., 2002), indicate that there is a grateful trait, that it can be reliably measured, and that it is strongly associated with SWB. Because positive emotions are less studied than negative states and traits (Fredrickson, 1998), investigations into traits relating to positive affect are needed. We have found that grateful individuals tend to be happy individuals, and that grateful thinking improves mood. Although the science of gratitude is still in its infancy, preliminary findings suggest that gratitude may be an important component of the good life.

References

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and religious prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432-443.

Bar-Tal, D., Bar-Zohar, Y., Greenberg, M. S., & Hermon, M. (1977). Reciprocity behavior in the relationship between donor and recipient and between harm-doer and victim. Sociometry, 40, 293-298.

Beck, A. T. (1972). Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Berrenberg, J. L. (1987). The Belief in Personal Control Scale: A measure of God-mediated and exaggerated control. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51, 194-206.

Brugha, T. S., & Cragg, D. (1990). The list of threatening experiences: The reliability and validity of a brief Life Events Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 82, 77-81.

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452-459.

Chesterton, G. K. (1986). Orthodoxy, in G. K. Chesterton: Collected works, San Francisco: Ignatius Press. Original work published in 1908.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276-302.

Dumas, J. E., Johnson, M., & Lynch, A. M. (2002). Likableness, familiarity, and frequency of 844 person-descriptive words. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 523-531.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (2000). Gratitude as human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 849-857.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377-389.

Fordyce, M. W. (1988). A review of research on the Happiness Measures: A sixty second index of happiness and mental health. Social Indicators Research, 20, 355-381.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300-319.

Gallup, G. (1998). Gallup survey results on "gratitude", adults and teenagers. Emerging Trends, 20 (4-5), 9.

Guralnik, D. B. (1971). Webster's New World dictionary. Nashville, TN: Southwestern Co.

Isen, A. M. (1999). Positive affect. In T. Dalgleish and M. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion. New York: John Wiley, pp. 521-539.

Kuykendall, D., Keating, J. P., & Wagaman, J. (1988). Assessing affective states: A new methodology for some old problems. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 12, 279-294.

Lewis, C. S. (1958). Reflections on the Psalms. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Lorr, M., & Wunderlich, R. A. (1988). A Semantic Differential Mood Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 33-35.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112-127.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127, 249-266.

Myers, D., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy? Psychological Science, 6, 10-18.

Phares, E. J., & Erskine, N. (1984). The measurement of selfism. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 44, 597-608.

Rosenberg, E. L. (1998). Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Review of General Psychology, 2, 247-270.

Watkins, P. C. (2001). Gratitude: The benefits of an emotional state and trait. Spirituality and Medicine Connection, 5(1), 6-7.

Watkins, P. C. (in press). Gratitude and subjective well-being. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude. New York: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, P. C., & Curtis, N. (1994, April). Brief assessment of depression history. Presentation to the 74th Annual Convention of the Western Psychological Association, Kona, HI.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92, 548-573.

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and religious prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432-443.

Bar-Tal, D., Bar-Zohar, Y., Greenberg, M. S., & Hermon, M. (1977). Reciprocity behavior in the relationship between donor and recipient and between harm-doer and victim. Sociometry, 40, 293-298.

Beck, A. T. (1972). Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Berrenberg, J. L. (1987). The Belief in Personal Control Scale: A measure of God-mediated and exaggerated control. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51, 194-206.

Brugha, T. S., & Cragg, D. (1990). The list of threatening experiences: The reliability and validity of a brief Life Events Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 82, 77-81.

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452-459.

Chesterton, G. K. (1986). Orthodoxy, in G. K. Chesterton: Collected works, San Francisco: Ignatius Press. Original work published in 1908.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276-302.

Dumas, J. E., Johnson, M., & Lynch, A. M. (2002). Likableness, familiarity, and frequency of 844 person-descriptive words. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 523-531.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (2000). Gratitude as human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 849-857.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377-389.

Fordyce, M. W. (1988). A review of research on the Happiness Measures: A sixty second index of happiness and mental health. Social Indicators Research, 20, 355-381.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300-319.

Gallup, G. (1998). Gallup survey results on "gratitude", adults and teenagers. Emerging Trends, 20 (4-5), 9.

Guralnik, D. B. (1971). Webster's New World dictionary. Nashville, TN: Southwestern Co.

Isen, A. M. (1999). Positive affect. In T. Dalgleish and M. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion. New York: John Wiley, pp. 521-539.

Kuykendall, D., Keating, J. P., & Wagaman, J. (1988). Assessing affective states: A new methodology for some old problems. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 12, 279-294.

Lewis, C. S. (1958). Reflections on the Psalms. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Lorr, M., & Wunderlich, R. A. (1988). A Semantic Differential Mood Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 33-35.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112-127.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127, 249-266.

Myers, D., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy? Psychological Science, 6, 10-18.

Phares, E. J., & Erskine, N. (1984). The measurement of selfism. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 44, 597-608.

Rosenberg, E. L. (1998). Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Review of General Psychology, 2, 247-270.

Watkins, P. C. (2001). Gratitude: The benefits of an emotional state and trait. Spirituality and Medicine Connection, 5(1), 6-7.

Watkins, P. C. (in press). Gratitude and subjective well-being. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude. New York: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, P. C., & Curtis, N. (1994, April). Brief assessment of depression history. Presentation to the 74th Annual Convention of the Western Psychological Association, Kona, HI.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92, 548-573.

* Indicates item is reverse scored. Ab=Sense of Abundance, SA=Simple Appreciation, AO=Appreciation for Others.

This paper was supported in part by a generous grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The authors wish to dedicate this paper to the memory of Nick Curtis.

Appreciation is due to reviewers including Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

PhD

Director

Quality of Life Research Center

C. S. and D. J. Davidson

Professor

Peter F. Drucker School of Management

Claremont Graduate University

1021 N. Dartmouth Avenue

Claremont

CA 91711

USA. Email

Michael E. McCullough

Associate Professor

Department of Psychology and Department of Religious Studies

University of Miami

P.O. Box 248185

Coral Gables

FL 33124-2070

[email protected]">[email protected]

http

//www.psy.miami.edu/ faculty/mmccullough/index.html.